Garbage is a band that could have only come together in the weird, wonderful mad scientist’s laboratory of music that was ’90s alt-rock. An oddly perfect bricolage of goth drama, industrial noise, DIY ProTools bedroom navel-gazing, heartland rock, and grunge angst, the band stormed the music industry in 1994 and the charts in 1995 with a self-titled debut album that ended selling over 2.4 million copies in the United States. This is the Noise that Keeps Me Awake (the title is cribbed from a line from the band’s song “Push It”, the lead single from 1998’s Version 2.0) serves several purposes: a coffee table photo book, a band biography, and a trivia collection for the band, now entering their 23rd year in the business.

The idea that this band would be the subject of such a commemorative volume might have been, at best, laughable in 1994, when big-time producer Butch Vig reconvened with his friend and former bandmate Duke Erickson (they had served time together in the indie band Spooner and the Atlantic Records-signed Fire Town) and former roadie Steve Marker to work on remixes for other artists. As Vig tells it, a remix of House of Pain’s “Shamrocks and Shenanigans (Boom Shalock Lock Boom)” served as the first Garbage demo, with only the original vocals saved from the album version. Soon enough, Shannon O’Shea and her SOS Management Company were daring the trio, who had also provided them remixes for U2, Nine Inch Nails, and Depeche Mode, to make a record. “She kept saying to me, ‘Butch, state a band with Duke and Steve. Take a break from producing other artists. Do it, do it!’” (15) and this led to the early demos that would form the core of the self-titled debut.

The original vision for the band was along the lines of the Golden Palominos, a band with no lead singer but with a rotating cast of guest vocalists. Gavin Rossdale, later the frontman of Bush, was recommended by O’Shea. Ethyl Meatplow’s Carla Bozulich was lined up to audition but backed out to focus on The Geraldine Fibbers.

Fortunately, on 12 September1993, Steve Marker was watching MTV’s 120 Minutes and saw the debut (and only) showing of a video by the Scottish band Angelfish, fronted by Shirley Manson, who had previously played keyboards in the band Goodbye Mr. Mackenzie, but had moved to the lead role in her new band, signed to Radioactive Records. That performance, and her vocals, stuck with Marker and he eventually tracked her down and convinced her to take a train from Edinburgh to London to meet with the band. The meeting wasn’t a smash, and her first audition was something of a bomb, but they kept trying and eventually convinced Manson to come to Madison to record with the group, now signed to A&M Records founders Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss’s new label Almo Sounds, after a furious bidding war.

One of the most interesting aspects of this book is that it veers between straight band biography (written by Jason Cohen) and confessional interview. Immediately after a brief biographical section, the members of the band (and other key associates) discuss the events that have been called up. It’s quite fascinating to hear Manson, the frontperson of the band and the visual centerpiece of the band’s style, discussing her unwillingness to contribute lyrics or ideas in the early days of the band. “I don’t think I was particularly assertive on the first record,” Manson confesses. This wasn’t the only time Manson’s confidence was shaken; as the band’s profile rose, veteran PR man Jim Merlis informed her that, during the first press opportunities, “We’re gonna have to use Butch to sell this record.”

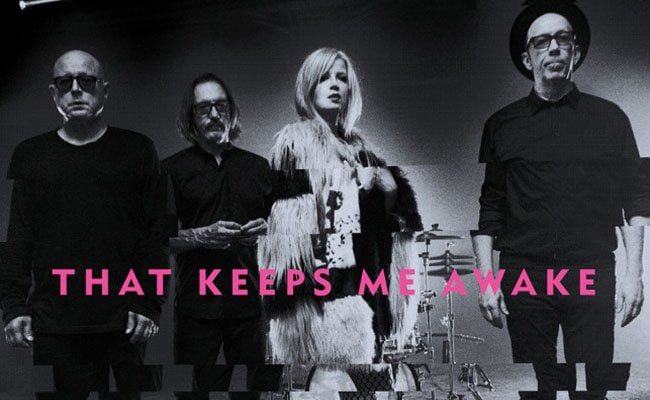

Of course, Merlis was correct, in the sense of the needs of the press: Butch Vig was one of the highest profile producers in the world during this period, having helmed Nirvana’s Nevermind, The Smashing Pumpkins’ Gish, and Sonic Youth’s Dirty over a three year period in the early ’90s. But Merlis, and the band, might have underestimated Manson’s magnetic personality, because she quickly becomes the band’s breakout star and public persona. Her image becomes so central that, by the beginning of the fourth chapter, most of the photos feature Manson in the foreground and her bandmates, often shrouded in blur or soft-focus, find themselves lurking in the background.

Manson’s evolution from uncomfortable frontwoman to fashion icon was rapid. By the time the band began working on the follow-up to the debut, they had been nominated for (and lost) several Grammy awards and performed “Stupid Girl” on the Grammy Awards. Manson wore a Versace dress with sneakers to the Grammys and soon became one of Vogue Magazine’s “Influential Stylemakers of the 90’s”.

The band peaked commercially with Version 2.0, but not for lack of effort on their later albums. As Garbage’s musical family expanded, taking on bass players Daniel Shulman and ex-Jane’s Addiction member Eric Avery, they moved through several management companies. Along the way, they picked up Billy Bush, who moved from the band’s roadie to co-producer and tech guru and, eventually, husband to Shirley Manson. The ubiquitous “label drama” preceded their third record, and Almo Records was liquidated, with Garbage moving to Interscope. While Garbage was a primary focus for Almo Sounds, Interscope was front-loaded with hit making bands at the time.

The third album, 2001’s underrated Beautiful Garbage, also fell victim to terrible timing: the album was released just weeks after 9/11 and the lead single, “Androgyny” failed to get pushed to radio in the wake of the attacks in New York. “Radio banished all sorts of songs, anything weird at all. And this was a song about cross-dressers and transgender people or whatever,” says Erikson, and the album languished. It didn’t help, as Manson recalls, that she was told (well after the fact) that Interscope had to decide whether to “plow their money into Garbage” or to “plow their money into No Doubt”. They chose No Doubt, whose 2001 album Rock Steady sold over three million copies, while Beautiful Garbage topped out at less than a half-million in the United States.

Despite being tour support for U2 on their Elevation Tour, the band struggled. Vig contracted Hepatitis A, most likely from tainted food, while Manson began to suffer from a cyst on her vocal cord. The band limped through interpersonal conflicts and an commercially unsuccessful fourth record, Bleed Like Me, in 2005 before simply going their separate ways for seven years. The band members take great pains, in the interview sections in the book, to note that they did not ‘break up’, but there was little group contact or interaction during those intervening years. The trigger for the reunion was Manson’s performance, at a memorial service for a mutual friend’s child, of David Bowie’s “Life on Mars”. Manson notes that “Butch said ‘You sounded so beautiful. I’ve missed your voice'” and Manson replied “I want to make another record”(154).

The final chapter of the book, and the brief epilogue, deals with the reformation of the group in 2012 for a new record, Not Your Kind of People, on their own label, Stun Volume, which was followed by a triumphant tour for the 20th anniversary of Garbage in 2015 and another new record, Strange Little Birds, in 2016. Heading into their 23rd year, the band has hit some amazing highs: playing a cover of U2’s “Pride (In the Name of Love)” in front of Bill Clinton and Bono in 2003, headlining the opening of the first Scottish Parliament in over 200 years, receiving their own day (Garbage Day, chuckle) in Madison, opening for U2 at Madison Square Garden, headlining the Reading Festival. But the band is still an ongoing concern and the members seem cautiously optimistic that further highlights are still to come.

If this book has a significant weakness, it lies in the brevity of the biographical portions of the text. In slightly less than 200 pages, the band’s whole history is covered, but there are plenty of interesting stories that aren’t explored in detail. For example, the romance (and eventual marriage) of Manson and Bush warrants a few short paragraphs, but little more. The years between Bleed Like Me and the 2012 reunion are mostly covered in a cursory manner. This is most likely a result of the book’s structure: it isn’t a full band biography, as much as it is an art book, and so the limitations can be blamed less on the author and more on the format. Cohen’s biography of the band is crisp and attentive and doesn’t meander, but it does tend to leave the reader wanting more of the juicy details.

The book itself is gorgeous and filled with amazing behind the scenes photos. Some of these photos remind Garbage fans how strange it is to see the usually glowering Manson smiling, including happy shots of the singer with Nick Cave, Kim Gordon, and pro surfer Kelly Slater. Along the way, there are intermittent neon orange pages breaking up the narrative. These orange pages feature trivia, interludes, and other informative tidbits, including the band’s favorite drink recipes like The Champagne Supernova (cognac and champagne), The Black Velvet (U2’s recipe-champagne and Guinness), and the frightening Bufungo Jooce (which requires a bathtub full of ice, fruit, sherbet, and five full bottles of liquor). There’s also a comprehensive discography, a list of the band member’s favorite Garbage songs, and a complete gigography through 2016.

Any fan of the band will enjoy not only the biography, but the aesthetic pleasures of the book’s art and layout. This beautifully designed book is quite the hodgepodge, which seems to be a fitting tribute to a band that also came together in an unusual fashion: a trio of Midwestern studio players, a fish out of water singer from Scotland, and one of the great science experiments of the alt-rock era.