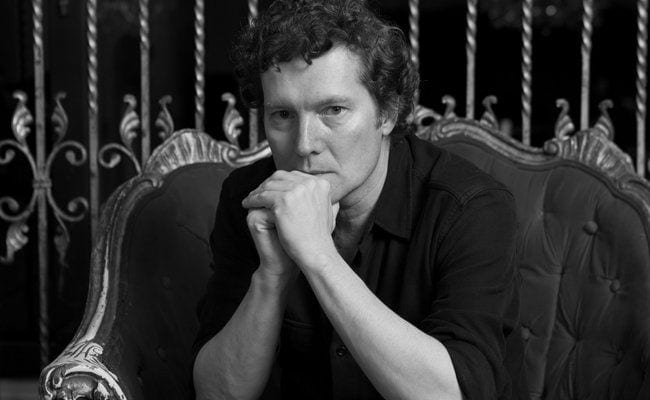

On his most recent solo records, Tim Bowness fixates on things that fade. Abandoned Dancehall Dreams anchored its mini-narratives on the image of a dancehall in a state of disuse. Stupid Things that Mean the World focuses on objects and relationships that, over time, come to look trivial or pointless, even though the underlying significance never fades away. On Lost in the Ghost Light, Bowness takes on a peculiar narrative of an aging musician who, as the title suggests, struggles to capture the thrill of his glory days. As the lyricist and vocalist for No-Man, a duo featuring progressive rock giant Steven Wilson, Bowness has penned some of the most devastating lyrics ever put to album. His mastery of melancholy extends to his solo records, where he weaves sorrow and beauty together with a deft hand.

Despite Bowness’ often moody lyrical meditations, things in his musical career have never been better. Bowness’ online retailer, Burning Shed, remains a hotbed for progressive rock, art rock, and experimental music. He recently finished another album with Peter Chilvers, with who he made the 2002 album California, Norfolk. Then there’s Lost in the Ghost Light, Bowness’ third solo LP in four years, which easily stands out as the strongest of that lot. Unlike the wispy ghost staring blankly into a mirror on the cover of Lost in the Ghost Light, Bowness’ new music is among the most vivacious he’s ever written.

Bowness has always been linked with progressive rock circles, particularly for his involvement in No-Man, but up until Abandoned Dancehall Dreams the style of prog proper was absent in his solo work. Lost in the Ghost Light represents a full embrace of progressive rock’s golden era: the second halves on tracks like “You Wanted to Be Seen” and album highlight “Moonshot Manchild” feature propulsive, climactic build-ups driven by electric organs and serpentine guitar riffs. The spacey atmospherics on the acoustic ballad “Nowhere Good to Go” evoke the chillier sonic landscapes on Pink Floyd‘s mid-’70s records. In fashioning a story about a musician seeking to re-light the fire that burned so brightly in prog’s halcyon days, Bowness re-creates the inimitable sounds of that era while also incorporating them into the style he’s crafted beginning with Abandoned Dancehall Dreams.

Much has happened for Bowness since I last spoke with him for this publication; our conversation runs nearly 45 minutes. Bowness, as velvet-voiced in person as he is on his records, is a loquacious interviewee. Several weeks before the 17 February release of Lost in the Course Light, we discuss what it’s like to be a musician in 2017, looking back on the late ’60s and early ’70s, wondering just how the music world ended up where it did today.

Your decision to write an album about a musician “in the twilight of his career” is interesting, given that you’re in an especially productive part of your career. What inspired this image of a fading musician?

I saw someone in a local supermarket who looked like a kind of classic Mick Fleetwood rocker, but I didn’t recognize him. Given the area that I live in the moment, it’s quite possible that he was in a band like Stackridge or Tractor in 1973. There was such a level of intensity in his stare. I speculated about what band he might have been in, which led to a lot more speculation. That was one of the starting points.

Also, in working with different musicians and Burning Shed, I meet many musicians who’ve been through phases in the industry: people who’ve been committed to a revolutionary time in music to being less so. I’ve always been fascinated as a fan of music how, in Happy Days terminology, you “jump the shark”. I wanted to write about someone who came through a revolutionary era, and I chose the late ’60s and early ’70s because it’s a time period that always interested me, as it was a time where people were making music that they felt could mean something to a lot of people – in addition to making a lot of money and having success. Then I imagined what it might feel like to suddenly become irrelevant, old, and useless with the changes in music technology: physical copies becoming unpaid streams. After all, that’s happened, people in that position start playing to audiences their own age, in so becoming a player on a “golden oldies” circuit.

I was interested both in that journey and why it would happen, as well as its effect on the creativity of that person. What’s the psychological effect of a life like that? Somebody asked me — I’ve become friends with Peter Hammill, who went through that era — whether he was an inspiration, but he’s precisely the opposite. He’s in the five to ten percent of musicians from that period — you could add Peter Gabriel, Robert Fripp, and the dearly departed David Bowie to that group – who managed to ride the changes in the industry.

I have come across people, both fans and musicians, who are locked into one point in history. Of course, it’s also a fear that you yourself can become locked in a particular period or mindset. But there isn’t really any autobiographical element beyond the fact that any musician is frightened of irrelevance or repeating themselves.

Is your local music scene conducive to these aging rocker types?

Where I am now, it probably is. I’m originally from the northwest of England. I was born and brought up in between “the twin towers of evil”: Liverpool and Manchester. I was about 20 minutes from both of them, two bustling, exciting cities. When I started making music in the ’80s, there was still a fantastic local scene in both places. It was great for radio, rehearsal, and releases; it was an exciting place to be brought up in.

At the moment I’m closer to Bath — I’m on the outskirts of Bath — and it’s brilliant in one respect: I’ve never lived in a place where there have been more professional studios. Given the state of professional studios, that’s some achievement. Amongst them is Peter Gabriel‘s Real World studio. Oddly enough, the music scene has lots of people from previous generations, so you have people like Peter Hammill, Peter Gabriel, Rupert Hine, people from the old vanguard of progressive music.

It was then quite cutting-edge in terms of the post-punk scene; bands like the Pop Group got started here. In the ’90s it became big for the trip-hop revolution, with bands like Massive Attack and Portishead being big local groups. In the ’00s, Goldfrapp became a huge local band. Weirdly, throughout the years, the scene here has always been associated with left-field art pop and art rock.

In terms of the newer bands, probably like a lot of places, the scene is producing some relatively interesting bands, but the opportunities – as they are for most up-and-coming artists worldwide – aren’t as great as they would have been 20, 30, or 40 years ago. Since I’ve moved to this part of the area, I’ve met several musicians who live relatively nearby, like Peter Hammill, David Rhodes, and Rupert Hine, but also some newer bands who are interested because of my involvement in Burning Shed. So, interestingly enough – and I don’t know whether it’s entirely typical – but the bands to tend to be on slightly on the left field of contemporary indie. It’s always been a creative hub, but how much of that is new is questionable.

You just evoked the line from your song “The Great Electric Teenage Dream” about how in the present day, music, which was “once a record,” has now become “an unpaid stream.” With your music and your work in Burning Shed, how do you feel about where the industry is headed now?

On one level, it’s in a precarious place, and on another level, there are all sorts of green chutes of optimism – we have a lot of extremes at the moment. Streaming, which doesn’t really allow many musicians to develop a living from making music, is important in that it introduces music to people who otherwise wouldn’t hear it. I’ve always been interested in discovering music; I have my own tastes and prejudices, but I will always listen to what’s out, even if I’m not interested. I kind of work on the basis of “know thine enemy.” [Laughs] Sometimes at the end of the year I’ll listen to “the best albums of the year” that I’ve not bought or heard, to at least come to a conclusion.

Ever since iPod and downloading came in, I adopted them and adapted to them, but I’ve always bought physical products – I don’t know how unusual that is. I use streaming and Spotify sometimes as a buying tool: if I’m investigating a certain band or type of music on Spotify and something really moves me, I’ll buy it. I know that’s something bands live on, and if I can, I’ll buy from the band’s online store because more will go to them. I feel a moral duty with Burning Shed, and what Burning Shed represents, to do that.

I encountered one American artist this way, a band from Colorado called Ian Cooke. He approached [Burning Shed] with very interesting music: a sort of contemporary art rock project with elements of Radiohead and XTC, that sort of spiky art rock/post-punk. He adds a classical minimalist element to that as well. I bought something of theirs from Bandcamp, and now we deal with them.

At the moment, vinyl has also had a massive resurgence – now it’s probably selling ten times more than what it was eight years ago. It’s still a small percentage in the overall industry, but it is significant.

My personal view of this is that whatever happens in any generation, an action breeds a reaction. If you think of the time of punk, for example, when I was around 12, what was interesting — and what a lot of people don’t realize about the history — while there was this sort of street-level return to basics, on another level the stadium bands were selling more than they ever sold. There were extremely bloated concerts like [Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version of] War of the Worlds. Jazz-rock was going through a sort of heyday. If you look through the gig listings of late ’70s Manchester, you’d have the Buzzcocks, but also Brand X — the absolute antithesis.

That’s maybe what’s happening [with vinyl] now that streaming is cheap, free, and extremely convenient. For the casual music fan who maybe ten years ago bought their One Direction single from K-Mart, Spotify is exactly what they need. But the serious music fan, who wants to engage with the tactile nature of product – artwork, sleeve notes, lyrics – they’ve gone more towards vinyl. What we’ve seen in the last ten years is a move to more people streaming, because it’s far more convenient – and I don’t blame them for that – as well as people buying things on the more expensive end of physical releases. We at Burning Shed found that deluxe editions and vinyl are selling better now than they ever have in our 16-year history. That doesn’t negate streams, of course; it’s the case of an action breeding a reaction, the antithesis existing alongside the thesis.

I personally prefer engaging with music in the physical way, even if I’ve heard it twice on Spotify: it’s more personal, intimate, and fulfilling. I remember when I was 11, 12, and 13, when I bought my first albums, that they meant a lot because it was my pocket money. When you’re younger and you spend money, you make a point of really engaging with the music. If you’ve dismissed it once, twice, or three times, it might be the fourth time that you discover the sophistication of the music or lyrics. It makes you work harder. With Spotify, it doesn’t make you work hard: it gives you an impression. You can dismiss that impression quite quickly.

You’ve talked about how your first studio record, My Hotel Year was a “Tim Bowness solo album in name only,” in contrast to the music you’re making now. With Lost in the Ghost Light being your third record in four years, do you have an idea of what makes a “Tim Bowness solo album?”

The reason why I described My Hotel Year in that way is because at the time, I was working on three or four different projects, and not all of them were coming to fruition. I thought, “I know, I’ll combine them.” So it always felt episodic, very bitty to me. What made it coherent was the mixing and selection of songs, but it never felt like an “album statement” to me.

Page Two

With Abandoned Dancehall Dreams — which began as a series of demos with the view for No-Man, as the followup to Schoolyard Ghosts — Steven said he would mix it, but he didn’t have the time to make a No-Man album. I took him up on that and developed the material, and in the end it became my version of a No-Man album. Stupid Things that Mean the World came directly out of that artistic period. Certain albums are a reaction to what’s gone before, whereas others are a continuation. In No-Man terms, Flowermouth is a continuation of the more ambitious elements on Loveblows and Lovecries. Together We’re Stranger is a continuation of the abstract elements on Returning Jesus. But Wild Opera was an absolute turn, a reaction against the beauty of Flowermouth and Flame [Bowness’ 1994 album with Richard Barbieri]; it was a necessary creative step.

With Stupid Things that Mean the World, it came out of what I felt as being very “me” in Abandoned Dancehall Dreams. With the new album, it’s something of a reaction, a departure, in that I was working towards the story of the album. I was also in a sense deliberately setting the music and lyrics in the era of the musician the album’s about. I set myself parameters for the style, sounds, and the story. The interesting thing is that when you’re working within limited parameters, it produces more invention by necessity. The very nature of that discipline gets more out of you.

Pete Townshend and Roger Waters always said that that as they got older, they could only think in more conceptual terms. I understand that. When I go into a project, it always helps if I have an overriding idea, theme, or atmosphere. With Abandoned Dancehall Dreams, it wasn’t a story, but it was a set of stories that came from a single idea of the faded glamour of an abandoned dancehall and all the people who would pass through it. Stupid Things that Mean the World is about obsessions that, from the outside, look totally meaningless, but to the interior monologue of the person it’s vital – whether it’s a childhood obsession with a toy or an older obsession with a faded relationship.

Lost in the Ghost Light is the first time I’m working with a proper narrative. I started off with this idea in 2009; a few of the songs ended up on Abandoned Dancehall Dreams and Stupid Things that Mean the World, like “The Great Electric Teenage Dream”. With the specific story in Lost in the Ghost Light, I went back to the material I’d written for it because I really wanted to complete it. When I did, suddenly – in the spring of last year – I experienced a flood of writing, and I saw how I could finish it without repeating what I’d written previously. There’s one exception, which is “Distant Summers”.

“Songs of Distant Summers” appears on Abandoned Dancehall Dreams. What it represented, I didn’t want to rewrite lyrically, because it said exactly what I wanted it to say. That’s one case where I “recycled material” if you like.

When shaping the narrative of Lost in the Ghost Light, were you drawing at all from any influences in the world of other narrative forms like literature and film?

I think they did overall, but I can’t think of specific writers who would have influenced this. I’ve always been influenced by literature and certainly film; the arts often feed on one another. Sometimes you can, for instance, see a film that moves you emotionally and excites you to write again.

I’ve always been drawn to writers who have said a lot with very little. For that reason, I’m attracted to Harold Pinter and Raymond Carver. They speak to me directly because with almost minimal effort they express maximum emotional intensity.

Philip Larkin is a poet I’ve always liked for a similar reason, although he’s certainly a type of writer than Pinter or Carver. John Betjeman had a similar feel but in a perhaps more antiquated way. They both manage to express quite large historical or personal themes without being pretentious or overstated.

There are still a core set of literary influences that excite me and will be in the background. I’ve continued to discover new writers in addition to those. I like Chuck Palahniuk for his hypnotic intensity. Although he deals with horror themes, there’s something quite literary about his work. I’d say the same about Irvine Welsh; although he’s often seen as a writer who deals with contemporary and shocking themes, in some ways, even though he uses Scottish vernacular, his writing can be quite classical. I’ve always thought of Trainspotting like the classic educational model of the 19th century because it’s a character going through turmoil to eventually come to a satisfying conclusion.

In terms of lyricists, I’m a big fan of Joni Mitchell, the departed Leonard Cohen, Roger Waters, and Pete Townshend. But I don’t think my style is remotely like theirs; I can’t say my style is particularly influenced by theirs.

As with Abandoned Dancehall Dreams, you in your album notes for Lost in the Ghost Light write that you played some of these songs for Steven to see if they could work for a new No-Man album. What’s the relationship between your solo music and No-Man?

When I write, I don’t write with any particular thing in mind. What ends up happening is that you get carried away with a project. With Abandoned Dancehall Dreams, Stupid Things that Mean the World, and Lost in the Ghost Light, I get carried away by the nature of the projects – where the music is going, where the lyrics are going – until it becomes all-encompassing. Once you’re involved in a project, it becomes all you think about.

The album I’ve recently finished with Peter Chilvers is thematically linked, but musically it’s nothing like Lost in the Ghost Light. In some ways, it’s a continuation of California, Norfolk in that it’s intimate singer-songwriter material with contemporary electronica and atmospherics. With our new album, I became preoccupied with the nature of aging people living in cities, and also going back to one’s hometown to right wrongs. One of the songs is about a man lying in bed with his wife, who has Alzheimer’s. Another is about a character going back to see his father, who has a debilitating illness, in a small-town environment. I didn’t intend to write about illnesses or death in the way that I was doing, but that’s what came out. Projects themselves become all encompassing; they draw and drag things out of you that are obviously there.

When I first heard the hard rocking guitars on “Kill the Pain that’s Killing You”, I was reminded of your one-off collaboration with [prog metal supergroup] OSI for its Blood album. The rock and metal edge is something that’s cropped up on your past three records; are you inspired by heavy music?

I’ve got interests in them. With No-Man, if I ever suggested using harder elements Steven would be bored; he didn’t want it because he could do that with Porcupine Tree. That’s perhaps one of the reasons why on the last few No-Man albums, the dynamic range is slightly diminished because Steven saw No-Man as a vehicle for a different kind of expression. For me, I was interested in utilizing those elements; if you listen to the No-Man albums leading up to Wild Opera, there are some pretty extreme dynamic ranges. I’m always drawn to the melancholy, the slow and the miserable, but I’ve also been fascinated by the way dynamics can be used, whether it comes from bands like King Crimson or Tool. I quite like the fact that these bands can go from a whisper to a scream, from a haunting and dark to something apocalyptic. These are things I’ve wanted to explore in my music, and I occasionally do.

What’s the idea behind the phrase that tiles the album’s second track, “Moonshot Manchild?”

“Moonshot” is the name of the band the central character was in. I use it for two reasons: on one level, “moonshot” is the launching of a rocket to a moon, and on another level, it means “big idea”. It’s a metaphor for a person’s big idea; the creation of the internet was “a moonshot”. I’ve heard that Google uses “moonshot” to encourage employees to come up with big ideas. Perhaps the great optimism, innovation, and experimentation in culture in the late ’60s were tied in with man’s quest for the stars. In reaching the moon, we achieved a sense that we could go beyond ourselves. I had wondered if that idea infected the film, music, and literature of the time, which would explain why those arts were so fantastically ambitious. If you think of, say, the late ’70s – and I’m a fan of many punk and post-punk bands, so this isn’t a criticism – you could argue that by that time, everything was grounded and rooted. This was not something “looking to the stars”, something with a Stanley Kubrick 2001: A Space Odyssey vision. “Moonshot” is meant to represent the unique creative vision of the late ’60s/early ’70s.

“Manchild” has to do with the main character, who is in his late ’60s. He’s still singing the songs of his youth to an aging audience. I remember when I first got into music in my early teens, and I’d talk to people in their early 20s who would say things like, [gruff voice] “Oh yeah, I remember the ’60s.” It was like they were veterans of the first World War – it was crazy. They were married in their mid-20s with kids, and their lives creatively were for all intents and purposes over. Since that time, you now find people in their 50s, 60s, or 70s who are as passionate about graphic novels, music, television, and cinema as they ever were. I’m not sure if that’s producing another generation of “man-children”; that’s another debate. The “manchild” on my album is someone who achieved his one moment of transcendence in the late ’60s and early ’70s, and now has fallen into a repetitive lifestyle in a golden oldies circuit.

With your career in music now spanning several decades, do you feel that pursuing music has become more of a “moonshot”, perhaps for the reasons you articulated earlier? Do you feel you’ve reached the moon?

I think I’ve been exceptionally lucky, as an accident of birth to be quite honest. When I was growing up, local radio in major cities was open to playing music from up-and-coming artists. We only had four radio channels, and yet those four channels would dedicate their 8 PM – 2 AM slots to exciting new music. It’s inconceivable now, but I would get my demo tapes played by DJs in the mid-to-late ’80s alongside the brand new Cure or Kate Bush single. That was lucky.

It was also lucky that Steven and I got record deals [for No-Man] in the early ’90s, which is one of the last times you could get proper deals. It’s equally lucky that we were allowed to develop an audience in one of the last times when there was an enormous appetite for physical product. That probably died in the early ’00s, although there is a degree of resurgence with vinyl and other forms.

One of the other inspirations for Lost in the Ghost Light is a great Brian Eno quote. He felt that professional musicians are like blacksmiths, a symbol of a fading time. While writing the album, I wondered if it was like a wildlife documentary about an endangered species. Steven and I are perhaps some of the youngest examples of people who have been able to follow our dreams in music.There are, of course, younger people in a similar position like Radiohead and Elbow. But now a lot of artists making experimental and left-field rock or pop music, if they aren’t involved in a highly commercialized scene, are starting off in their mid-30s at the earliest if they’re making a career. If I were 17 or 18 right now and I were starting off in music, I know what I’d do creatively, but I don’t know what I would do to get people to listen to my music. If you think of Bandcamp and Spotify, you are just a tiny dot amongst millions of tiny dots.

I’m not sure how you make yourself visible these days. Local gigging circuits are virtually nonexistent. The aforementioned area in northwest England, which once had four radio stations, now probably has about 60 stations. Those stations, which are largely digital, are either playing golden oldies, chart hits, or talk radio. The opportunity for forward-thinking creative music to have exposure on a larger scale is certainly lesser.

When I think of British media, even a liberal outlet like the Guardian has extraordinarily mainstream music coverage. When you look at someone like Steven, who is selling records and getting in the charts, he’s still apparently not worthy of the place that will be given to Kanye West or Beyoncé. It’s utterly bizarre that now to get exposure, even in left-field music magazines, you’ve got to be very big. Of course, there’s been a reaction to that: the success of genre magazines like Prog in Britain have proven that music that isn’t in the mainstream can have its own cult magazine that gets put out in shops. But that’s quite rare.