“The Red Parts,” for those unfamiliar with the term (as I was), are those (very few) parts of the Bible in which Jesus speaks, those which Christians believe to be the most vital, momentous, meaningful passages. The title of Maggie Nelson’s book includes this meaning of the phrase, but, more obviously, refers to the “red parts” of our bodies — our insides, our flesh, our genitals, our guts, our “nasty bits.”

The “red parts” in question are those of Maggie Nelson’s Aunt Jane, a woman she never knew, who died before she was born, at the age of 23. Smart, studious Jane Louise Mixer was one of a small number of female law students at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor in March 1969 when she was on her way home to tell her parents she was getting married. The last thing she did was to arrange for a ride through the campus bulletin board. The following day, her body was found about 14 miles from campus in a cemetery. She’d been shot twice in the head and strangled. Six other young women were murdered around the same time, and police assumed they’d all been victims of the “Michigan Murderer” John Collins, who was convicted shortly afterwards.

These facts provided the basis of Maggie Nelson’s earlier book on her aunt’s case, Jane: A Murder (Soft Skull Press, 2005), which really works as the companion piece to The Red Parts (I read them consecutively, one after the other, unable to stop). Jane is hard to classify. Nelson refers to it as a book of poetry, which it is, but it’s also a collection of memories, diary entries, conversations, dreams, fantasies, and facts.

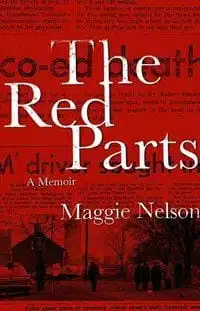

Coincidentally, just as Jane was about to be published in 2004, a DNA match led to the arrest of a new suspect for Jane’s murder. This re-opening of a case long assumed to be closed, and the new suspect’s trial and conviction, forms the meat of The Red Parts.

Nelson has commented in interviews that she spent years working on Jane, and contrast to the thoughtful, poignant tone of the earlier book, The Red Parts feels rushed, frenzied — in a positive, powerful way. While the re-opening of Jane’s case provides a plot, the book is also an autopsy, an examination (both implicit and explicit) on our cultural fascination with voyeurism, death, sex, and misogyny. Instead of distancing herself from these subjects, Nelson is fascinated by them, and acknowledges her complicity, her inability to escape from certain habits of thought, whether these be “murder mind,” “suicide mind,” or more everyday (though no less traumatic) ruts — her problems dealing with a junkie boyfriend, abandonment by her lover, getting along with her extended mother and extended family during the long process of the trial.

In sum, The Red Parts is a tour de force for anyone with the slightest interest in true crime.