Once upon a time, there was no Internet from which to order music.

There were, instead, small business-card-sized ads poorly photocopied and even more poorly printed in the pages of magazines which were themselves little more than stapled, photocopied zines. These addresses promised free catalogues of music should you write to them (sometimes they requested a dollar for photocopying or postage). And so if you wanted to discover music, you wrote to them: a handwritten letter, politely requesting a copy of their catalogue, sealed with a stamp and deposited in a postal box.

And then if you were lucky, two or three months down the road you might receive a reply. The reply was usually a sheaf of photocopied pages, at best of zine quality, and stuffed into an envelope (sealed with a stamp) and deposited in the mailbox hanging outside of your house or apartment. The photocopied catalogue was usually a chart listing band names, album titles, and prices. The ink was faded and gave out at points, and deciphering the square boxy fonts of a dot-matrix printer was like a form of exciting, musicological excavation. If you were lucky, there might be a single line description of the album. You consumed the listing voraciously, every band name and every album title generating a myriad of fantasies in your head as to what it might sound like. Einstürzende Neubauten? Z’ev? Muslimgauze? Throbbing Gristle? There was, of course, no online music in those days to sample a band or album; not even a Wikipedia to read about them. Music magazines – at least for alternative music – were few and far between, and probably not carried in your town’s bookshops anyway, and so all you had to go by were the names and listings on the page.

You could ascertain certain limited bits of information by studying these listings. A band with several albums to its name was obviously serious about its work; the fact this distributor carried so many of their albums also suggested they were clearly somebodies in the musical scene unfolding before your struggling, pre-teen eyes. Likewise, bands which appeared frequently on compilations: clearly they were sought after by the compilers. And a band that appeared on a compilation, or a split single, next to one of these successful artists, also held some promise.

There were also certain keywords drawn upon by bands in particular sub-genres. The ritual noise artists drew upon arcane magickal terminology. Ambient electronic bands seemed to love astronomical references. French album titles denoted neofolk. Anyone using German in their work must be on to something good.

But just as often, your order from these catalogues was a total stab in the dark; pure guesswork. When the albums arrived, they were more often than not cassettes. Unlike CDs or digital music, both vinyl and cassettes are difficult to speed through; it’s easiest to simply let the entire album play, regardless of whether you like it or not. There is a benefit to this: the listener is forced to develop a sense of the entire album, as an album, without pausing tracks and returning to it, and without skipping ahead if you get bored. You are forced to consume an entire product in a sitting, and this gives you a much broader sense of what it and the artists behind it are about. It’s akin to the quality of a student’s term paper if they actually read through all the books and articles on which they’re drawing as research, as opposed to those who simply skim and search for keywords or look for quotes to pop into their paper to fill in space.

The aesthetic understanding of a listener who listens to entire albums is profoundly deeper and greater than the listener who skips and skims. That is not to say there is no reason to skip and skim – once CDs appeared I became proud of the ability to tell whether I’d like an album, and whether it was original or not, within 10 seconds of listening to it – but that the experience and insight of a listener who takes the time to consume entire albums is different, in a very profound way, from the musical curator who skips and skims.

These were the parameters in which music was consumed in the pre-Internet era of the 1980s and 1990s. Understand, then, the impact of Throbbing Gristle: a band whose legend by then already preceded them. As CUOM Transmissions, the art collective which preceded TG, they were infamous for provocative and daring art actions (including the use of bloody tampons, severed chickens’ heads, and sexual acts on stage), which were broken up by police on at least one occasion. They even faced obscenity charges (for which they were successfully prosecuted, but the jail terms were suspended). They were famously denounced in the British House of Commons as “wreckers of civilization”. Emerging coincident with, and then in the wake of, punk rock they had to be even more daring and provocative than the punks in order to avoid being grouped in with them; a task at which they succeeded ably. They were in a category all of their own. Quite literally: when Throbbing Gristle took to the recording studio their ‘label’, Industrial Records, would give birth to an entire genre of music.

Growing up in North America at the tail-end of Throbbing Gristle’s infamy, the impact of the band was profound. Their daring artistic acts still pushed the boundaries of the taboo in a comparatively puerile and innocent North America, but few people actually knew what to make of them. When your experience of a band like Throbbing Gristle – whose presence is most concentrated on provocative stage performances – is purely aural, one develops a different sense of what the band is about. Remember, again, this is before the era of widespread video recordings and before the existence of an Internet across which to share them. So all you were left with, in the end, was the music. This provoked an interesting conundrum for a band like Throbbing Gristle: they were entirely plausible musically, and even enjoyable for those who could cultivate a taste of the unusual and experimental, yet it was hard to fully understand what they were about without having the background context of their daring performances and art actions. For many of us in North America, we only had the music.

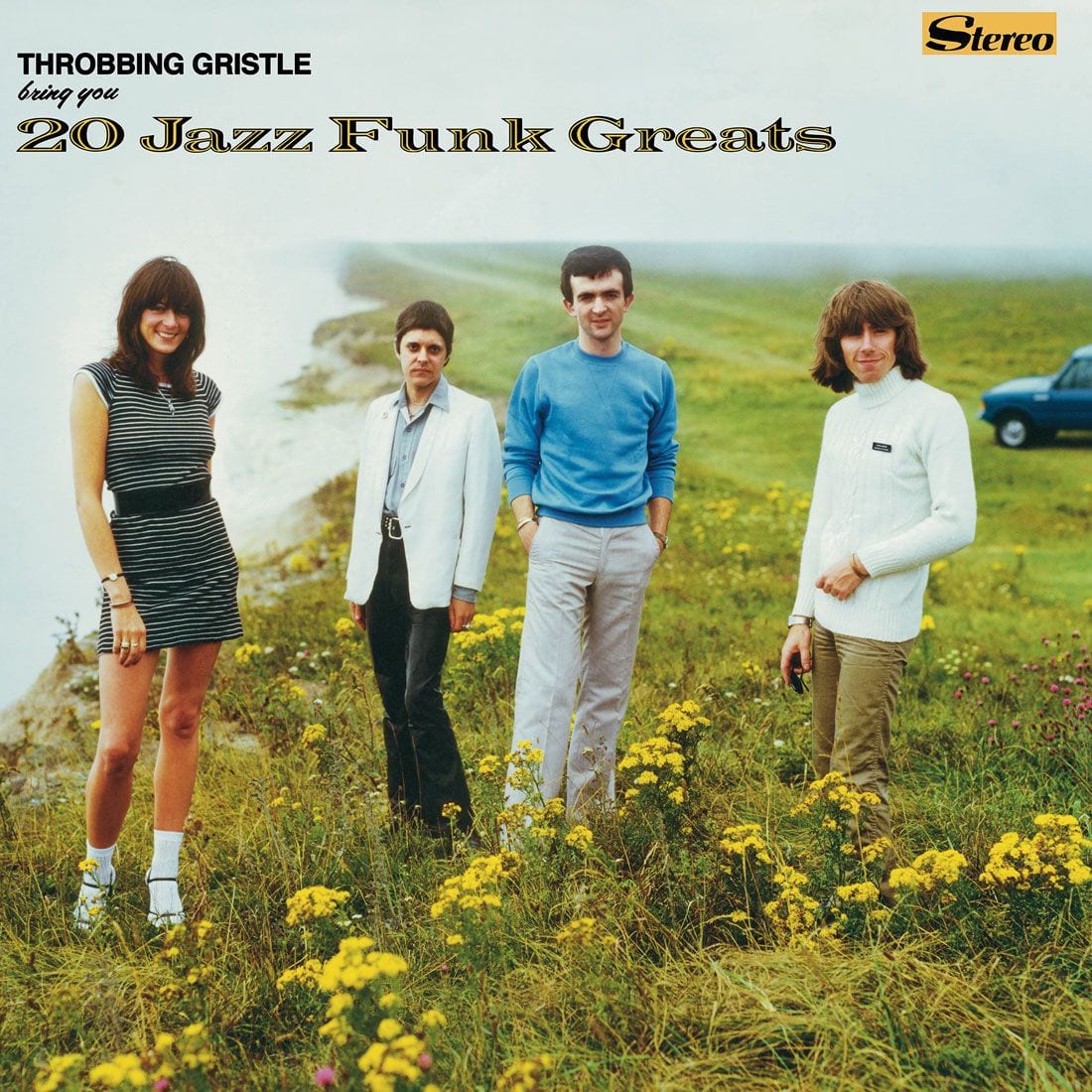

Their album 20 Jazz Funk Greats (1979), for instance, deliberately spoofed the insipid commercial jazz-pop albums of the day, so as to lure in unsuspecting listeners. Some of the tracks on that album resemble danceable techno-pop, further obscuring what the group was all about. And then the material on their ‘Annual Report‘ compilations – available on multi-copied, sketchy cassette format from those ubiquitous mail-order catalogues – were random collections of angry and ugly noise experimentalism; shouts and groans and poorly recorded noise and drony guitars and screams and computerized pulses and tones.

Yet the overall impression of this is what mattered, and it sent a message: anything is possible. You could record pure noise, you could scream and combine simple electronic rhythms and package it in something replicating (yet also vaguely mocking) bland mainstream pop; you could provoke and mail obscene things through the mail and as long as this is all done in the name of art, somebody – even at the receiving end of a mailbox in distant, rural North America – will listen, enthralled, and appreciate what you’ve done. What matters is originality, daring, creativity, inventiveness. To generate controversy is to shatter the complacency of boring suburbia, to offer hope and potential to inner-city urbanites, to shake a threatening fist at the establishment ethics of acquisitive city dwellers.

The potential of Throbbing Gristle, in the pre-Internet era of mail-order catalogues and cassette compilations, was massive. Their legacy, in the post-internet era of identity politics and postmodern ethics, continues to offer a broad landscape of questions, controversies, and potential. For Throbbing Gristle, it means their recordings are more broadly accessible, as is our understanding of the troubling politics and actions which characterized the members’ interactions with each other. The internet and all the information which now resides at our fingertips has vastly increased our knowledge of the artists to whom we listen. We are less reliant on their carefully crafted self-presentation; more skeptical and more informed with what might be called (in hindsight) ‘the facts.’ Does this diminish their potential, or increase it? There are compelling arguments both ways.

What is the meaning of Throbbing Gristle for the present age? What does a repackaged collection of albums, remastered and rereleased, offer the present and how does it affect the legacy many listeners grew up with? Does the value of a remastered collection lie in its ability to provoke, or in its contribution to historical musical appreciation? Does the re-release of remastered recordings still have power and potency as a challenge to the art and music of today, or is it a simple legacy project; a pension project for aging musicians in a world that offers no security to its greatest artists?

Let’s listen to three re-released Throbbing Gristle albums, then.

Mission of Dead Souls: a live performance, recorded in San Francisco in 1981. The final live performance of the group before their (first) breakup. The overarching experience is one of ambient menace. The deep bass throbbing; the disdainful chanting of Genesis P-Orridge, whose voice was seemingly built to pierce through walls of distortion and ambient fuzz, tinged with echo effects which only deepen the ritualistic tone. Instrumentation is used sparingly here: a deep thud echoes and resounds, and the musicians grab it and stretch it out, distort it, kneading and flattening it until that single tone covers the entire track. Electronic chirps and beeps and hums emerge spontaneously from the humming darkness of ambient space. Tones and pulses form the soundtrack for this album, their constant presence a throbbing heartbeat that fades and rises discordantly. Occasionally something resembling beats emerges to accompany P-Orridge’s atonal, ritualistic chanting.

Heathen Earth (1980) is a similar beast (as similar as any of TG’s implicitly unique and one-off performances could be); if anything it is more subtle in effect. It was one of the first Throbbing Gristle albums I ever listened to, and today it packs just as much power as it did then. On the cassette version I had of it, the cover was a dark, ritualistic image that perfectly conveyed the experience of the album. One imagines a vast plain, studded with druidic monoliths, with the dark sky and slit moon glaring overhead. Within the ritual circle is the band; simply you and they, enveloped in the throbbing pulses and noise, losing yourselves in the droning buzz of the cosmic vastness and the warm, seductive chanting of P-Orridge’s voice.

Throbbing Gristle’s performances, like much early ‘industrial’ music, frequently mimic tribal drumming, and often even include traditional instruments such as bone flutes and cornets and other wind and percussive devices. Yet they complement these with harsh, loud electronics – machines that are often used with a blunt simplicity, as though they were not expressions of technological sophistication but harsh weapons turned to ritualistic purpose.

Journey Through a Body (1982) is the most diverse of these three albums. Tracks like “Medicine” are true to the image they denote: a beeping medical tone pervades the track, which otherwise echoes the throbbing, droning pulses of the two live performances. “Catholic Sex” and “Exotic Functions” take a more whimsical instrumental direction, at times merging into the warm beats and vaguely techno-like electronic rhythms that would characterize TG member Peter Christopherson’s later work (along with Jon Balance) as Coil, at other times drawing in a literal zoo of sampled jungle animals. “Violencia” continues the sampling – here with human moans and cries – coupling it with electronic tones, hisses and buzzing, and in the background ever-emergent instruments: a triangle being struck; piano keys being beaten. “Oltre La Morte” turns into a full-fledged piano piece, but the listener’s reaction to it is shaped profoundly by the effect of the previous pieces. What would otherwise be an unremarkable bit of piano muzack is now accompanied by the expectation, and the vague intimation, of a sense of menace; something seems a bit off, troubling and wrong; if only because the normalcy of the track is unlike anything that has preceded it.

Listeners accustomed to the bland sounds of today’s music, who expect structure and familiarity, will be unsettled by these albums, which was doubtless the intention of the artists. But for those who are open to what they have to offer, they provide a warm, enveloping sea of sound and ritualistic tones, a true aural experience that leaves a profound sensory impression. It’s something worth remarking on, that despite the sophisticated and Internet-mediated technologies which have emerged in the decades since these albums were first recorded, they still leave a greater impact than much of the technologically complex music which has succeeded them.

- Throbbing Gristle: The Taste of TG - PopMatters

- Throbbing Gristle

- Throbbing Gristle: The Gristleism - PopMatters

- Interpretations of Genesis: An Interview with Genesis Breyer P ...

- Throbbing Gristle: Part Two: The Endless Not - PopMatters

- After Cease to Exist: The Far-from-Final Report of Throbbing Gristle ...