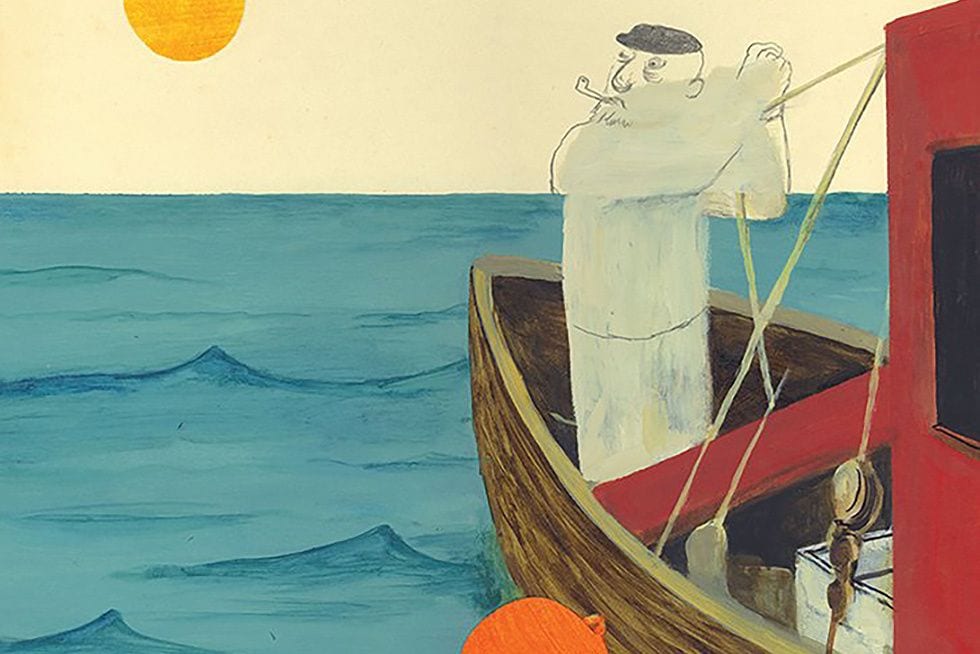

As much as I enjoy US and UK comics, some of the best English-language work is coming from other countries right now. Certainly Drawn & Quarterly and Koyama Press have proven Canada’s oversized presence, and though Fantagraphics is stationed in Seattle (which is sort of Canada?), some of their most exciting releases feature international authors. This month Fantagraphics debuted Danish artist Rikke Villadsen‘s first English-language comic, The Sea.

Though I would be content to read a translation of a work previously published in Denmark, The Sea is significantly more than that. Many comics develop their text and images independently, with artists leaving talk bubbles and caption boxes empty for letterers to fill with mechanical fonts digitally. While this is a reasonable division of production labor — one that also allows for textual revision until pages head for the printer — it can create a visual discord between the pleasant imperfections of hand-drawn artwork and the rigid reproduction of identical letters in identically spaced rows. Too often comics creators ignore the visual fact that words are images too.

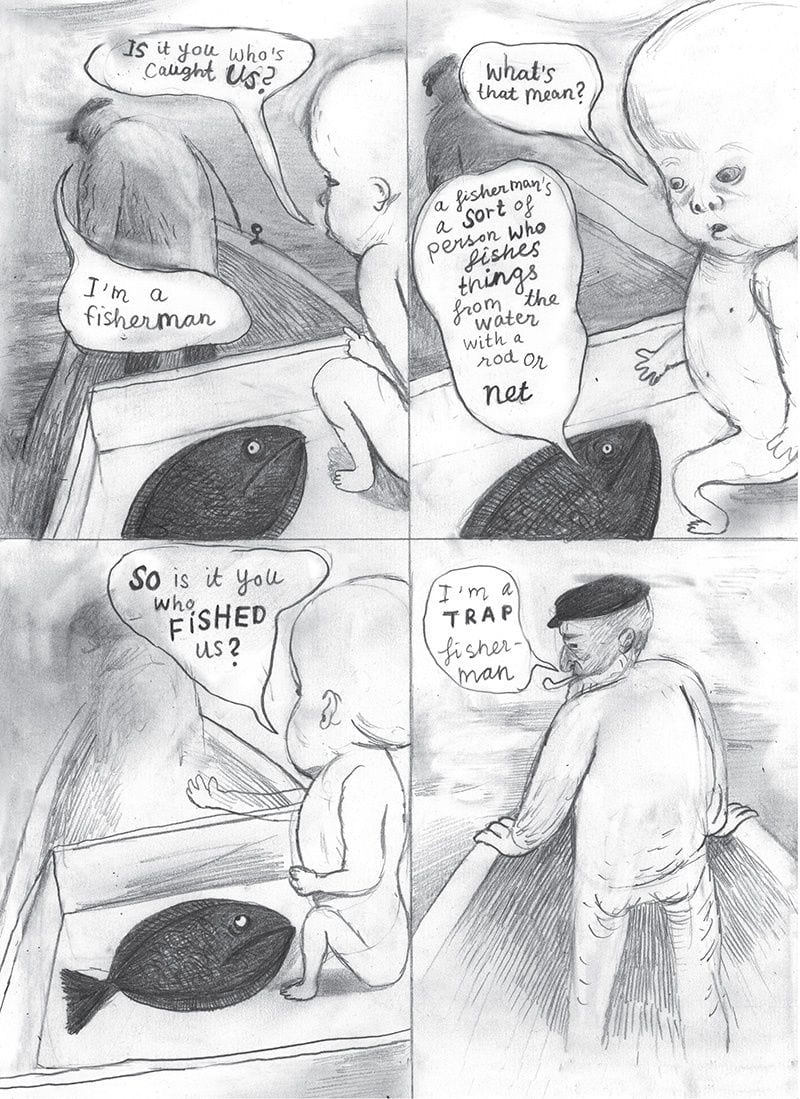

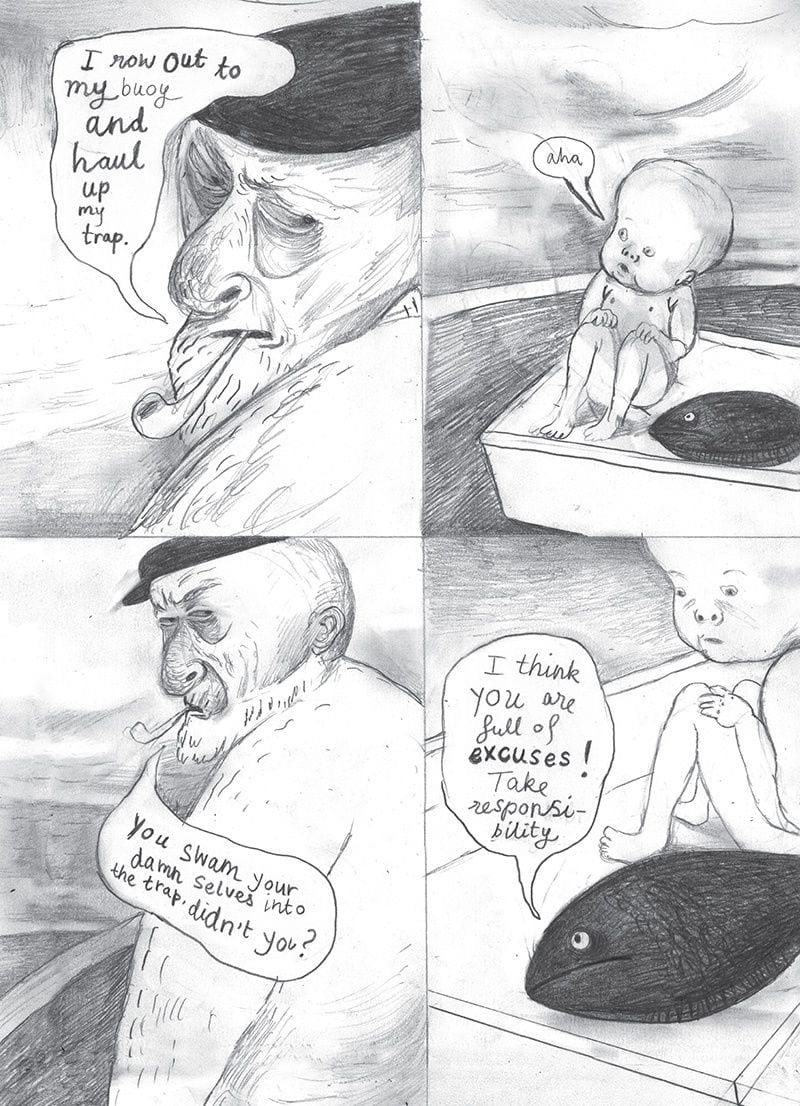

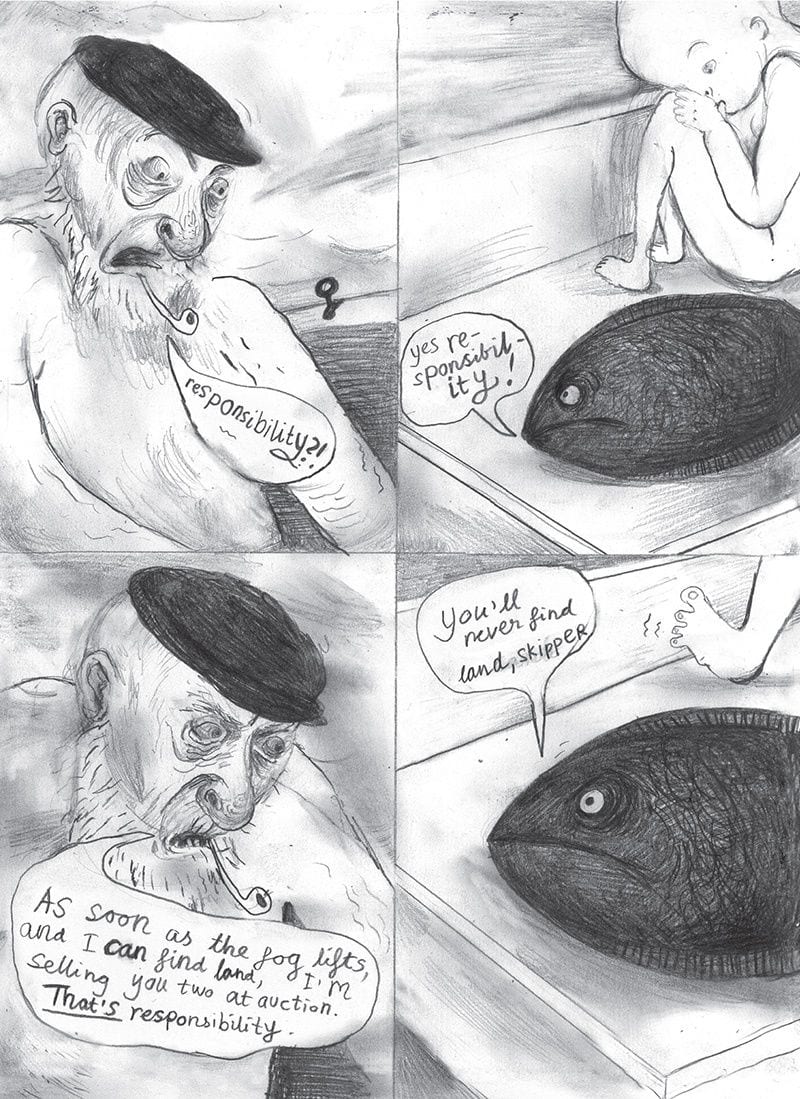

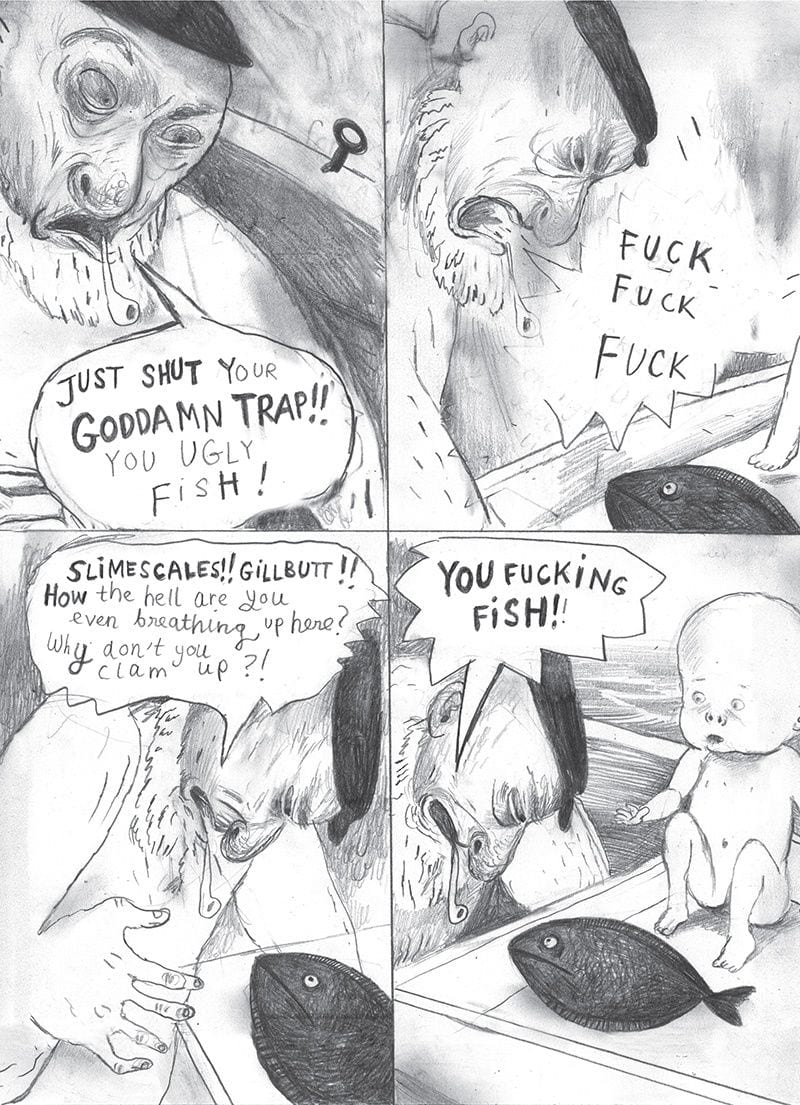

Not Villadsen. All of her words are hand-drawn in an idiosyncratic style, merging script and font and bold flourishes in curving rows that echo the shapes of the talk bubbles that contain them. Translating The Sea into another language would require not simply rewriting text, but redrawing it and so altering all of her original artboards. While a loss for non-English readers, the result is a comic that fully exploits the visual potential of its text. Because Villadsen uses no exterior narration, all of those hand-drawn words also evoke the spoken sound of the characters who voice them, further deepening their visual characterization.

Villadsen’s words, like the rest of the art they appear in, are drawn with pencils. Comics artists typically produce penciled sketches, which they or collaborating artists ink over to create line art that is then colored or printed in black and white. For Villadsen, penciling is not a step in a production process. The penciled pages are her finished product. The Sea consists entirely of pencil marks, from delicate crosshatching to rulered frame lines to the smudged smears presumably produced by Villadsen’s own thumb on the original art.

While colorless comics are common, it’s rare to find the kinds of gray gradations of The Sea—a style ideal for Villadsen’s subject matter, since her main character is lost in the gray waters and gray fog of the North Sea. Though he partially escapes the monotony through what may (or may not?) be surreal fantasies, even the fisherman’s imagination remains caught in the monotone pencils that literary shape him and his world.

The imprisoned effect is heightened by the full-page bleeds and the absence of a formal gutter. Villadsen draws to the page edge (and so necessarily beyond it on her artboards), and rather than framing each panel individually to produce an undrawn negative space between them, her panels share single frame lines. Because the panels are gridded—usually 2×2, with occasional 3×2 and other variants—the combined effects produce a net pattern continuing across pages, as if the story is caught in the same trap that the fisherman pulls from the sea.

Villadsen also draws her main character and his surroundings in a style that at first glance feels cartoonish, because his features are exaggerated and distorted, sometimes as if by the hand of a child, though there’s nothing untrained about Villadsen’s artistic choices. But cartoons are also typically simplified too, with only a minimum number of lines needed to define their most essential shapes. Villadsen instead crosshatches her world with a naturalistic level of detail, producing a visual surrealness that matches her story content when her sailor nets a talking fish and a talking baby.

The graphic novel leaves its watery setting for the first time when the baby begins to recount in image-only narration the circumstances of how he (or she—Villadsen always poses a bare leg in front of its genitals) ended up in the sea. We spend the next 16 pages on the shore where the child’s mother, after scooping up water and boiling it and pouring it back blacker into the sea, removes her Puritan-modest dress and has intercourse with a lighthouse. Villadsen parallels the change in story topic and tone with a striking change in visual style, penciling the mother in naturalistic proportions nothing like the sailor’s distorted features but everything like a pornographic supermodel’s.

If the sane 19-image sequence were drawn by a male artist, I might lose trust in the project overall. But Villadsen knows what she’s doing. Earlier in the novel, the fisherman breaks the page’s fourth wall to address the reader and display his tattoos. They include a sailor meeting a prostitute, four female nudes, a fully-dressed nurse, and a sailor before a tomb marked “In Memory of Mom”. These skin-deep drawings, what that fisherman appropriately calls “painful doodles”, seem to encompass the world of tiny possibilities that he’s able to picture for women. Though the sea is vast, his world, like his imagination, is hopelessly limited, as he sails alone on his small boat through identical gray waves.

It’s no surprise that he refuses to take responsibility for catching the talking fish and baby, instead blaming them for swimming into his net. When they critique his language as insufficiently old-fashioned, he refuses to change, preferring “fuck” to “hornswoggle” or “grumbleguts”. According to his tattoos, he also prefers “fuck” to “True Love”. A tale of his origins follows with his unknown, kelp-smelling father and his shrimp-peeling mother whose breasts creak like tree trunks in a storm.

Though already thoroughly surreal, the story grows even stranger as each building wave threatens to capsize the tiny ship. Ultimately, Villadsen appears to be spinning a circular tale-within-a-tale with no origin or end points and only tragic escapes. What it all means in terms of narrative and the implied gender critique grows as murky as the thumb-smeared fog, but the trip itself is worth the cost of any cruise on Villadsen’s idiosyncratic sea.