Cultural criticism is hard. This is a statement that should be made in as plain and straight-forward a manner as possible. It is an awkward task, often thankless, demanding a gargantuan scope of knowledge and a focused sense of judgment. To be consistent, which is preferable, requires considerable quantities of introspection as well as philosophizing.

Then there is the question of the critic’s artistic achievement. They survey the expression of others, but as writers, critics struggle to develop their own artistic merit. If in the words of Jeanette Winterson, “Art is a dialogue, sometimes a shouting match, always an exchange” then a critic isn’t a good critic, a worthwhile critic, until they’ve added something artistic of their own to the discussion.

In other words, it is hard.

Harder still is the weaving of collected criticisms into a single volume. If the creation of a single review, a single essay of cultural insight, produces such challenges, how many more are presented by the gathering of disparate writings. What will the common thread be? What is the purpose of the collection, beyond merely compiling favored writings in a single place?

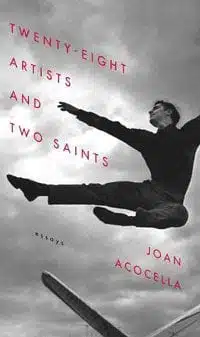

Such are the realities for Joan Acocella, cultural critic and staff writer for The New Yorker, and more specifically for her latest volume, Twenty-Eight Artists and Two Saints. To her credit, she’s aware of this and eloquent in addressing it.

“My concern is the pain that came with the art-making, interfering with it, and how the artist dealt with this,” she writes on the very first page. “Insofar as this collection of essays has a subject, that is it.”

This is the theme of Acocella’s book: “difficulty, hardship”, and not merely the boilerplate variety of childhood misfortunes or self-destructive addictions. Acocella focuses on the creation of the art itself, and the results are far more interesting than mere voyeurism. It’s rare for a work of collected criticism to coalesce into coherent argument, but here it does.

“There are many brilliant people,” she writes. “they are born every day — but those who end up having sustained artistic careers are not necessarily the most gifted.” Instead Acocella points out those who “combined brilliance with more homely virtues: patience, resilience, courage” delivered the creative goods.

There are exceptions to this, obviously. There are exceptions in this book. Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America is reviewed, he being the 26th artist in the collection.

Acocella writes in the introduction, “What allows genius to flower is not neurosis, but its opposite, ‘ego strength,’ meaning (among other things) ordinary, Sunday-school virtues such as tenacity and above all the ability to survive disappointment.” Such an argument is hardly supported by the inclusion of Roth, firmly entrenched in the most neurotic school of art, that of Jewish neurosis. Whatever difficulty and hardship Roth’s art embodies, it’s almost exclusively borne of the neurotic Jewish psyche he inherited.

“In Roth’s novels, relentless cautioning is usually done by parents. The sons, most of whom are writers, rebel, and produce comic novels about their elders. For this guilt, is heaped upon them,” observes Acocella in her discussion of The Plot Against America. She sees it as a sort of peace offering, “a novel about how the Jewish parents were right all along, a book about an American pogrom.”

Of course, Twenty-Eight Artists isn’t ironclad argument. It’s a theme that emerging almost organically and reflecting Acocella’s own philosophy: that genius alone is less significant than the pairing of talent and strength of character.

Moreover, the book remains a collection of essays drafted over the span of 15 years and intended, in their original form, to stand alone as criticism of single works of art. Philip Roth may not be a sturdy support beam for Acocella’s philosophy, but the essay on him is no less worthy of posterity. Indeed it is one the finest pieces of writing in the lot.

And it should be noted that the lot has considerable writing in it. If Acocella has made a claim to consistency in her voice, then she has shown an even greater capacity for literary production. Perhaps it is because she writes primarily about the art of dance, but there is a lyrical quality to the prose, spiked by an incisive wit.

On Joan of Arc — the second saint — and the voices in her head: “They told this illiterate peasant girl, who had never been more than a few miles from her village, to go to Orleans, raise the siege, and then take the Dauphin to Rheims to be crowned King Charles VII of France. In other words, they told her to end the Hundred Years’ War.”

On Mary Magdalene — the first saint — and her seemingly inconvenient role: “One wonders at first how it would help the Church’s chastity campaign for the first witness of the Resurrection to be a prostitute. But, as noted, the Church was pretty much stuck with the Magdalene.”

The writing is top-notch and the subjects are fascinating in their own right. It is thus surprising that the essay of greatest note deals with not an artist, nor a saint, but the most famous difficulty of creative types: writer’s block. It is of note mostly because it is so damned good, Acocella carefully picking apart the history, psychology, and cultural confines of the famed slayer of creativity.

“Writer’s block is a modern notion,” she writes. “Before, writers regarded what they did as a rational, purposeful activity, which they controlled. By contrast, the early Romantics came to see poetry as something externally, and magically, conferred.” With that we have a context in which to embrace or debunk the notion, and either way ultimately overcome it.

The British, it would seem, don’t put much stock in writer’s block. Good for them. Neither does Acocella, and in that case it is good for us.

The gift of Twenty-Eight Artists is that it represents the hard word of creativity in the embodiment of a critic’s perspective. Acocella is one of the best at such criticism, and the best description of this book is that it does on a larger scale what each of the essays does on its own: finds something coherent in the chaos of art.