Even the most incorrigible dreamers and idealists (in both the philosophical and quotidian senses of the word) among us believe that they are realists in at least the pragmatic sense. That is to say, most of us most of the time act upon our world as though the objects in it had a reality independent of our own minds. We have projects and goals, of course; that is, we “project” onto reality the things we wish to make manifest within it, but we insist that we recognize the distinction between such hopeful projection and the world as it now stands.

Our dreams are not fulfilled until such time that they cross over from being mere projections into a materialized real presence. Our awareness of the difference between fantasy and reality is meant to be the mark of sanity.

And yet, one of the key psychological insights into human existence (known long before Freud and modern psychoanalysis) is that we are quite mistaken in our belief that we occupy a mind-independent reality. The world stands for me not as it “really is” but rather as it appears to me within the framework of my aspirations, my fears, my loves, and my hatreds. Martin Heidegger employs the term “Mood” (Stimmung) to account for this disposition toward having the world “show up” for us in a certain way.

The word Stimmung also means “tuning” — a compelling and revealing etymological connection. Insofar as I have a mood, I am tuned in such a way that the world resonates with me in a characteristic manner. Think of sympathetic vibration in an instrument. If I have a string tuned to A110 on a guitar and I loudly hit the piano key of A110, that guitar string will vibrate without having been directly struck. But if that string is out of tune (I suppose, to be accurate, I should write that it is “differently tuned”), then it will not sympathetically vibrate with the piano.

Returning to the issue of mood, we can see how this notion connects with ideas about emotional sympathy. To be sympathetic here is to have something “resonate” with you — not to experience it directly but to be open to being moved (vibrated, if you will) indirectly. When I feel sympathy toward a homeless woman, it is not that I believe I can know exactly what deprivations that woman has suffered, but that I am able to be moved by her plight.

Being open to the world through mood is what Heidegger calls Befindlichkeit, sometimes translated as “attunement” (in line with the etymology of Stimmung). “Attunement” is emphatically not a state of mind, it is pre-cognitive and even pre-subjective. That is to say, my cognitions and sense of subjecthood depend upon mood, not the other way around. As an example, if I say I am in a foul mood owing to something you have done, something that I take amiss, I am not using the term “mood” in the Heideggerian sense. In this example, I am using mood for something that is cognitive and subjective — it’s a response to something that has occurred in my life, an entanglement with what is. Heideggerian Stimmung, on the other hand, addresses the condition of the possibility of my having any reactions at all. Mood, in this sense, involves not what is but rather a set of possibilities; it sets out the space for what can be.

So, for Heidegger, Stimmung isn’t my current surface mood that colors how I see the world today, it is a deeper, more protracted manner of my being that allows for the world to “show up” to me in the manner that it does. Mood, for Heidegger, is inextricably bound up with two other existential conditions of human existence: Understanding (Verstehen) and Discourse (Rede). Both of these conditions are also pre-cognitive and pre-subjective.

Understanding indicates the manner in which I am disposed toward my projects. Most of these projects are not thought-out and explicit. For example, insofar as I see myself as a good son to my mother, I do things that contribute to that manner of being. So, when I find myself in a drugstore in early July, the birthday cards on sale appeal to my Understanding as something that supports that project. I don’t necessarily try consciously to be a good son (it is not only my New Year’s resolution list); it is part of what it means to be the person that I am. And yet, being a good son is not merely a given — it is a project in that it involves continuous action (much of it pre-cognitive).

That manner of being a good son, or whatever other social roles I fulfill, was not invented by me out of whole cloth; it is not some kind of personal goal or decision. It is a social role. It pre-existed me. The kind of moods available to me and the kind of projects I pursue are at least partially conditioned by the ways in which such moods and projects are circulated by the society in which I am immersed. The term “immersion” is, of course, deliberate here. Heidegger’s aim is not to depict the self as some regent that gazes upon the world from a removed distance. We are utterly involved in the world. We don’t generally observe it as such (except in relatively rare cases); we act within it and upon it as it acts upon us.

Mood, Understanding, and Discourse, therefore, are not things that we do; they are the pre-cognitive and pre-subjective grounds of the possibility of our doing anything, indeed, of our ability to see that there is anything worth doing. But notice that all three of these existential components of human being-in-the-world involve not simply what is “out there” in reality, but rather they constitute the possibility of our making sense of the world. Owing to their influence, the world reveals itself as a certain kind of place, with a certain set of meanings and possibilities. Simply put, our involvement in the world is as much projection and fantasy as it is dealing with brute fact and reality.

Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu plunges the viewer into a worldview that witnesses the nearly indiscriminate imbrication of reality and fantasy. Mizoguchi insisted that he wanted these realms to be indistinguishable insofar as possible within the film. Ugetsu examines the lives of two couples during the period of civil war and social upheaval. Genjuro (Masayuki Mori) is a potter, eager to take advantage of the current state of unrest in order to turn a profit. His wife, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka), seeks some modicum of stability within the turmoil that surrounds them. Fearing for the safety of her husband, Miyagi implores Genjuro not to risk the journey into town for the sake of mere wealth.

Tobei (Sakae Ozawa), Genjuro’s brother who lives on a neighboring farm, has the rather far-flung (for someone of his social station) ambition to be a revered samurai. His wife, Ohama (Mitsuko Mito), harangues him about the impracticality of such an all-consuming dream, encouraging him to turn his efforts toward his agricultural occupation.

Notice the way in which these alternate ways of viewing the world, inflicted through culturally sanctioned gender norms, are bound up in Heidegger’s triune categories of Mood, Understanding, and Discourse. The men are inclined (through Mood) toward outsized aspiration. They seek recognition and renown. Genjuro desires safety and comfort for his family; this is touchingly portrayed in any scene where Genjuro insists Miyagi return home to avoid sharing the risks he faces (he repeatedly urges her to take the longer but safer route home). He is, however, willing to leverage a certain amount of danger now for the possibility of greater future prosperity and security. Thus, he assesses (through Understanding) the situation for the possibilities that holds for his projects. Moreover, the ambitions of his (and even the more ludicrous ambitions that Tobei holds dear) are not idiosyncratic or entirely personal. They come to him, in part, through contemporaneous social expectations (that is, Discourse) regarding men in their obligation not only to provide for their families put to extend their sense of vitality, to exert and spend themselves in their attempts at recognition and social standing.

The women, likewise, see a set of possibilities for living in the world that are also not entirely realistic and equally predicated upon Heidegger’s three categories, as well as traditional gender roles. Their vision (Mood) a familiar bless insecurity cannot be realized without some concession to “male” ambition. Their seeming good sense (and we are clearly meant to see Miyagi as being in the right) is tempered by a slippery faith that togetherness vouchsafes security. This abiding trust in the blessedness of the familial derives from their Understanding in relation to their projects — but their practicality is ultimately impractical, grounded in the Discourse of the traditional view of woman as guarantor of familial cohesion.

Mizoguchi is widely celebrated for his focus on, and sympathy for, the lives of women. His films often document the suffering of women that is seemingly an intrinsic part of postwar Japan and the historical eras he chose as its surrogates. Ugetsu reverberates with Mizoguchi’s familiar concerns. Abandoned by their husbands, both Miyagi and Ohama must endure degradation, stark isolation, and the cruel violence of strange men.

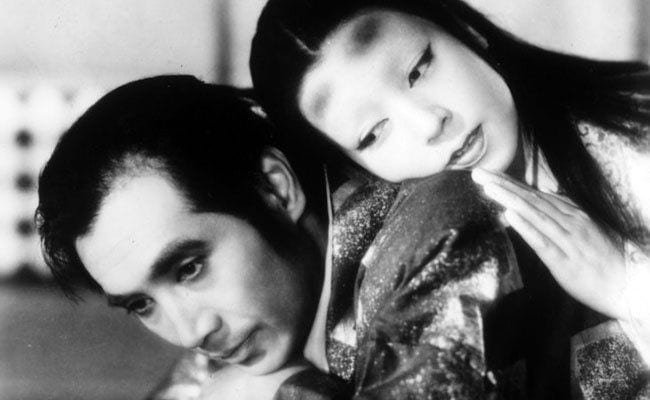

But there is another aspect of Ugetsu that strongly contrasts with Mizoguchi’s typical approach to film. This narrative concentrates far more on the fate and psychological condition and development of Genjuro, the male protagonist. If Mizoguchi intended the film to explore the proximity of the real and the fantastic, then it is within Genjuro’s experience that this proximity is felt. No other major character interacts with ghosts. Genjuro abandons his wife to her fate, and remains in town when he is seduced by Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyo), a specter haunting her old residence.

Mizoguchi’s handling of the supernatural here is remarkable. When Genjuro accompanies Lady Wakasa to Kutsuki mansion for the first time, the outskirts of the home are clearly in ruins. As Genjuro moves further into the residence it gradually takes on a refined splendor and appears to be in pristine condition. There is no transformation that unfolds before our eyes in Hollywood fashion. Rather, as Genjuro further penetrates into the mansion and into his ties to Lady Wakasa, he increasingly invests himself in his own delusion.

Wakasa represents all of the things that Genjuro believes he deserves — the markers of the end point of his artistic projects. She recognizes him as a great artist, offers him a sense of social importance, and provides him with sensual gratification. In an earlier scene, Genjuro had bought Miyagi a fine kimono. She appreciated the gift more for his attention than the finery of the fabric. With Wakasa, Genjuro has someone that can appreciate aesthetic refinement the way he feels he does. Mizoguchi implies that we are not so much haunted by ghosts as we project our own specters upon our reality, inhabiting the world with illusions of our own making. It is a dark take on Heidegger’s notions of Mood and Understanding.

The film garners an even darker insight when Genjuro finally returns home seeking Miyagi. He finds her at the hearth awaiting him. He sleeps deeply, the rest of relief, only to awake to find that Miyagi died years ago and he had encountered yet another ghost, another projection. In a voiceover, Miyagi claims that Genjuro had finally become the man she had always wanted him to be. This, I fear, is the melancholy revelation awaiting many of us when we deeply ponder the notion of love.

Jacque Lacan famously quipped “There is no sexual relationship”, by which he meant (at least in part) that we don’t have a relationship directly with the one we love, but rather with our fantasy projection of that loved one. In this sense, Miyagi is not the only specter haunting their marriage. Genjuro was as well. She projected a fantasy onto him, the vision of the man she wished she had married or believed he could become given time enough and love. But such changes always seem to come too late. We suffer for what we ought to be while trying so hard to fulfill the image of what we wish we were.

We are wholly independent, with no corporate backers.

Simply whitelisting PopMatters is a show of support.

Thank you.

Criterion Collection has recently released a Blu-ray edition of this celebrated film in a deluxe package that includes a fine audio commentary by Tony Rayns; an in-depth documentary on Mizoguchi (Kenji Mizoguchi: The Life of a Film Director) from 1975 by filmmaker (and Mizoguchi protégé) Kaneto Shindo (regarded in some circles as the finest documentary ever made on a film director); interviews with Tokuzo Tanaka (the first assistant director of the film) and cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa; and an appreciation of the film by Masahiro Shinoda. The interview with Tanaka is particularly compelling and provides a keen insight into film production and its vicissitudes in post-war Japan.

The booklet that accompanies the disc is a major work in its own right. It contains a penetrating essay by Phillip Lopate, and translations of the three short stories that inspired the film: two by Akinari Ueda and one by Guy de Maupassant, whom Mizoguchi read in a very popular Japanese translation and which informed the Tobei/Ohama portions of the film.