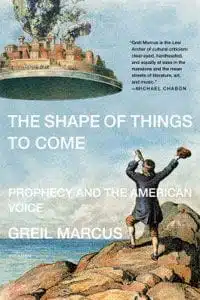

The most fundamental American gesture may be that of defining America as a place that is different from everywhere else. The Puritans were the first to make the gesture, characterizing themselves as God’s chosen people, selected to establish a community that would serve as a model for the rest of the world. Think, for example, of John Winthrop’s 1630 sermon titled “A Modell of Christian Charity.” Greil Marcus does; it is exhibit A in his argument that America, more than any other place, is “made up … It is a construct, an idea.” In his most recent book, The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice, Marcus examines both the nature of this construct and its consequences.

First, though, he establishes the genealogy that underpins his argument. In keeping with his belief that America constitutes a “voice of power and self-righteousness”, he locates this narrative of American exceptionalism in three famous public addresses: Winthrop’s sermon, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s speech during the 1963 March on Washington. All make “certain promises about who [America’s] citizens might be.” The stakes for these particular promises are high — after all, as Marcus notes, “if the country betrayed its promises, it would betray itself.” To define oneself as an exception to the norm, as a shining light upon a hill, is, then, to make a Faustian bargain. Marcus uses the consequences of that bargain, the tension between optimism and despair that it creates, as a lens through which to examine American literature and culture.

He adumbrates this argument in four chapters that resemble conventional cultural criticism about as much as Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of the Star Spangled Banner resembles Pat Smith’s. In readings of work ranging from Philip Roth’s novel I Married A Communist to the oeuvre of the unfairly neglected Cleveland band Pere Ubu, Marcus traces the moral consequences — consequences that are, for him, inseparable from aesthetic ones — of the yawning gap between American promises and American realities. Over and over again, he makes the case that this gap is precisely what gives the films, movies, bands that he discusses their iconic significance, their ability to embody both “the self the country believes it has” and “the self the country suspects it has.”

The ability to hold these ideas in equipoise, to summon the tension between them without resolving it — this seems to have been the touchstone Marcus used when deciding which works to include. He never does articulate his principle of selection, and at times he seems to have abandoned the idea of selection altogether. Example piles upon example, analogy on analogy, with dizzying speed, so that in the course of one chapter, Marcus discusses the TV show 24, John Dos Passos, Philip Roth, his boyhood experience at a statewide civics convention, his students’ response to a class assignment, a Super Bowl commercial featuring a French fry shaped like Abraham Lincoln (in profile, natch), the American installation artist Ann Hamilton, the Firesign Theater, and Sinclair Lewis — along with a few other cultural references too brief to merit mention here. It’s an exhilarating ride — who else could connect so many seemingly disparate things, let alone convincingly? — but, at times, it’s also an exhausting one.

Convinced as I was by Marcus’ readings, I couldn’t help noticing that the primary subjects of all four chapters were works produced by white men: Philip Roth, David Lynch, the actor Bill Pullman (whose face is the focus of Marcus’ second chapter), and David Thomas of Pere Ubu. I hasten to add that Marcus also makes a number of references to the cultural productions of more marginalized groups: he discusses Ishmael Reed, the blues singer Otis Spann, Sleater-Kinney, and the riot grrl band Heavens to Betsy, among others. Marcus is, of course, entitled to create his own definition of the iconic and to populate it accordingly. And, after all, he does select a speech by Martin Luther King, Jr., as one of the focal points of his prologue. Nonetheless, a reader could easily come away with the impression that only the usual suspects are creating works of lasting significance, or at least of enough significance to merit a full chapter’s worth of attention.

Still, Marcus’ book takes up a unique and important task, as discussions of American exceptionalism, and its consequences, have for too long been left solely to academics. We see the consequences of such exceptionalism, taken to a cartoonish and dangerous extreme, in the foreign policy of George W. Bush, yet many Americans, frustrated as they are by the Iraq War, have yet to dismantle the assumptions about American promise and purpose on which it is based. Perhaps this book will help to open a national conversation about those assumptions — or at least encourage other artists and writers to examine them.