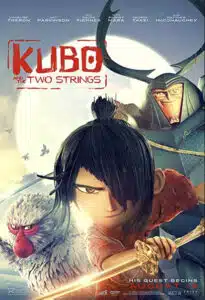

Laika, the independent, Oregon-based studio that brought us stop-motion charmers Coraline, ParaNorman and The Boxtrolls, takes us to a mystical new world in Kubo and the Two Strings, a sprawling Japanese odyssey that follows a young hero as he quests to reconnect with his family. Taking inspiration from Akira Kurosawa, Ray Harryhausen, George Méliès and more, the film is a poetic ode to the power of storytelling as a way of keeping the ones we’ve lost close.

Game of Thrones’ Art Parkinson voices Kubo, a gifted boy who can bring inanimate objects to life with music. When tragedy strikes his family and dark spirits are released into the world, he quests after three pieces of mystical armor his father, the great warrior Hanzo, used to slay the evil Moon King. With companions Beetle (Matthew McConaughey) and Monkey (Charlize Theron), Kubo has the adventure of a lifetime, slaying giant monsters, learning to hone his powers, and discovering the bitter truth behind his family’s murky lineage.

PopMatters caught up with Travis Knight, Laika president, CEO, and director of Kubo and the Two Strings, and producer Arianne Sutner during their recent visit to San Francisco. They discuss Laika’s commitment to reinvention, trusting their audience to receive challenging themes, the passion required to be a stop-motion animator, and more.

* * *

When I watch Laika’s films, I’m sort of in awe. I can imagine the work directors, editors, costume designers and actors do, but the stop-motion stuff . . . that I don’t understand. I can’t imagine the work that goes into it.

Travis: Very few people do, and very few people are drawn to this particular lifestyle. I think it takes a certain kind of person. So many of the artists that work at the studio have stories similar to mine. They were drawn to this field because they had an incredible love and passion for it. There was something they saw at some moment in their lives that just fired off something in their brain that got them excited about this field and this way of making film. Our whole shop is filled with people who are incredible craftspeople.

Some of them weren’t necessarily stop-motion artists. There’s a seamstress, someone who makes ceramics, someone who makes watches. People who are crafty and have an eye for detail–if you can kind of tweak their perspective a few degrees in a certain direction, they can become extraordinary stop-motion artists. We have a whole shop of people from all over the world. One of the things I love about our studio is that it’s a global community. People come from everywhere. I think that diversity of culture helps make our films what they are. They’re really unlike anything else, and I think a part of that is because our studio is unlike anywhere else in the world.

Arianne: They’re great problem-solvers, too. You can work in the costume department, but it’s really about solving little problems every day. We have engineers and scientists and tinkerers, and problems come up every hour, in every department. I think that’s what they enjoy doing, figuring out how to solve problems to make your viewing experience really fantastic.

Travis: We combine history and tradition with disruptive thinking and cutting-edge technology. I think, any time you have these unusual groups of people working together, it creates fertile ground for innovation. We have people who are inventing technologies. Big, throbbing brains like you’d find at NASA. And we have people making films the way George Méliès made them a hundred years ago, with their hands. You have astronauts and cavemen, luddites and futurists, working side by side. It creates a rich environment of innovation.

I think what’s extraordinary about all of your films is that they each have a completely different visual vocabulary. A lot of animation studios’ work has an underlying, base-level style that you can see in each film, but all of your films look unique.

Travis: We absolutely do not want a house style. There is this inherent creative restlessness in the studio. We always want to tell new stories. We always want to challenge ourselves and jump into new genres and new aspects of what it is to be human. Because we’re telling original stories, it doesn’t make any sense that this story, which is completely different and takes place in a completely different part of the world, looks exactly like this other story. Hopefully, the look of the film arises naturally out of the narrative.

Because of what this movie was, the look for this movie was completely different than, say, The Boxtrolls. This movie was heavily influenced by ukiyo-e and origami and Noh theater and late Edo-period doll making. There’s such a rich cultural tradition that you typically don’t see on the big screen. When I went to Japan for the first time when I was eight years old and I was exposed to this incredible art and culture, it was something that stayed with me for my entire life. It’s some something I wanted to see represented on the screen accurately.

It’s a period fantasy. This version of Japan never really existed, in the same way that Miyazaki’s version of Europe never existed. It’s an impressionist painting. We apply that same prism, but we root it in a real place. We do our research and we understand what was happening in these different periods, and it becomes an assemblage of these things, combined with our own imaginations.

Arianne: Something we were talking about recently was building a library, which we have done, but really organizing it so that you see the visual aesthetic and vocabulary for each movie. The hope is that a character from ParaNorman would look wildly out of place in Kubo’s world. In and of itself, the world is perfect. An errant line that is not in the Kubo style will jar the audience. Each movie works for itself.

Travis: To celebrate our tenth anniversary, we took a photograph. We got most of the key characters from all four films that we’ve done and put them together. It was so weird to see them all together! To see them all together . . . they would not live in the same universe. They’re so totally different from each other. We’re always trying to do something new.

One of the things that sets Kubo apart from other family-friendly movies is that it doesn’t pull punches when dealing with challenging ideas like the permanence of death. Grief isn’t a pretty thing, and you don’t depict it as such.

Travis: I do think that part of our approach is that we’re trying to tell stories that have meaning and resonance. We’re not looking to make cotton-coated confections; we’re looking to make films that have something to say. They’re keenly felt, thought-provoking. We really do respect the intelligence of the audience. We don’t speak down to our audience, which I think is, unfortunately, a rarity in so much stuff that’s geared toward families. When I was a kid, it wasn’t like that. There were so many great movies I saw and became such a part of my life. Some of the most meaningful experiences were when I’d go with my parents to the movie theater and go to these new worlds and experience these new stories that resonated with me. Movies have the power to reach us, and I think they still do. That’s what we’re trying to do as filmmakers: tell stories that have meaning.

Kubo is a maturation metaphor about a boy who crosses the Rubicon from childhood to adulthood. It’s about the things we gain and the things we leave behind along the way. There is a cost to growing up. One of the things that you have to learn is how to deal with loss, how to reconcile the unfairness of the universe. People can be snatched away from us through a random act of casual violence, without there being a heroic speech. It’s a film about loss and healing, about how loving someone or something exposes us and makes us vulnerable. At the same time, love also gives us strength. It heals us and gives our lives meaning. There’s something that’s kind of bitter about that polarity, how those conflicting sides of the same emotion make us vulnerable and strong. This film hopefully tackles that in a sensitive and poetic way.

Arianne: Travis’ commitment to not pulling punches is also physical. When the mom hits her head at the beginning of the movie, he consistently committed himself to the sound effects so that you can feel their pain. They hurt. They die.

Travis: Look… it’s not a Wile E. Coyote universe. If a character smashes into a wall, they don’t get turned into a pancake and fly back up again. In our world, people get hurt. Dead is dead. You want to have audiences understand that there are real stakes here, even though it’s a metaphor. Even though it’s a stylized version of real life, it’s still connected to real life.

A lot is made of your film’s stunning imagery. I saw it in 3-D, and it was spectacular. But I think the thing that really makes the movie feel three-dimensional is the sound design. Talk about your approach to both the score and the sound effects.

Travis: It started with the music. Kubo is like an Orpheus figure. He’s gifted with divine magic, divine music. Like Orpheus, he can coax the rocks and the trees to dance. When I thought of a composer who could do that, I thought of Dario Marianelli, who we worked with on The Boxtrolls. He’s such a brilliant musician and artist. Talking him through the big ideas in this movie, he knew it was going to be a challenge. But he was game for it. The great thing about Dario is that he was in sync with me from the beginning. He knew the story and the emotions we were trying to evoke in the music, where we could weave the themes together and make the audience feel what the character is feeling, through music.

We also had this extraordinary sound designer, Tim Chau. The sound is so good. We started talking about the movie with him and, again, he completely locked in with us from the start. We’re creating a world from scratch. We’re not capturing source audio; it all has to be created. From really complex stuff like a raging sea or these mythological monsters to something as simple as when Monkey slams the shell of Beetle’s back shut after he crashes to the ground. Tim is so clever; for that sound, he used the sound of a Volkswagen Beetle’s door slamming shut. So many details. The combination of the sound design and music really lifts the film to what it needs to be. I think these guys did a great job.

What is Kubo’s greatest fear?

Travis: Kubo is effectively an open wound. He’s a kid who’s gone through a horrible experience. And yet, he has a beautiful outlook on life. What he wants above all is to feel the love of his family, to connect with his mother and the memory of his father and really feel what it’s like to be enveloped in a family’s love. Like any kid, he fears that being taken away from him. Any parent fears that being taken away from them. I think we look at that from both perspectives in this movie. We were kids who went through this experience, and now we’re parents with kids of our own. We are the continuation of our parents’ stories, and our kids are the continuation of ours. What we desperately want is to hold onto that beautiful family for as long as we can, and that’s something that Kubo wants. I’m sure his greatest fear is losing that.

Arianne: I think, in the beginning, he wants to not lose [their] tenuous connection as she goes in and out of being mentally present. I think he wants to hold on to that.

Travis: This film deals with that time in our lives when we have these incredibly strong bonds with our parents. There’s a time in our lives when those things begin to shift and irrevocably change. These relationships change over time. That doesn’t mean they’re not powerful, it doesn’t mean that we don’t carry them with us as people drift out of our lives. Our experiences with the people we love — those are things we hold onto even when they’re not around.