The splendor of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) was long preceded by a tentative TV courtship. Creative failures by today’s standards, the Marvel-based television of the ’70s lingers in the forgiving memories of a generation, while also speaking to the limitations of capitalism in exploiting changing tastes. In addition to CGI, today’s Hollywood finally has a savvy confidence in superheroes as mass entertainment.

Despite their association with childhood, the superhero narrative is a strong stew: violent vigilantism, obsession and psychological arrest, kinky costumes, and rampant sublimation. It’s clear that 20th-century Hollywood was leery: DC’s superheroes came to television laced with camp (especially Batman), a quality skirted by the Tim Burton films, which trailed a decade behind Christopher Reeve’s turn as Superman, film that themselves were produced by the non-Hollywood Salkind family.

Still, the sci-fi boom and high-profile approach of Superman (1978) stirred the market, and Universal bought the rights to various Marvel characters, ultimately producing live-action Spider-Man and Hulk series, as well as pilots for Captain America and Dr. Strange (all for CBS). Today, these films and series are considered camp, and provide mainly nostalgia, but even at the time, fans complained of dull plots, altered costumes, and other infidelities. On The Incredible Hulk, Bruce Banner’s first name became David, and the Hulk doesn’t talk (not even a “Hulk Smash”). The known supervillains of the comic books were replaced by TV’s usual crooks and terrorists, even if they happened to be armed with futuristic tools, such as dis-inhibiting gas or cloning technology.

The harshest reviews land on a pair of 1979 Captain America TV movies (both on DVD), with beefy Reb Brown as the titular hero. Captain America, a poor fit for the post-Vietnam era, has his origin story changed; he’s now a present-day artist and wears a motorcycle helmet (maybe to discourage kids from getting ideas about the fast-healing promised by the narrative’s super-steroid). Contracts called for eight Marvel-based TV-movies, so there’s a sequel, with the self-mocking title Captain America: Death Too Soon, and boasting Christopher Lee as a guest star. Lee would’ve made a great Red Skull, but alas, he’s not playing Red Skull; instead, in questionable casting decision, Lee plays a revolutionary named Miguel.

Producers also sniffed around The Human Torch and Sub-Mariner; the latter may have sunk with The Man From Atlantis, NBC’s lawyer-bait rip of the oceanic exemplar (starring a pre-Dallas Patrick Duffy). Instead, viewers got Dr. Strange (1978, on DVD), a pilot-movie by Phil DeGuere, who’d later shepherd the rebooted Twilight Zone of the ’80s, as well as creating the more commercial series Simon and Simon. With its horror and fantasy roots, Dr. Strange was closer to TV’s wheelhouse; it was also the sort of series that drew complaints from the Bible Belt, but low ratings apparently made that moot. The solid cast strikes a balance of awe vs. camp: Peter Hooten, Jessica Walter (Lucille Bluth in Arrested Development), and Anne-Marie Martin (later Dori Doreau of the cult spoof-com Sledge Hammer!).

While I’m focusing on live-action series, it’s worth noting that in terms of pre-MCU adaptations, comic buffs favor animation, especially a cycle of cartoon series from the ’90s. Reaching back to 1967, close to the originators, ABC debuted the well-remembered Fantastic Four and Spider-Man cartoons, of which the latter can claim the immortally catchy Spider-Man theme song. This theme is missing from the 1977 to 1979 live-action show, which is unfortunate: the score for The Amazing Spider-Man is more criminal than any of its villains.

In retrospect, adapting Spider-Man is nearly impossible in pre-CGI live-action. The 1977 pilot movie does a surprisingly adequate job, but thereafter, the show makes much of Spidey walking treacherous heights (eg, construction beams) and soft-landing on a ceiling or wall. Nicholas Hammond makes an adequate Peter Parker, even if he’s clearly older than his ingenious character. Unfortunately, ’70s TV was so skittish it deletes Uncle Ben entirely, thus missing one of the main points of Parker’s characterization. The entire production is tentative and stiff, built on bland, vaguely reactionary storylines.

Nevertheless, in Epi-log Journal #14 (Spring 1994), a before-its-time publication consisting mostly of episode guides, Craig W. Frey, Jr. recalled the childhood excitement of seeing Spider-Man in primetime, however hamstrung were the plots and production. Frey prefers the sleek costume of the pilot (gauntlets and a belt were added later), but gives highest marks to “The Chinese Web” (a two-part episode) and “The Captive Tower”.

“The Captive Tower” actually anticipates both Die Hard and The Rock in story terms, with an office tower seized by a gang of a bitter Vietnam veterans. David Sheiner as Forster is a tough villain, but the show is too bright and safe to work, and there’s wince-inducing comic relief about a nebbish crook in love with the building’s security computer. In fact, IMDb voters prefer “The Wolfpack”, the story of citizens brainwashed into crime, and it tracks a little better, benefiting from the presence of TV veteran Allan Arbus.

Even Stan Lee, the famously positive Marvel patriarch, has no use for this series: “Terrible. They lost all of the personality … no dimension to it, no depth” (Television Chronicles #10, July 1997). The Amazing Spider-Man is passively suppressed, with bad prints viewable on YouTube as of this writing. A bolder strategy would be to repurpose this content inside a postmodern frame, as the sanitized version of the hero’s exploits. Hammond, after all, is still acting, although he’d likely want plane fare from his adopted home of Australia.

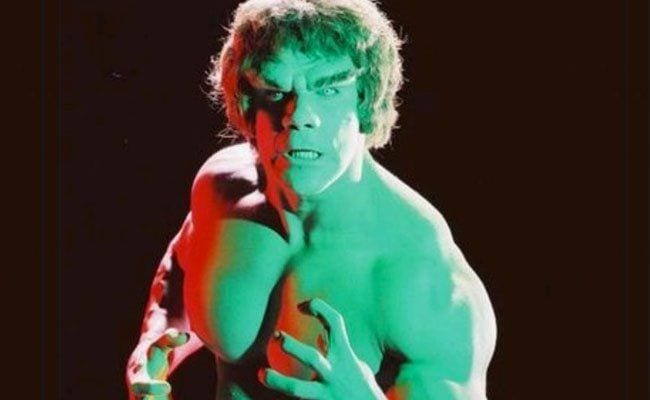

If the ’70s-era Amazing Spider-Man never found an identity, it’s partly because CBS took almost two years to air the 14 episodes as occasional filler. As the network committed to The Incredible Hulk, Spidey’s fate was sealed, since it was unlikely, at least back then, that a major network would’ve hosted multiple comic book/superhero shows. (Currently, the CW network runs five: Arrow, The Flash, Supergirl, Legends of Tomorrow, and iZombie.) On the opposite end of the spectrum, The Incredible Hulk (1978-82, available streaming or on DVD, as are the three follow-up TV movies) hit the right formula for superheroes on TV: lush, seductive visuals (easier on CBS, then known as the Tiffany network), and a protagonist who’s almost as amazed by his powers as the viewers. It’s the nature of the Hulk that he may never graduate from apprentice superhero, so despite two Hulk-outs per episode, the CBS series is spiritual forerunner to coming-of-age prequels such as the CW’s Smallville.

The Incredible Hulk was classified a hit, but it’s complicated: its 82 hour-long episodes (over five seasons) are only three more than Star Trek, the latter a famously a first-run flop. Aired on CBS, The Incredible Hulk‘s five seasons are really three-and-a-half, plus delays. Still, it ran on a dominant network and on the notoriously difficult Friday night. While Fridays can be a haven for kid-appeal shows, such as The Man From U.N.C.L.E., The Wild Wild West, and ABC’s ’90s-era TGIF sitcoms, it often spells death for drama; just ask Joss Whedon.

As with ABC’s bionic heroes, parents trusted the Hulk to babysit. The format fits all ages: the Hulk is green, childlike, and protective of Banner’s friends, whereas Banner’s an otherwise normal, intelligent man (the show implies that unlike some versions of the character, David Banner can have sex). The casting was also age-inclusive: Bill Bixby was 44 when the series began, bodybuilder Lou Ferrigno was 26, and child actors made frequent appearances.

We are wholly independent, with no corporate backers.

Simply whitelisting PopMatters is a show of support.

Thank you.

The Incredible Hulk followed the lead of The Six Million Dollar Man (1974-78) in starting as multiple TV movies, and in using restraint with fantasy elements: this Hulk can’t make the vast leaps or “thunderclap” of the comic book Hulk, and the series avoids Marvel crossovers, although the follow-up TV movies use Thor [Eric Kramer] and Daredevil [Rex Smith]). Even given limited special effects this seems a missed opportunity, as the era’s TV was so much like comic books to begin with, in its populism and dependence on oversized personae (Fonzie [Henry Winkler] on Happy Days, bald detective Kojak [Telly Savalas]).

Having created The Bionic Woman, showrunner Kenneth Johnson surrendered to typecasting by taking the helm on The Incredible Hulk. Versed in the classics (he attended what’s now Carnegie-Mellon University), Johnson cultivated the story’s echoes of Jekyll and Hyde, and took pages from Les Miserables via The Fugitive by giving Banner an obsessed pursuer, tabloid reporter Jack McGee (Jack Colvin). Banner’s arc turns gothic when his wife dies in a car accident; guilt drives him to obsessive research into super-strength and, one accidental mega-dose of gamma rays later, he Hulks for the very first time.

Whether bionic or Marvel-based, the reluctant-superhero shows rarely surpass the low expectations of the era (add a half-star if you’re a comic book fan, unlike this reviewer, and/or need family viewing). The Incredible Hulk sticks to simple, clichéd plots: the heiress being slowly poisoned, the greedy developer victimizing farmers, the mad scientist experimenting on unwilling subjects. The writers didn’t lack talent: Johnson later produced the solid Alien Nation series (1989-90); Richard Matheson (who wrote three episodes) was a respected prose author, and wrote for both the Serling-era Twilight Zone and Masters of Horror; and both Andrew Schneider (nine episodes) and Diane Frolov (two episodes) later wrote for Northern Exposure, The Sopranos and Boardwalk Empire.

Superheroes, Restrained

They were, however, stuck within the narrow restrictions of network television in the ’70s, such as:

The hero is always heroic. The unintentional result here is to render Banner a busybody. A physician in his former life, he’s not even diplomatic about his interference. Then again, why shouldn’t he play know-it-all when the Hulk is lurking to protect him?

TV should teach moral lessons but never offend anyone. A corollary to the first rule, this is deadly to drama: in a sitcom, you can at least have an Archie Bunker (Carroll O’Connor, All in the Family) or a Ted Baxter (Ted Knight, The Mary Tyler Moore Show), as long as the joke’s on him, but on The Incredible Hulk, the morality is so simplistic, it’s painful (or laughable). Banner never does wrong, and the Hulk acts instinctively, so the central character never faces real moral decisions. This construction breeds hypocrisy, as in “Killer Instinct”, which offers performance-enhanced football violence with a frown.

Every episode ends by resetting the series. At the time, the vast majority of viewers didn’t watch every episode of a series, so Hollywood TV avoided serialized elements (this nervousness survives in shows that begin with “previously on” recaps). Every Incredible Hulk episode ends with Banner walking out of town to the pathetic strains of Joe Harnell’s “The Lonely Man”.

If you must do sci-fi, stick to mad scientists and their creations. Hammer remade the Universal monsters in the ’60s; in the ’70s, it was US television’s turn (on the Universal backlot, no less). As with other media, TV embraced the myth of the cyclic character, with versions of Jekyll and Hyde (Jack Palance, Kirk Douglas), Mr. Spock’s (Leonard Nimoy) pon farr, or Gemini Man, who can stay invisible for only 15 minutes.]

That being said, the fan-favorite Incredible Hulk episodes include the sturdy pilot movie, the most-dangerous-game riff “The Snare”, and several in which the Hulk flirts with evil, including “The Beast Within” and “Dark Side”. Fans also remember the high-concept two-parters “The First” (Hulk vs. his evil counterpart) and “Prometheus” (Hulk captured for military research); neither holds up, although they’d make good remake fodder. A revived series could explore motivations: should David be “cured”? Does he really want a cure? Perhaps he’d rather research time-travel, now that he has the strength to save his wife. David’s loves have a high mortality rate; is he literally cursed?

The cast roster remains the show’s enduring quality. Cameron Mitchell carries the moody noir homage “Goodbye, Eddie Cain”. In “Interview with the Hulk”, reporter Michael Conrad vies with McGee and commiserates with Banner. Sally Kirkland plays the abused mother of an abused child in the still impressive “A Child in Need”. Despite portraying the violent father as merely sick (Banner: “he’s not a criminal”), the show implicitly admits that in the anonymous suburbs, this family needs a miracle (like the Hulk).

Bixby is also reunited with past co-stars in “747” (Brandon Cruz of The Courtship of Eddie’s Father) and “My Favorite Magician” (Ray Walston of My Favorite Martian). “Kindred Spirits” features a young Kim Cattrall, still a little nervous on-screen. Gerald McRaney is fine in the atmospheric “Deathmask”, but filming a slasher movie for family hour caused network anxiety; the episode tips its hand in the first scenes. Mackenzie Phillips is compelling as a troubled rocker in the otherwise-ridiculous “Metamorphosis”. Television rock bands generally had limited repertoires: Lisa Swan and band launch into their “Necktie Nightmare” in three different scenes (“He’s a walking stucco wall, he’s the shadow beneath your sink”).

As an American gothic, The Incredible Hulk loved ill-fated romances, including Susan Sullivan (the pilot film), Mariette Hartley (the two-hour “Married”), Kathryn Leigh Scott of Dark Shadows (“A Solitary Place”), and Andrea Marcovicci (“Triangle”). Typically, Banner meets a female scientist whose research overlaps his own. They fall in love and share fantasies of a cure and life together, but given that rule about resetting the narrative, she’ll be lucky to get out alive.

Lou Ferrigno’s Incredible Hulk always seems confused

Bixby’s turn on My Favorite Martian (1963-66) was an early indication that he had the essential quality of a sci-fi lead: a credible fascination for the incredible. In addition to the obvious examples, this fraternity includes James Mason, Robert Culp, Louise Fletcher, Jodie Foster, Joe Morton, Jennifer Connolly, and Angela Bassett. Throughout the decades, reviewers would praise the show’s “intelligence” and “adult themes”, but they were responding partly to the innate goodness of both leads: Bixby and Ferrigno managed to ground a show featuring sudden cameos by a green, half-naked bodybuilder in bushy wig and eyebrows (and due to restrictions on TV violence, the Hulk mostly strikes poses and smashes props). The two became heroes to a generation: sci-fi royalty. When Hollywood needed to make up for Ang Lee’s sulky Hulk (2003), they stuck closer to the TV series for The Incredible Hulk (2008) with Edward Norton, who earlier met his aggressive alter ego in Fincher’s Fight Club).

Like Wonder Woman, the Hulk has been tough-to-package for the current superhero rally (Banner’s been played by three actors in this century: Eric Bana, Norton, and Mark Ruffalo). Maybe it’s because both superheroes critique society as they protect it, challenging the image of heroes as white-male-rational: if the Hulk is good, it’s because he shares Banner’s good heart.

Marvel’s neurotic mutants demanded a deft treatment that ’70s primetime television was incapable of, but as with ABC’s bionic shows, the CBS series had a cultural impact beyond these considerations of quality, even allowing for the pre-existing comic-book version. The Hulk is a frequent metaphor for rage, and often name-checked in hip-hop. The rapper known for “Get Like Me” (featuring Chris Brown and Yung Joc) goes by David Banner in homage to the TV character. The Hulk also casts his bulging shadow on professional wrestling, artificial soldiers like The Terminator, shape-shifting characters such as Odo (Rene Auberjonois) of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, and the rage virus of 28 Days Later. Star Trek: The Next Generation launched in 1987 with new menace the Ferengi, the name seemingly a twist on “Ferrigno”. The unflappable Barack Obama had us thinking Hulk: Dwayne Johnson played “The Rock-Obama” when he hosted Saturday Night Live in 2009, and sketch series Key & Peele echoed with Obama’s “anger translator”, Luther, who debuted in 2012, and even appeared with President Obama at the 2015 White House Correspondent’s Dinner.

Banner’s curse isn’t that he lost his wife, it’s that he accepted neither that tragedy nor his own fallibility. Still, being cursed wasn’t such a bad thing on Cold War-era TV, nor was poverty (The Waltons, The Rockford Files); paying a debt to society (The Mod Squad, Welcome Back Kotter); fleeing the authorities (Logan’s Run, The A-Team); or some combination thereof (M*A*S*H, Kung Fu). These particular burdens allowed a cyclic story; thus, the viewer could drop in anytime, knowing nothing had changed. Today’s television still likes arrested characters, but we’ve accepted that anti-heroes hold up to repetition better than heroes, even superheroes.