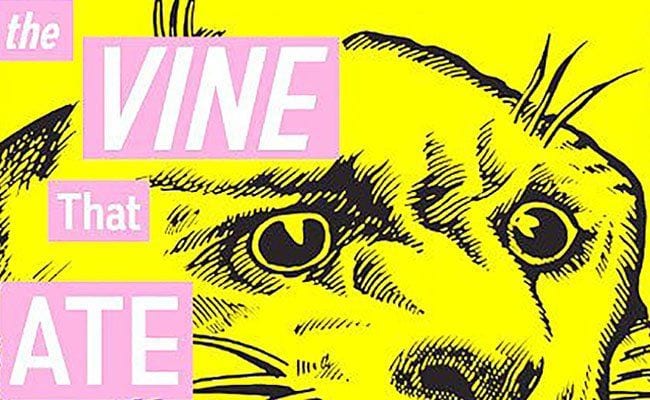

“Best way to plant Kudzu? Hold it out, drop it and run.” It’s probably one of the oldest jokes in the American South. After all, no one who has ever experienced kudzu would even contemplate planting it. It’s also the first line of dialogue in The Vine That Ate the South, a novel by author and musician J.D. Wilkes. Indeed, Kudzu is at the center of this mythic and mysterious tale that opens with our narrator making plans to find an elderly couple who had reportedly been swallowed whole by it.

To say that the narrator is colorful is an understatement. To say he’s a bit of an unreliable narrator is also probably an understatement. He describes his forthcoming journey as his “first and last childhood adventure” — even though he’s in his 30s and tells his readers, “Understand, much of my actual childhood was spent in a state of arrested development inside a fatherless home. I typically stayed out of the sun, alone in the woods or indoors reading books. I loved anything having to do with Greek mythology, philosophy, the classics, or the Bible. Alas, I am now the type of guy who says ‘alas’.”

His search takes him into the most rural parts of Kentucky and is prompted by the most epic of causes: true love. He hopes that his journey will help him win the heart of Delilah Vessels, with whom he lost his virginity and with whom he more recently shared a DQ Blizzard. He’s joined by “expert guide and kindred spirit” Carver Canute. Together they head into a haunted forest in a “forgotten corner” of Western Kentucky.

From here, it becomes the wildest of rides, where concepts like time seem simply to vanish and where we never know what our adventurers will encounter next or when the narrator will choose to flash back and reveal another bit of his past. The narrator’s flashbacks relate primarily to his family. His mother makes regular appearances, but most of the flashbacks focus on the narrator’s father, who dies when the narrator is quite young and whose last words to his son are “SHUT THE FUCK UP AND GET YER ASS TO SLEEP.”

In present day and in the forests of western Kentucky, Carver and the narrator meet a set of equally colorful characters. Some are human but others are not (and some perhaps are halfway in between). There are giants, water serpents, sin eaters, a sad (and abused) buzzard (who perhaps someone ironically ends up being a bit of a hero at the end of the story), and the Bell Witch — a very famous demon from Tennessee. Demons and monsters, our narrator explains, are “as much a part of us as our penchant for fried chicken and turnip greens.”

The idea of what it means to be Southern is as much a part of this book as the search for the couple consumed by kudzu. The American South is a tricky thing. Perhaps more so than any other region of the United States, it’s stereotyped, ignored, branded, rebranded, labeled and ridiculed. In reality, the American South is, as the back of the book states, full of contradictions, and The Vine That Ate the South puts many of those contradictions front and center — through the setting, the various characters and perhaps most clearly through the narrator, who often seems to be a walking contradiction.

With lines like “Trite but true: technology has ostensibly solved most of our problems yet created entirely new ones to take their place” the narrator is, at times, practical and logical. Sometimes — for example, when he comments that everyone knows cicadas hum in the key of C# — he’s hard to take seriously. Other times, he passes by quirky and moves to just downright odd (but strangely enough in a logical sort of way), such as when he hopes that God is “kind of a dumbass. With coke-bottle glasses, mismatched socks, and maybe his fly open. Because how can you stay mad at that?” At other times, he seems almost a throwback to another age with his gentle reader references: “I ask you, gentle reader. No, I beg you! What is it with plastic mannequins and visionaries of the American South?”

Some of the narrator’s contradictions and eccentricities are distinctly Southern, but others are more universal. Toward the end of the novel, he relates with elegant simplicity, “I always thought that growing old and dying was one of the coolest things I’d ever get to do.”

The narrator also voices thoughts on race, family, poverty and obesity. His commentary along with Wilkes’ ability to spin a story and craft language that’s as inventive and clever as the book’s plot combine to create something special that’s a bit of a contradiction itself — a book that feels both classic and new, mythic and modern.