little blue robot by vinsky2002 (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

It is no longer surprising to suggest that that there exists a buried pessimism underwriting Pixar’s hugely popular Toy Story franchise. Known for its family-friendly charm and its sophisticated embrace of computer animation technology, many have also pointed out that Sheriff Woody’s melancholy story of attachment and the eventual, inevitable, abandonment awaiting all toys encroaches on some rather bleak territory. In a positive review of Toy Story 3 (2010) for The Guardian, Peter Bradshaw, nonetheless, writes that ‘nothing deserves its U certificate less than this brutally adult movie with brutally adult themes: the origin of evil in childhood pain, the death of childhood and, well, just death.’ (“Toy Story 3”, 15 Jul 2010)

In many ways, the release of

Toy Story 4 (2019), almost a decade after the previous instalment in the Toy Story ‘trilogy’, marks a satisfying postscript to the series’ long-standing preoccupations with mortality and morbidity. Allaying early fears of a cynical ‘cash-grab’ (as Richard Seymour reminds us, there has always existed a profound economic imperative at the core of Toy Story, with its quasi-spiritual connection between young consumers and their possessions), the film picks up from the emotional conclusion of Toy Story 3, in which a collegiate Andy (John Morris) donates his toys to four-year-old Bonnie (Madeleine McGraw). Once more, we find Woody struggling to accept his diminished lot in the toy hierarchy: no longer a favoured toy but a fungible object, left to collect dust in the cupboard.

And yet, under a certain light,

Toy Story 4 also appears to be the most plainly optimistic of the, now, ‘tetralogy’. Directed by Josh Cooley (his feature debut, following prior credits as a writer on 2015’s Inside Out and storyboard artist for popular titles such as The Incredibles (2004), Ratatouille (2007) and Up (2009), the film surpasses its predecessors as a work of supreme visual splendour: rendering the minutiae of a rainstorm, or (in a slightly more foreboding manner) the membranous layers of dust in an antique store with hyperreal precision. On top of this, Toy Story 4 takes us far beyond the enclosure of Andy’s room, in favour of the glittering lights of the fairground—with its atmosphere of festivity and self-sustaining loop of endless playtime. In brief, Cooley’s addition to the Toy Story universe is injected with something altogether more cosmic in scope.

At the heart of the matter is a buoyant discussion around the possibility of value in apparently worthless matter. In this regard, it will be suggested that

Toy Story 4 stands alone as the first film to partially unseat the ‘brutally adult themes’ referenced above. Chief among these is the unshackled horror of de-animation itself. Where Toy Story 3 is almost crushingly beset by the entropic murk of the junkyard (the film’s climactic moments find the gang drawn, inexorably it seems, into the hellfire of an incinerator) Toy Story 4 stages, both aesthetically and practically, an untimely return to presence—a riposte, of sorts, to the series’ leitmotif that toys are ‘all just trash, waiting to be thrown away.’

Instead, it is precisely the moribund and explicit uselessness of rubbish, represented by the new addition of Forky (Tony Hale), that is imbued with its own grotesque and vaudevillian agency. Constructed by Bonnie in a moment of anxiety and worry, the motley assemblage of spork and toy short-circuits the system of value (previously bound by nostalgia [Woody] and novelty [Buzz]), asserted in the Toy Story movies up to this point. The result, as the following argument will endeavour to prove, is a comedic reverie of all things disintegratory.

Before we begin, it should be clarified that such a breeziness of temperament is by no means totally irreconcilable with the more gloomy philosophical conundra that have always nourished the Toy Story films. From the 1995 debut, and audiences’ introduction to six-year-old Andy’s familiar roster of toys—including plastic T-Rex and Mr Potato Head—comfortable narrative arks and steadfast emotional hooks have been reliably paired with a remarkably unsentimental approach to the imminent destruction of our heroes. A highly abbreviated account finds Woody and the gang variously battered, dismembered, torn, reprogrammed, mauled by animals, crushed under heel, and (in the case of Toy Story 1), gruesomely modified in cruel acts of Boschian horror. Such, we learn, is ‘playtime’: for children who appear to the viewer as increasingly erratic demi-gods, swinging blindly between acts of love and chilly indifference.

But there are also those other moments: ones that elicit an unshakable existential chill. These moments—uneasy combinations of sunshine and dread—stick with you long after the jubilant highs and maudlin lows have worn off.

The beginning credits to Toy Story 1 offer a prime example. We open in media res, finding Andy (Morris) playing with his toys. Acting out a scattershot narrative, somewhere between all-American western and bank-heist caper, his toys are introduced through their imaginary character doubles (One-Eyed Bart, the Dog with a Built-In Force Field). It is typically innocent fare until something rather odd begins to happen. The camera follows Sheriff Woody (Tom Hanks), our protagonist, galloping, in ersatz motion, against a chintzy reproduction of the American desert. Every now and again there is a close-up, resting uncomfortably on the toy’s cold, expressionless face.

With childish excitement, Andy launches Woody into the air; the toy falls to the ground, limp, its lifeless body drooping over in a contorted pile. All the while, the exaggerated bonhomie of Randy Newman’s ‘You’ve Got a Friend….’ plays, mockingly, in the background like some Ionesco-infused farce.

The problem that is neatly illustrated in the opening is thus: much as we grow to care for Woody and Buzz Lightyear (Tim Allen), and their earnest desire to ‘be there’ for Andy, the films appear set on reminding us of the characters’ uncomfortable materiality. They were never alive; or, rather, they were never entirely dead—existing in a kind of ill-defined half-life. It is perhaps no mistake that the Pixar formula—’what if X had feelings?’—is predicated on the irreconcilable paradox of finding sentience where none should exist…

In the late Mark Fisher’s lively review of Thomas Ligotti’s 2010 work of amateur philosophy, The Conspiracy Against the Human Race (reissued in 2018), Fisher locates some unsettling parallels between the toy’s precarious existence and Ligotti’s supremely pessimistic world view. Inspired by the dour thinking of Arthur Schopenhauer, as well as the Norwegian anti-natalist Peter Wessel Zapffe, Ligotti’s terrifying philosophy (a horror writer by trade) invokes the cold, inhuman underbelly lurking beneath the so-called human universe. Furthermore, as Fisher reminds us, Ligotti’s vision of humanity is one engaged in a dark pantomime, a sleight-of-hand away from the more alarming sense that ‘things, including human things, are not dependably what they seem.’

In particular, Fisher points to Ligotti’s concept of the ‘human puppet’ as a potentially instructive category in the, otherwise, rather loose ontological argument staged throughout the Toy Story movies. For Ligotti, there exists a close proximity between the horrifying and the paradoxical: singling out the uncanny horror of the living-dead. Above all, the motif of the sentient puppet, having become ‘self-mobilised’, serves as a chilling reminder of our own uncomfortable relation to the inhuman.

(IMDB)

As Ligotti states, there is little of enduring substance to the human character: merely ‘a thing of parts brought together as a simulacrum of real presence’—’a biological paradox’, he concurs, ‘that cannot live with its consciousness and cannot live without it…’ Pitifully, we play out our lives, in Ligotti’s terms, as string-less puppets, ‘forced […] into the paradoxical position of striving to be-unselfconscious of what we are—hunks of spoiling flesh on disintegrating bones.’

Before one dismisses the connection between the fiercely nihilistic Ligotti and the supremely profitable Pixar franchise, one might do well to remember the word ‘toys’ close etymological link to notions of meaninglessness. Derived from the middle Dutch tuig (‘stuff’ or ‘trash’), ‘toy’ also conceals the more sinister warning of the middle English term for a malignant trick. In this spirit—and in spite of increasing budgets and ever advancing computer graphics—we are drawn back to the uncanny illusion of human presence, by which the viewer is invited to find something human in the dumb materiality of toys.

This is reinforced, as Fisher reminds us, by the toy’s unsettling compulsion to appear limp and lifeless in the presence of humans. During these moments, the unquenchable desire to be useful to children curiously overlaps with the toy’s spooky urge to self-extinguish. Aping Ligotti’s deep ontological pessimism, Fisher writes of the series’ underlying sense that ‘consciousness is not a blessing bestowed on us by a kindly toymaker […] but a loathsome curse.’

And so, play-time continues, stifling the crushing realisation (according to Ligotti’s capitalised mantra) of a life that is ‘MALIGNANTLY USELESS’. This human drive towards unindividuated oblivion is prefaced in Freud’s 1920 essay, “Beyond the Pleasure Principle“. Marking an important turn in Freud’s psychoanalytic philosophy, it is argued that the organic processes that sustain life also exist in close association with the primal call back to ‘the peace of the inorganic world.’

(IMDB)

In thrall to their miniaturised death-drives, the toys in Toy Story habitually find the brute non-being of their material selves to be a greater assertion of their reality than their absurd, ‘paradoxical’ condition as all-too-human puppets. Wistfully recalling the experience of being played with by her previous owner, cowgirl Jessie (Joan Cusack) opines in Toy Story 2, that ‘even though you’re not moving it’s like you’re alive…’

And yet, in the topsy-turvy universe of the Toy Story films it is safe to say that there are few constants—least of all the so-called ‘peace’ of the inorganic world. Nowhere is this clearer than in Toy Story 4, in which a strangely Ligotti-esque vision of a life that should not be elicits some of the more perverse belly laughs of the film. As such, the melancholy themes of obsolescence, uselessness and human puppet-ification are rendered immediate and with a kind of warped levity: as if reflected in the exaggerated surface of a funhouse mirror.

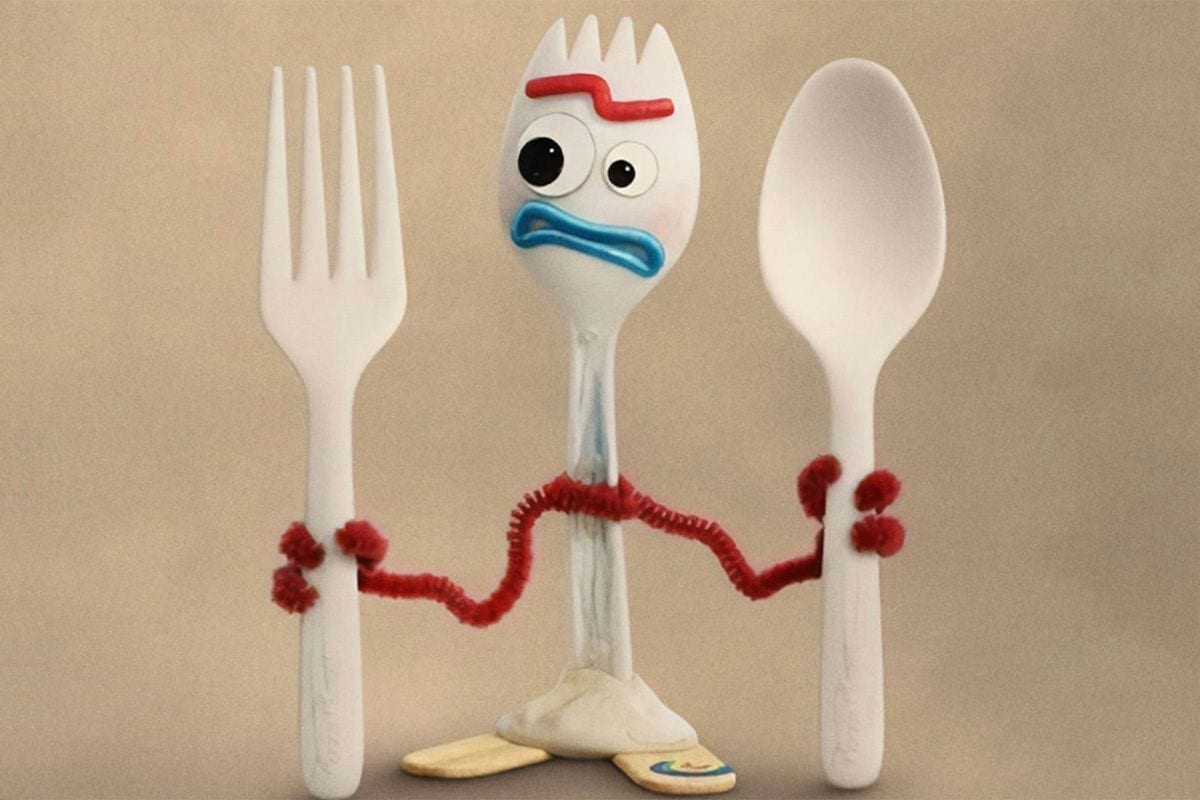

The most concentrated example of this tonal shift can be found through the introduction of Forky. A composite plaything constructed from bits of pipe-cleaner, chewing gum, broken lolly sticks—affixed to the makeshift trunk of a plastic spork—Forky serves as both catalyst and comic relief for much of Toy Story 4‘s narrative. Constructed by Bonnie during her first day of pre-school, Forky is a marvellously throwaway character (quite literally), nonetheless raised to the status of a favourite toy.

On the one hand, the character indulges the franchises’ predilection for absurd comedy; on the other, Forky spectacularly reveals the gleefully arbitrary laws of toydom. Forky has neither the glossy commercial allure of a Buzz Lightyear, nor the old-time value of Woody (revealed in Toy Story 2 to be a highly valuable collector’s item). And while this hasn’t stopped Disney from trying to cash in on Forky as a toy like any other, the character lays bare the vacuum at the heart of Toy Story’s framework of valuation—predicated on little more than a child’s whim.

On top of this, (and with Ligotti’s pessimism in mind), Forky foregrounds the unlikely creation of a kind of inorganic horror, deep within the pit of the Toy Story world. For so much time, Woody and the gang have worried about being reduced to the status of junk; perhaps it would have been better to consider (an arguably more grotesque scenario) the likelihood of rubbish being raised to the level of a toy? It is on this subject that Toy Story 4 lands a number of its most twisted gags.

Bemoaning his enforced consciousness as a toy, Forky complains that ‘I am not a toy. I am a spork. I was made for soup, salad…maybe chilli. And then the trash.’ And while the series can certainly lay claim to their fair share of monsters (Mr Tortilla-head comes to mind here), Forky is notable as the first to have been sired by another toy. Woody’s quickfire act of compassion—if not explicitly constructing, then at least providing the raw materials for Bonnie’s new toy—takes us to the unhappy core of his unresolved attachment to Andy and his own precarious sense of value.

Much like Frankenstein’s monster, Forky betrays more about the constitution of his creator than his own largely unexplained, unbidden, existence. Throughout the film, Woody goes out of his way to preserve Forky as Bonnie’s new favourite toy—this, in spite of the latter’s compulsion to, once again, become ‘trash’. (‘It’s warm, safe, like someone whispering in your ear “everything’s going to be ok.”‘) And yet, despite Woody’s best efforts to remain useful to Bonnie, it is clear that Forky articulates an uncomfortable truth about Woody’s formerly coveted status as a valued possession.

Forky’s prominence belies the toy’s series long phobia of their own brute materiality—exemplified by the tearing of Woody’s arm in Toy Story 2. Cast one’s mind back to the ensuing ‘nightmare sequence‘ (Woody falling through a vast darkness into a dustbin), and one might read Forky as a benign reinvention of the ominous assemblage of rubbish and remaindered toy-parts that end up pulling Woody deeper and inexorably into oblivion.

(© 2019 Disney/Pixar. All Rights Reserved. IMDB)

Still, the film rarely allows itself to become sombre. During a memorable slapstick turn, we watch Forky’s many thwarted attempts to return to the ‘peace’ of the dustbin, all playing to the jovial soundtrack of Randy Newman’s ‘I Won’t Let You Throw Yourself Away’. Unlike its predecessors—littered (often literally) with reminders of the toy’s looming obsolescence—Toy Story 4 comes closer to offering a full-throated affirmation of cosmic uselessness. For this reason, the film partially rebukes Ligotti’s malignant philosophy, steering closer to the somewhat more effervescent nihilism of Romanian essayist Emil Cioran.

Upheld in Conspiracy as a ‘maestro of pessimism’, Ligotti ventriloquises Cioran’s 1964 study, The Fall into Time, in which all sentient life may be considered ‘”an uprising within the inorganic, a tragic leap out of the inert.”‘ At once senseless and untimely, Forky’s predicament—shanghaied, as it were, into consciousness—is baked into Cioran’s bleakly hilarious (and hilariously bleak) world view. In the 1934 volume, On the Heights of Despair, written when the author was 23 years old and in between bouts of insomnia, Cioran asserts his position regarding the essentially lousy condition of all things existing:

“…the passion for the absurd is the only thing that can still throw a demonic light on chaos. When all the current reasons […] no longer guide one’s life, how can one sustain life without succumbing to nothingness? Only by a connection with the absurd, by love of absolute uselessness, loving something which does not have substance but which simulates an illusion of life.” (my italicisation)

When all certainties have fallen away, Cioran argues, it remains for us to hold tight to a ‘love of absolute uselessness’; one must find the gumption, and humour, to stand face-to-face with the human-puppet, having torn loose from its strings, and feel oneself wholly evacuated by the utter senselessness of it all. In Toy Story 4, this sentiment is writ-large during a brief moment of respite, from the otherwise frenetic pace of Cooley’s direction.

In this moving little set piece, we find Woody and Forky following the family’s campervan, by foot, down a dark, empty road. With time to kill, Woody reminds Forky of his value as Bonnie’s treasured toy. However, the longer they talk, the more Woody proceeds to divulge his own backstory, about Andy, and his own feelings of abandonment. In spite of everything, ‘you find yourself after all those years sitting in a closet…”—Forky interrupts, ‘feeling useless?’ This is punctuated with the latter’s light-hearted—albeit loaded—remark that ‘you’re just like me…trash.’ For Forky, everything acquires meaning through its relation to ‘trash’ (‘I’m Bonnie’s trash!?‘), deliberately eliding the firm opposition between the valuable and valueless. In this way, the wretchedness of rubbish is revivified with a modicum of what Cioran would describe as the ‘poisoning sweetness of the absurd.’

Similarly, the disorderly world of Toy Story 4 is presented as one of a unifying, shared absurdity. Following a family road-trip (a treat after Bonnie’s first day at pre-school), the viewer is plunged into the zany world of the funfair: a perfect synecdoche for all things ludic, fragmentary and un-systematic. Along the way we meet some rather loosely characterised new toys: Duck and Bunny (voiced by comedy duo Key and Peele), at times feeling airlifted-in from another movie, nonetheless inject Toy Story 4 with a kinetic slapstick appeal.

Elsewhere, Canadian stuntman Duke Caboom, hilariously falls short of the stunts promised in his advertising campaign—capable of little more than crashing. Elsewhere, we are encounter Gabby Gabby (Christina Hendricks), the matriarch of Second Chance Antiques. Introduced with an ominous Kubrick-ean flourish, Gabby Gabby is a vintage toy (like Woody) tormented by the withheld promise of a child’s love. Due to a manufacturing defect, she has been left with a broken voice box, leaving her unable to achieve the affection of Harmony (ahem) (voiced by Lila Sage Bromley), the grand-daughter of the antique store owner.

However—unlike the previous movies—there are no clear villains in Toy Story 4. There are only toys, variously haunted by the ghosts of children past. Even Gabby Gabby—whose request for Woody’s voice box (pointing to his heart) elicits a brief existential shiver—is revealed to be another broken toy, desperately trying to make herself useful.

Easily the most memorable of these new appearances is the reintroduction of Bo Peep (Annie Potts). Flimsily characterised in Toy Story 1 and Toy Story 2, the post-feminist reinvention of Bo in Toy Story 4 offers a stark counterpoint to Woody’s urgent attempts to reclaim his former status as a valued toy. Where Woody initially recoils from the prospect of living as a ‘lost toy’, Bo’s more peripatetic and improvisatory outlook (since her departure from the group, prefaced in the opening to the film) provides a straightforwardly affirmative view of a life without owners, and without concrete attachments.

Like Forky, the porcelain Bo is literally a body in pieces; in a throwaway scene, Woody accidentally pulls off Bo’s arm, to Woody’s horror and Bo’s amusement. Navigating the chaotic swirl of the funfair, Bo serves to open Woody’s eyes to existence beyond Andy (a manic pixie dream toy?). Gesturing to the limitless expanse of the funfair, Bo announces: ‘who needs a kid’s room when you can have all of this?’

By the end of the film, it is clear that to recover from the loss of Andy, Woody must become, if not like Forky, then a step closer to trash. The surgical removal of his voice box, performed by Gabby Gabby’s gaggle of ventriloquist dummies (was there ever a better metaphor for what Derrida famously described as ‘the metaphysics of presence’?), serves to strip Woody of one of his most characteristically anthropoid qualities. After all, as Buzz’s mechanical ‘inner voice’ indicates in one of Toy Story 4’s recurring gags, the desire for internal harmony can sometimes conversely reveal the naked artificiality of being, peeled back before an overwhelming and blind materiality.

Furthermore, with Woody’s final decision to separate from the gang and join Bo as a fellow ‘lost toy’, it as if the affirmative injunction (common to many Pixar properties) to be-your-best-self, suddenly overlaps with a parallel drive towards becoming the least of yourself. In this way, Woody’s journey, out of the trash and into the cosmic bedlam of the funfair (to infinity and beyond?) marks a surprisingly uplifting advance in the Toy Story series: foregrounding both the unreliability of value and the ultimate consolation of a collective and ineluctable uselessness.

- Part 5: Toy Story 2 to Titus (November - December 1999) - PopMatters

- Toy Story: 10th Anniversary Edition (1995) - PopMatters

- Toy Story (1995) / Toy Story 2 (1999): Blu-ray - PopMatters

- Part 5: Toy Story 2 to Titus (November - December 1999) - PopMatters

- 'Toy Story of Terror!' Delivers on Halloween and the Toy Story Name ...

- 'Toy Story 3' and the Best Scene of the Summer - PopMatters