For more than three decades before his passing in 2016, New York Times photographer Bill Cunningham — dressed in his trademark french blue sanitation workers’ jacket — would ride around on an old, cheap beater bike in New York City snapping photos of fashion on the streets. Cunningham not only believed “the streets reflect what is going on in the political world”, but that people’s clothes from all walks of life capture “beauty”. A modestly self-described “fashion documentarian”, whose work remains a cornerstone of the fashion and street photography, Cunningham is the primary subject of first time feature director Mark Bozek’s affectionately drawn The Times of Bill Cunningham, screened at the New York Film Festival 2018.

The film, briskly paced at 74-minutes to capture Cunningham’s own peripatetic energy, is a blend of archival footage from Manhattan’s fashion scene between the early ’60s to mid-’90s, and an on-screen fireside chat between Cunningham and Bozek, who remains behind the camera. While this structure indicates a formulaic biopic, Cunningham insists that as a fashion and street photographer, he is “not the story”. Bozek honors Cunningham’s vision, emphasizing instead the times Cunningham lived in and his artistic processes to capture fashion (for a more probing take on Cunningham’s personal life, see Richard Press’s 2011 documentary Bill Cunningham: New York).

In this regard, Bozek juxtaposes photos from Cunningham’s conservative Irish-Catholic upbringing in Boston — his plainly dressed parents and rows of colonial homes — with those of a dapper young Cunningham happily working part-time gigs in chic fashion shops to learn how to be a milliner. In another lovely chronicle, Cunningham happily recounts the termination of his halfhearted advertising job at the luxurious Bonwit Teller Department store on 57th Avenue in Manhattan: the then early 20s fashion maverick was fired when the store learned that his own hats took attention from the store’s line.

Stories about quietly cultivating his craft during leave while enlisted in Paris, France for military service during the Korean War, and later scraping together “nickels and dimes” from several part-time jobs to buy supplies at the New York City garment district, paint a story of a man who continued to create in all circumstances. Here, Bozek’s selection of footage skillfully suggests that while “the times” during which Cunningham existed were challenging, there was also an edifying human connection in the artistic community that allowed iconoclasts to achieve.

An array of photos capturing Manhattan’s ’60s milieu, including those from the Carnegie Studio apartments in which Cunningham resided with the likes of Marlon Brando, Norman Mailer, and Isadora Duncan, convey a communal commitment to rich, diverse artistic expression. Here, there is less emphasis on a rigid categorization of artistic mediums, or on today’s staggeringly isolating wealth gaps between “A-List” celebrities and “starving artists”.

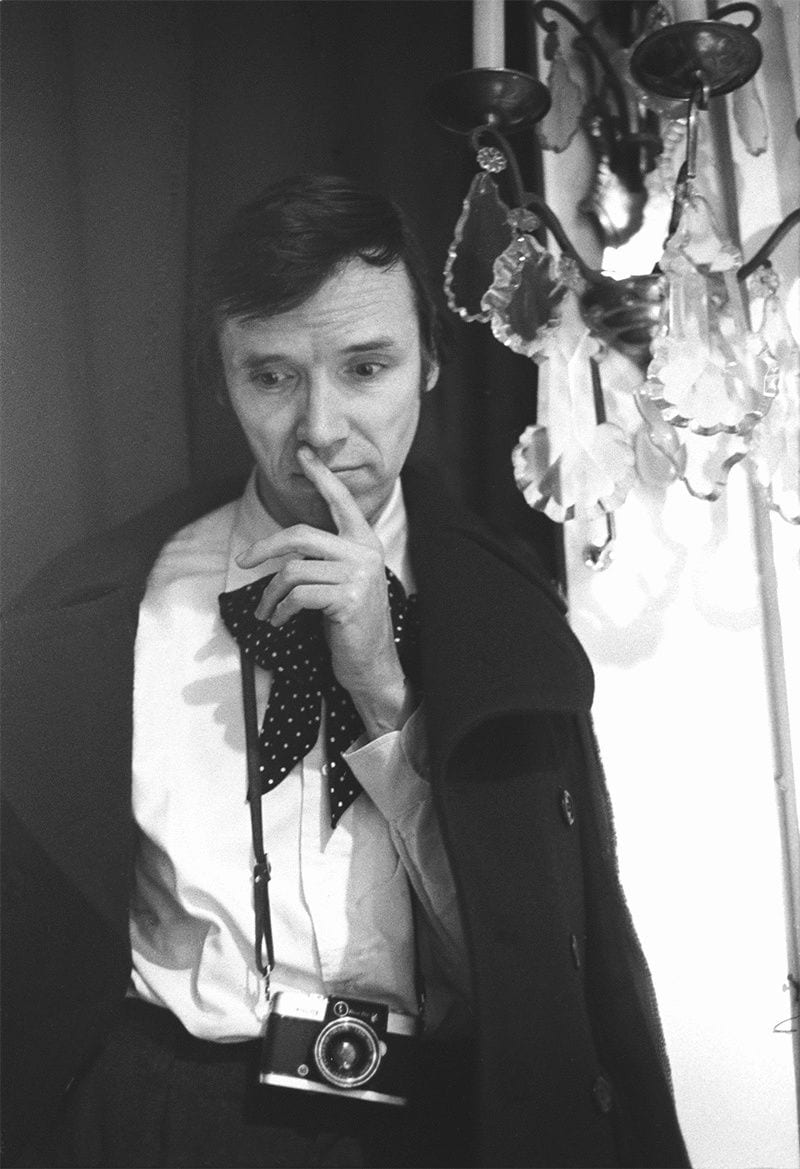

After a mid-’60s stint in fashion journalism at Women’s Wear Daily, where Cunningham realized his surrounding colleagues were “real newspeople” and he was decidedly not, Cunningham made an ultimate career change into photography when a friend loaned him an Olympus half-frame camera, known as an “idiot box”. The crisp, organic street photos from Cunningham’s “idiot box” subversively questions whether digital smartphone cams, with their emphasis on digital filters and computer editing, are improvements in photography. Likewise, Cunningham’s lively account of the 1973 Versailles Fashion Show, where fashion and counter-cultural revolution synergized to “press on the raw nerve of the time”, is not only a wistful homage, but a critical inquiry as to whether modern fashion has since reached this cultural apex.

The film is loaded with photos and accounts of stylish celebrities, socialites, and fashion icons; a sampling of whom includes future first lady Jacqueline Bouvier in the early ’60s, Greta Garbo (a fortuitous photo of whom propelled Cunningham’s star in the late ’70s), and Vogue’s former editor-and-chief, Diana Vreeland.

But even when Bozek and Cunningham enter this rarefied terrain, Cunningham refreshingly brings the discussion back to artistic critique. He decries living luxuriously, instead opting to live modestly in a studio among his photos, and to fly coach to fashion shows; as Cunningham argues, he does this to remain as an appropriately detached documentarian of the fashion world. Indeed, Cunningham’s style has quite a bit of merit. In what initially appears like a bit of knavishness, Cunningham notes that movie stars of the ’50s like Ginger Rodgers and Elizabeth Taylor did not have “style”. But later clips of a vast spectrum of people walking on the streets, from Upper East Side socialites to low income city residents, capture the sincerity of Cunningham’s point: he trained his eye to strictly to see fashion’s contours, which is not to be confused for celebrity mystique.

The Times of Bill Cunningham occasionally hits saccharine notes, particularly when Sarah Jessica Parker‘s linking voice-over unnecessarily lionizes Cunningham as a premiere Manhattan artist. Moreover, there’s little time to soak in any single Cunningham photo, as his collection is presented in a whir — to be sure a deliberate move to capture Cunningham’s prolific work, but still, an imperfect decision given the film’s emphasis on Cunningham’s eye for craft and detail.

Yet these are minor criticisms, given the film’s remarkable breadth for such a compact screen time. In addition to his insights on fashion, Cunningham conveys a generous vulnerability when discussing the seemingly paradoxical intersection between his shyness and his monastic routine of hitting the streets to take photos. Indeed, there’s a messy range of emotions in the arts, and Cunningham shows remarkable empathy toward artistic struggle by speaking so openly about his own limitations.

Notably, The Times of Bill Cunningham was recorded in 1994, and as a happy accident. Bozek, who at the time was a fashion reporter looking to do a ten-minute interview, wound up having a conversation with Cunningham which lasted for hours. This story is a subtle statement about an era before speedy reportage and narcissistic instant gratification in photography metastasized into the arts, thereby restricting the more leisurely and thorough playfulness necessary for robust, lasting artistic discovery.

But of course, an era isn’t entirely responsible for cultivating new, enriching forms of art. As The Times of Bill Cunningham captures, such definition also takes a person who fervently sticks to an artistic vision and a sense of oneself, either along with the times, or in spite of them.