Where is the seat of love? Is it in your lover’s face? Is it in the angle of her nose, in the little crooked corner of her mouth when she smiles, in the way her eyes reflect back at you when you’re looking at her? And is her face your center of gravity? Her eyes the portal to her soul? Is this what fills your vision when you think of love? Is this identity, is this recognition? Does nothing else — the way your hands fit perfectly, the way your bodies mesh, the way your thoughts converge — does none of this matter, in the end?

And so what if one day, after a spat, after your lover — a bit crazed by jealousy — complained of you “growing tired of the same boring face”, and she simply vanished, no note, no explanation? And what if one day, months later, after weeks of pining, you met someone new, who might remind you a bit of your lost lover — something in the way she touches you, or a certain look, even her similar name? What if you started to fall in love? What if you were moving on, finally, after so much loneliness and longing?

But what if, unbeknownst to you, you were actually falling in love, again, with the same woman? What if she had, hope against hope, returned to you, finally — only you didn’t know it, not yet? What if, driven a bit mad by jealousy, and despair, she went under the knife, had her face permanently and unrecognizably transformed into a new version of her old self? Or is it a completely new self? Who is she now? Is she your old lover returned, or a new lover supplanting your memories of the old?

And then what if she decided to test your fidelity, the depths of your love? What if she then set you up to think that your old lover had been returned? What if her new altered self then flipped out in a jealous rage when you decided to spurn her for her old self? What is this? Is this love, is this insanity? Where does the one end and the other begin? And then when you figure it all out finally, when recognition begins to set in, when you realize the monstrosity of what she’s done — what do you do then?

This preposterous scenario forms the eye of the storm in South Korean director Kim Ki-Duk’s Time, a film which at first glace seems to be a dark brooding Hitchcockian love story. Unless, that is, it’s really a philosophical meditation on identity and oblivion. Or unless it’s really just a screed against South Korea’s epidemic rise of cosmetic surgery. Or maybe it’s all three, or none of the above and I’m missing something even more profound.

It’s hard to tell with Kim, one of the most enthralling, infuriating and enigmatic director’s to come out of South Korea — or anywhere, really — during the last ten years. An obsessive’s obsessive, his films all tend to be monomaniacal in focus, ruminating on grand spiritual/ philosophical concerns which remain forever hopelessly opaque, even after repeated viewings. He may be a genius, he may be a charlatan, but there’s no denying that when he’s on his game, his best films achieve that rare feat of making the mysterious and inchoate universal longings visually manifest on the screen.

Kim’s films make sense on a primal level, as well as a spiritual one, bridging the disconnect between body and soul. They defy explanation and criticism, seem to speak in a forgotten, non-aural, language. Indeed, most of his recent films, starting with 2000’s brilliant Isle, have been nearly silent, with totally mute protagonists at their center.

Which is why Time, a confused scattershot film, unsure of just what it wants to be and do, is such a welcome relief and entirely apropos given the confusion lying at the film’s center. A holiday from both the oppressive hermeticism of his prior output, and his often overwrought obsessiveness (odd, since on its surface, Time is pretty much about obsession, and nothing else), Kim’s messy thriller/ love story/ tragedy is the first film I’ve watched of his where he seems to loosen up, to actually enjoy himself.

Overrun by divergent ideas that are seemingly at war with one another, pulled in several different genre directions at once by Kim, full of uncharacteristically frank dialogue that for once complements and deepens the action on the screen, Time appears to be a turning point for Kim, who seems to want to descend from the rarified airs he usually travels in, but is unsure of how best to go about it. I like how Time‘s own hesitation and uncertainty of its identity as a film reinforces and complements the identity crisis of the protagonists. Does it matter if this formal complementarity is deliberate or not?

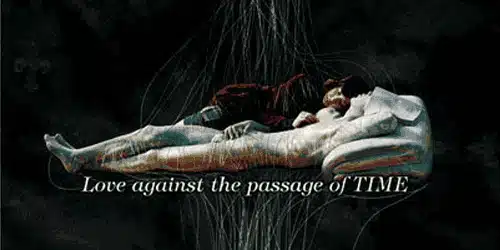

And does it matter if, in the end, none of the above questions are answered? Can they be answered? Can they even be asked? Is the asking of the questions admission of defeat, before we even begin? Where does the “I” reside? And when does it vanish? What is left when it disappears, and what takes its place? And is love possible, if we can’t even know this? With time on one side, and oblivion on the other, trying to pull us apart, or crush us, how can we hope to survive? What are we trying to keep intact? Are our only options either giving in to the relentlessness of aging, or giving in to the obliteration of our self through some inhuman transformation? Time‘s final shot, looping back around to its opening scene in a Mobius Strip, is irresolute, a concession to incoherence of identity and love, a confession of defeat in the face of the relentless march of time.

Aside from a two-minute trailer which basically gives away the whole movie, Time’s only extra is a 40-minute long, behind the scenes featurette, which is quite literally nothing more than exactly that. No interviews, no illuminating comments from cast or director, just setting up shots, positioning actors, and wrangling with cameras. I guess this isn’t necessarily a bad thing – Kim’s films would lose much of their mystique with any sort of explicit explanation. But then, why even tack on anything at all? Sometimes the film itself really is enough to justify the DVD.