As we mark the 20th anniversary of the release of Peter Weir’s social and media satire, The Truman Show, its relevance to America’s media landscape, then and now, seems obvious. The story of a man who discovers his world is an elaborately constructed television show comes across, inevitably, as a prophetic satire of the reality programming that dominated television during its release in 1998.

Looking at this movie today, it’s interesting to consider The Truman Show in light of Hollywood’s unprecedented franchise-based proliferation of sequels, reboots, and remakes, a phenomenon that has been called “peak sequel“. Whereas many sequels feel forced, not least all the Marvel and DC superhero films that dominate the market, it would make sense for a follow-up to The Truman Show to explore what an older Truman has done after he escapes from the artificial world that broadcast his life. This very topic has been the object of impassioned online speculation, with one writer declaring, “I demand there be a sequel.” Nor would the long gap between the original film and now be an obstacle. After all, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Ghostbusters, Independence Day, and even Blade Runner have all seen recent revivals after long periods of cinematic dormancy.

That The Truman Show does not have a sequel, even though it could justify one, holds significance. Looking back on The Truman Show casts fresh light on what’s wrong with peak sequel. In turn, today’s glut of sequels makes it all the more apparent why The Truman Show is so special. It’s not just that film titles ending in numbers are unoriginal, constitute a brazen cash grab, or cheapen the closure of the original film. What The Truman Show highlights uniquely well is how peak sequel robs us of the freedom to interpret movie endings for ourselves and imagine what the characters do next.

Indeed, it’s not hard to imagine several ways a sequel to The Truman Show could go. What if an ambitious young journalist seeks out the reclusive Truman, who has been constantly traveling, trying to outmaneuver paparazzi and evade publicity for the last 20 years? What begins as a quest for a big scoop could turn into a budding friendship. The journalist helps the aging Truman, who has hardened into a disheveled misanthrope, overcome his understandable trust issues and connect with people and places in the real world. More open to the world, now, Truman decides to open a boating tourism service in the Fiji islands, the remote destination he is perennially obsessed with in The Truman Show. (This premise would, like the Blade Runner sequel, also allow there to be a younger main character.)

But maybe it would go another way. What if Truman more quickly embraces his fame in the real world? Maybe he takes a huge book deal and goes on the public speaking circuit. He discovers a way of adapting his playful personality to deliberate performances and public appearances. Meanwhile, the show’s original creator, Christof, has repurposed the expensive, island-sized set into both an actual gated community and a museum of the defunct show, complete with guided tours, house rentals, and of course, gift shops. Christof is unable to make amends with Truman, but Truman eventually reaches an uneasy rapprochement with the actors who pretended to be his loved ones his whole life. Truman eventually finds happiness in a variety of endeavors: he hosts his own travel show where he visits fans of the show around the world; he becomes a UN goodwill ambassador; he sets up a phenomenally successful charitable foundation. And he finally retires to a quiet estate in, yes, Fiji.

Others have mused that Truman might happily travel the world with Sylvia (an extra expelled from the show for trying to disclose its true nature to Truman), he struggles with depression, or even returns in defeat to the show, as Christof predicted Truman would.

These are all juicy brainstorms. But as tempting as these possibilities are, there are far more compelling reasons why such a sequel to The Truman Show would, and should, never happen. Yes, it’s an unwritten rule that artistically ambitious dramas aren’t supposed to have sequels like lighthearted action films. But The Truman Show stands even more pointedly against franchisement because the film is fundamentally about media consumption. Today, any franchise famous enough to be broadly recognizable must continue. The moviemakers have to find a way to keep it going, or else they are leaving money on the table.

Accordingly, The Truman Show would be the ultimate continuously running franchise, since it would theoretically last for an entire human lifespan. We see the show’s viewers wearing hats and buttons that coyly say, “How’s it going to end?” In fact, the franchise would not necessarily end with Truman’s death. It could continue in the life of Truman’s child, and so on and so on, forever. So when Truman triumphantly walks out of a stage door on the edge of his constructed world, he is ending the franchise. He emphatically refuses the obligatory continuation that is so pervasive today, an in-world stand reinforced in our world by the refusal of a sequel.

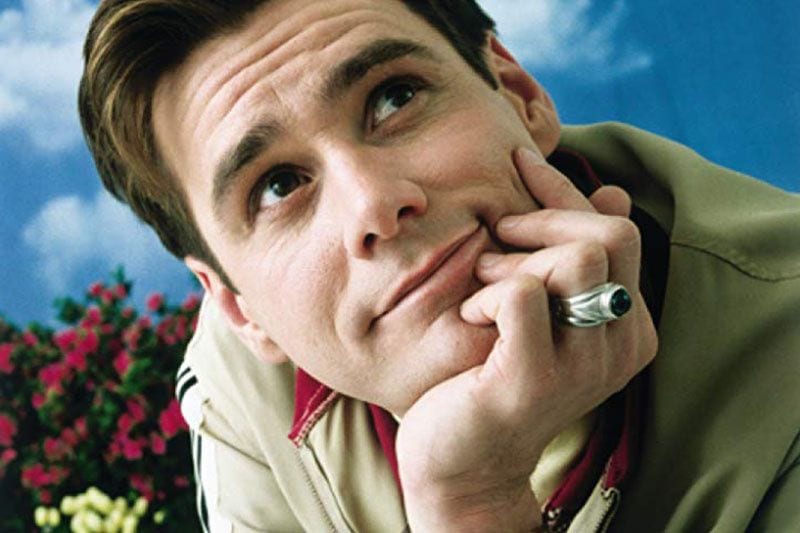

Further, Truman’s sequel-less triumph has a very specific thematic importance. In a recent Vanity Fair feature on the film’s 20th anniversary, star Jim Carrey says: “‘That’s what I see as the ultimate lesson of The Truman Show—when that false life is given up, when what everybody else wants from you and of you is given up, then you walk into the everything. You become the everything. There’s no limitations anymore.'” We should take this idea further by virtue of the film’s reflexive self-awareness, which lends itself to formal parallels between the film’s world and our world. When The Truman Show ends, the lack of a sequel makes the actual viewers participate in the fictional Truman’s liberation. That’s the whole point: we don’t get to watch him anymore. Not having a sequel to The Truman Show is a sign of artistic and moral integrity. By leaving the rest of Truman’s life up to our imagination, Truman is truly free.

The film’s last shot, strangely ironic and poignant at the same time, helps enable such an interpretation. We have just seen Truman’s glorious exit and the ecstatic reactions of viewers around the world who cheer Truman’s heroic victory over the forces that would constrain him. And yet, the last image we see is two security guards lazily watching the static after the transmission stops, and one of them says to the other, “So, you want to see what else is on?” This dismissive reaction satirically undercuts the magnitude of Truman’s triumph. But in another way, it supports it. The guards’ short attention spans suggest that Truman’s viewership will be equally ready to simply move on to the next media spectacle. Truman will drop off the cultural radar, free to pursue his own interests.

Maybe this optimistic take on The Truman Show is naïve. As commentator Emily Chambers has pointed out, Truman would be instantly super-famous and quite unprepared for the real world. Truman would always have cameras following him. The only difference would be that, in the outside world, Truman would know it. So it turns out that the reason a sequel to The Truman Show is so easy to imagine is the same reason that Truman’s post-show life would inevitably continue to deny him the autonomy he seeks. The mundane life Truman had in his show would be impossible. Truman would never really be free to live a normal life away from his unchosen fame.

But phooey on all that. I choose to imagine, against all reason, that by celebrating The Truman Show‘s lack of a sequel, I’m letting the fictional Truman be truly free. By not having a sequel, Truman’s life is forever in a state of potential; he possesses a freedom to live out his own life that he would otherwise not have plausibly had. So against the persuasive notion that Truman would be troubled, unhappy, and stressed, I like to think that instead he’s sitting in a fictional private estate in Fiji somewhere, watching sunsets on the beach with Sylvia. You might imagine something different—that’s the beauty of it.

The Truman Show thus stands as a useful contrast between what the broader phenomenon of sequels imposes on viewers, often against their preferences, and a single narrative of what happens next. It would be nice if today’s filmmakers took inspiration from The Truman Show and took to heart how valuable, how fertile for the public’s imagination, a stand alone film’s existence can be. Just leave it to the audience to enjoy The Truman Show and its noble, quixotic dreams of freedom.