Twin Peaks, the Original Series

It’s inarguable that television has become the major artistic medium in recent years. The best television has eclipsed both film and (sadly) the novel for cultural currency and quality. That we live in an era when our collective attention spans are punier than ever, and yet can doggedly invest in a television series over six seasons, is an intriguing contradiction.

Film can’t offer the same richly detailed characterisations that prestige television does. Nor can it present character development in the protracted way television shows do. Television programs are analogous to our perception of time. We perceive time in an episodic way, prone to digressions; sometimes we’re centre stage, and sometimes we fade into the background. Like television, our lives are less teleological than cinema. If a television series runs long enough, we can age in parallel with it. It can become the mirror in which we see our own life’s trajectory.

Possibly no contemporary television programme is more kindred to our experiences of ageing than David Lynch and Mark Frost’s

Twin Peaks, which aired in the early 1990s and was recommissioned, airing in 2017. Returning after a 25-year absence meant the characters had aged at the same rate as the viewer.

I remember getting a loan of a beat-up DVD boxset of the first season in the mid-oughts. I was discovering cinema and Lynch had just become my favourite filmmaker. The stills on the back of the cover, one with Audrey Horn’s (Sherilyn Fenn) unfortunate haircut from the pilot — thankfully her hair became very fetching in the second episode — didn’t inspire confidence and made the show look hopelessly dated. But surely

Twin Peaks would have to have some merit if it was made by the guy who directed Mulholland Drive and Blue Velvet?

Pretty soon, I was enraptured with a world that was both terrifying and strangely comforting; a world that, despite its seeming quaintness, contained multitudes. Twin Peaks is a show about a little hamlet, where the boundaries of reality are porous with other realms, where unseen forces are steering things — conveying a feeling we all have now and again. Though it embraces everyday comforts — “that’s some damn fine coffee” — it somehow seems to get at our deepest metaphysical hopes and fears.

And at the same time, it’s just a very entertaining, at times goofy, show.

Genuinely groundbreaking, Twin Peaks introduces surrealistic, avant-garde elements to the television landscape, while also indulging in, and playing with, the more formulaic elements of soap-opera television. This seductive brew hints at the potential that would later be realised in The Golden Age of Television, with prestige shows like The Sopranos, Lost, and Mad Men being inconceivable without Twin Peaks as their forerunner.

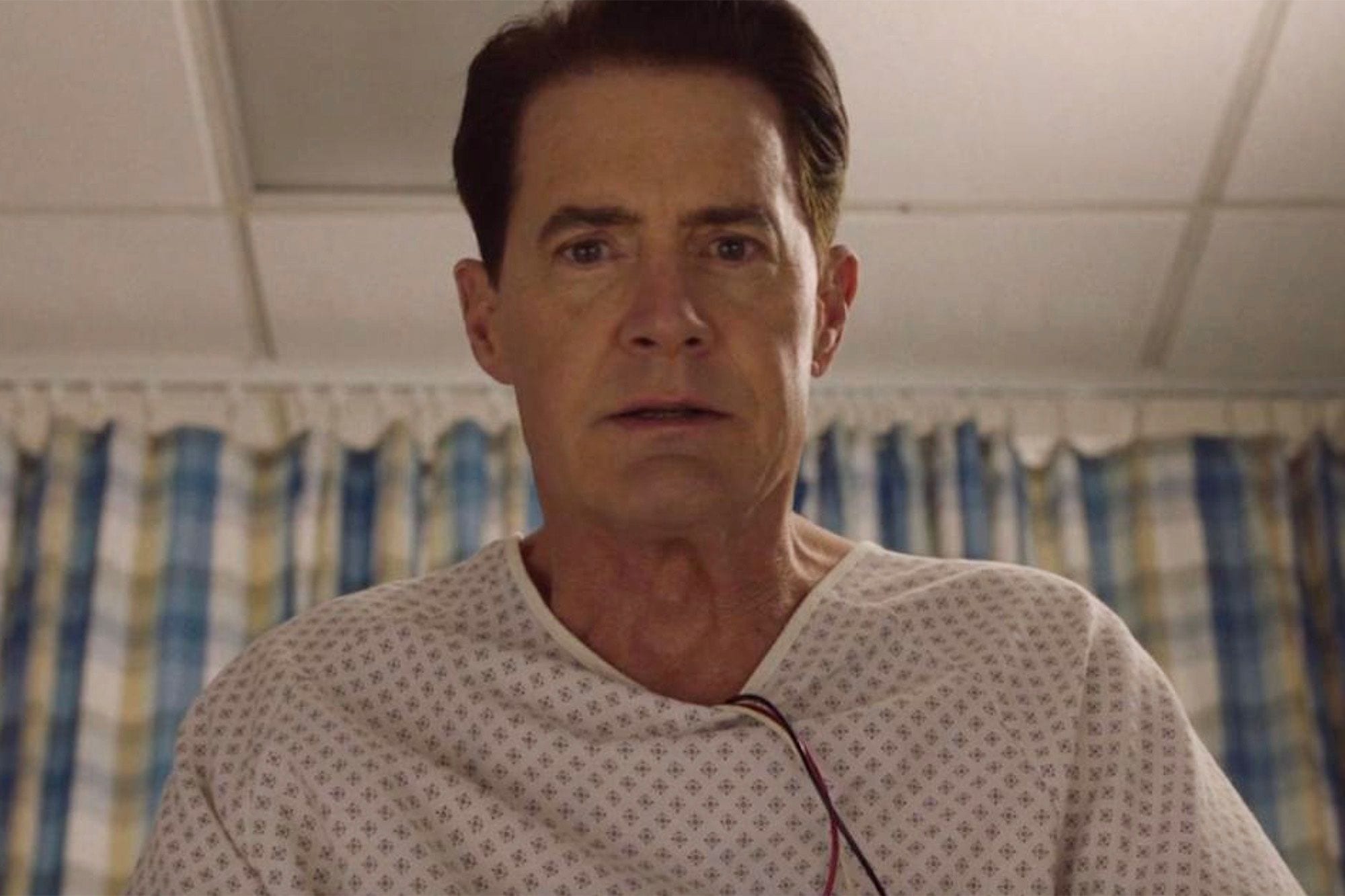

The story of the original run airing in 1990 had some of the same DNA as procedural cop shows and soap operas of the time. The homecoming queen, Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee), is murdered and Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan), a boyishly chirpy, yet noble FBI agent, who possesses a child-like wonder for the world around him, is sent to the town of Twin Peaks.

Through his investigation, we meet those who were close to Laura. Mystically-inclined, Agent Cooper is open to any leads, no matter how metaphysical their origin. In one of the most iconic episodes we enter Dale’s dream where Laura Palmer whispers the name of her killer in our hero’s ear. This takes place in the Red Room, a Bardo-like realm where our characters meet otherworldly entities and tussle with the dark side of their souls (embodied in a shadow self) before passing through to the next plane of existence. Here they meet their evil doppelgänger, whom they have to face with “perfect courage” or “it will annihilate your soul”.

What sets Twin Peaks apart from the usual mould is how avant-garde its sensibility can be. Agent Cooper gets clues from a dancing dwarf and a giant in a liminal dream zone, for crying out loud! Television audiences of the time were used to pap from shows like David Jacob’s Dallas. They weren’t accustomed to this kind of baffling fare. That said, Lynch’s co-creator, Mark Frost, a television writer later turned novelist, who definitely gets less credit for this show than he is due, more than likely helped things stay on course so they didn’t become too unmoored in Lynch’s ocean of pure consciousness, or as Lynch puts it, “the unified field”, where he believes all great ideas come from. Well versed in the language of television, Frost knew how to structure the show so that it would be green-lit by ABC, the risk-averse network that aired Twin Peaks in the ’90s.

Soon Lynch and Frost had a massive hit on their hands, with millions of viewers tuning in for each episode. That was until they ran into a problem: whether or not to solve the central mystery of Laura’s killer. Lynch wanted to keep the killer’s identity a secret, maybe forever, or at least until the last episode, but the lily-livered network, used to cookie-cutter television in which mysteries are solved within an episode’s half-hour and never sustained over entire seasons, bristled at the idea. Lynch knew that once the killer was revealed, the show would lose all of its suspense and intrigue, or as he inimitably put it in Chris Rodley’s Lynch on Lynch: “we had a little goose that was laying golden eggs, and they told us to snip its head off.”

Frost sensed the fans growing restless, thinking Lynch too absolutist in not solving the mystery. In a 2000 interview with Entertainment Weekly, he reflects on Lynch not wanting to reveal the killer: “I know David was always enamoured of that notion, but I felt we had an obligation to the audience to give them some resolution (…) That was a bit of tension between him and me.”

And so the killer is revealed, rather brilliantly it has to be said — but prematurely. An evil entity called BOB (played by Frank Silva) possessed Laura’s father, Leland (Ray Wise) — meaning she’d been repeatedly raped by her own father. It has been suggested that the BOB entity is thought up by Laura as a coping mechanism, and though the Twin Peaks storyline doesn’t exactly confirm or deny this idea, BOB is a very much an evil entity that has purchase over the minds of other people too, particularly if they are those supersensitive enough to other realms. Acerbic Agent Albert Rosenfield, played by Miguel Ferrer, postulates that BOB “is just the evil that men do”.

With this impasse between Frost and Lynch, fault lines developed in their once rock-solid creative bond. Lynch left Twin Peaks one third of the way through the second season, losing interest now that Laura’s killer had been revealed.

And boy did the show flounder spectacularly in his absence. A ridiculous, Scooby Doo-like villain called Windom Earle (Kenneth Welsh) is introduced, Nadine Hurley (Wendy Robie) develops superhuman strength, and things are just generally campy, and not in a good way. At this stage, the show is in the doldrums, with the viewership falling rapidly. It got moved to a different time slot — an indicator that a show is in its death throes.

Lynch had been right about the primacy of the central mystery. The network was going to cancel Twin Peaks but, with some arm-twisting from Lynch, ABC allowed Frost and Lynch to see the thing through to the end of the second season. Lynch would direct the final episode.

And then the unexpected happened: the final episode of season two, “Beyond Life and Death”, airing on 10 June 1991, became one of the best episodes of the series. Lynch revived the show with the defibrillator that is his boundless imagination. It was almost as though having nothing left to lose made him more ingenious than ever.

The season two finalé sees Dale Cooper enter the red room, now known as The Black Lodge, the realm from where BOB descended, to rescue his girlfriend Annie (Heather Graham), only for Cooper’s evil doppelgänger to escape, with good Cooper left trapped in the Lodge. And to make matters ten times worse, Bad Cooper (“Mr C”) is also possessed by the BOB entity.

This is deeply wounding. If BOB can possess Cooper, he can possess anyone. Or in other words, “the evil that men do” resides in us all. Laura is able to resist BOB, but she’s also in touch with her shadow side. Did this happen to Cooper because he hasn’t acknowledged his capacity for darkness? This is a very unsettling send-off to a show that’s destined not to be finished. Nevertheless, the lack of closure keeps it alive in the fans’ hearts for well over two decades.

The Unfairly Maligned Prequel, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me

Lynch was still haunted by his creation, in particular the character Laura Palmer. He wanted to make a prequel film, Fire Walk with Me, detailing the last seven days of Laura’s life. Things were becoming more strained between Frost and Lynch. Frost thought that a film should continue the story where they left off, so he didn’t have any involvement.

Fire Walk with Me is an extraordinary piece of work. However, it is ruthlessly uncompromising. We see the last seven days of Laura’s life, and it is incredibly disturbing. But there is also a great empathy to the story. Here Laura is a fully embodied person, not merely a device to make the show’s intrigue juicy. Laura is revealed to be a powerful messianic figure, whose light balances the darkness of BOB, who wants to possess her — Laura’s messianic status is confirmed in episode eight of season 3 when we see the Giant (Carel Struycken) making her and sending her to Earth as a reaction to the birth of BOB.

At first glance, Laura doesn’t appear to be much of a messiah. A contradictory figure, she helps the elderly by day and prostitutes herself by night in a coke-addled frenzy. There are times when her behavior is downright demonic. There’s plenty of darkness in her, but (and here is the crucial difference) it’s on a conscious level. She is actively engaging with her dark side, a necessary exigency for her to eventually counteract the darkness in the world.

This is the difference between Dale and Laura: Laura knows you have to concede that evil stirs within her/our own soul in order to conquer it, whereas Dale just wants to conquer it. Rather than be ensnared by evil she puts on a ring that weds her to the Red Room and then she dies. Understanding evil, in her mind, is the best defence against it. How often do you hear that a man who has killed his family was the friendliest neighbour on the street? Obliviousness to darkness means it can possess you more easily. Though strong-armed by a tragic fate, Laura retains her agency.

Fire Walk With Me was not fully embraced by fans. Very little light was shed on Dale Cooper’s fate, and the film was a commercial bellyflop and received no fanfare, probably due to how unflinching it is, the quirky tone of the show no longer present. In an article for Premiere magazine, David Foster Wallace wrote that he thought it was due to Laura’s twofold nature, claiming multiplex audiences want escape, and not this kind of moral ambiguity, as they feel implicated by it. In Twin Peaks, good and evil aren’t black and white. To Foster Wallace, Fire Walk With Me is a movie that requires that these troubling “features of ourselves and the world not be dreamed away or judged away or massaged away, but acknowledged.”

And that was that. Twin Peaks was dead. We would never discover Dale Cooper’s fate.

Or so we thought. In 2014, the most wonderful thing for Twin Peaks fans occurred: Lynch announced on Twitter that the show was coming back with a third season. Having matured and cast aside their grudges, Frost and Lynch got back to work, with Frost admitting that it was Twin Peaks‘ fervent fandom that kept the show alive in his mind.

The Return

Two years later, Twin Peaks finally airs in simulcast around the world. I feel a tingle crawl up my spine when I hear Angelo Badalamenti’s mellow and plangent theme tune.

And then it begins.

Initially, I was restless. Where’s the playful music? Where are the comic interludes and the soaring, soppy bits? The convivial warmth of the town’s folk is largely a thing of the past. The action is only partially taking place in the town of Twin Peaks, spanning many more settings.

And yet, there are many new treasures to behold. The new season’s pacing is glacial but in a hypnotic way, unfurling like smoke before our eyes. This slowness is entrancing. Our culture has sped up to a distressing degree, so to enter into a world with such a creeping pace at first feels peculiar, and then radical. The show’s pace is like a mystical old man who keeps a crowd rapt by his words, even though he’s not saying anything, really. Indeed, sometimes this slowness feels like a provocation — one scene is just a man sweeping for nearly three minutes.

Pretty soon, it becomes clear that Lynch is rewriting the rules of television all over again, giving us not what we want but what we need. For consciousness to be expanded, one has to ditch one’s formulas. Something deeper is happening here.

Initially, Cooper, everyone’s favourite FBI agent, seems poised to leave the The Black Lodge in exchange for Bad Cooper’s readmission. But Bad Cooper has a plan to foil this: he has made a Tulpa — a sort of clone — of good Cooper, who goes by the name Dougie Jones and lives in Las Vegas. When Cooper escapes The Lodge, it is Dougie who goes back in in his stead, and not bad Cooper. Cooper takes Dougie’s place in Las Vegas.

All this inter-dimensional travel, and the fact that his Evil counterpart still exists in the world, has rendered Cooper a brain-fried simpleton. (In Fire Walk With Me, David Bowie plays an FBI agent who lost all his agency and sense of time due to how discombobulating inter-dimensional travel is depicted.) Cooper (as Dougie) can only answer monosyllabically, and stares blankly at his loved ones in childlike incomprehension.

This seems like a further provocation to fans who just want to see Dale Cooper doing what he does best: being heroic and fighting evil. Instead, we are forced to sit through comic interludes as Dougie struggles to do banal tasks. Every so often, there are teasing glimpses of the Old Cooper — a look of recognition in his eye when he hears the word “agent”, cat like reflexes when attacked, and an insatiable thirst for coffee. Meanwhile, Bad Cooper is the one we find most interesting, and despite his mendacity, and blank, unfeeling nature, we sort of root for him, because at least he’s determined, albeit in a horribly self-serving way.

While I can sympathise with the bristling fans, I’m won over. It’s engaging to watch something so dementedly itself. I could never predict where anything would end up, with expectations defied at every turn. How can a show get anymore uncompromising? And then episode eight aires. But more on that later.

Though I too am longing to see Good Coop return to the town of Twin Peaks, it’s clear that something more interesting is being explored here with regards to identity. Cooper has already been bifurcated, and now there is a third Cooper. Cooper stands in for the audience, and being confronted with the fact that his identity can’t merely be that of an idealised hero is very disconcerting both to him and the audience. Just like Dr. Jekyll can’t help but be saddled with Mr. Hyde.

At many points throughout our lives, our identities bifurcate, as well: a job promotion makes us too big for our boots when really we know we’re the same heel we always were; family life mellows us but inside a raging ambition still stirs. Italian psychologist, Roberto Assagioli believed that within us there are “subpersonalities”, multiple modes in our psyches that are triggered without us giving the green-light. Say you become furiously resistant when someone tries to advise you, or you keep deferring to someone who seems intelligent, or, as is the case of Cooper, you have White Knight syndrome, so you try to right wrongs to an inadvisable degree. These “subpersonalities” are autonomous and need to be integrated or else they have the capacity to subsume our whole identity, particularly if they are disowned or unacknowledged. They are our way of dealing with challenges throughout the course of our lives, and at one point they did prove useful — that’s why they’ve remained — but they can thwart situations in which they are no longer appropriate.

Assagioli was heavily influenced by Carl Jung, who coined the term Individuation, which is the process whereby someone integrates all their unconscious parts (or “subpersonalties”), bringing them to the level of consciousness. He also came up with the idea of The Shadow, all those elements of our psyche that we reject. They can be negative characteristics, but needn’t be confined to this. Crudely speaking, a man who is excessively macho might demote his more affectionate side to shadow material, and might have compensatory dreams about cuddling lambs, or frolicking in meadows. In the case of Cooper, as Bad Cooper, he is experiencing his more self-serving side, and as Dougie Jones, his domestic, lackadaisical side. So both can be considered shadow sides, because agent Cooper is too noble to put himself before others, and too motivated to let himself enervate in family life.

If you think I’m barking up the wrong tree with these Jungian notions, author Mark Frost all but confirms it in describing Cooper’s arc: “From a psychological standpoint, you can say this is a guy who never integrated his ‘shadow self’ – I’m a Jungian, I believe in that stuff. David’s not psychological, he doesn’t even want to hear about it, but to me that’s what the story about.”

Resisting Nostalgia

So much time has passed that Cooper can’t remain the same, just like his viewer, who longs for the comfort of returning to a show to root for a hero with a fixed identity. Instead of trafficking in hollow nostalgia, the show takes the passage of time seriously.

When a beloved world returns, the creator often submits to mere fan service. The most recent Star Wars, J.J. Abrams’ 2019 The Rise of Skywalker, received a lukewarm critical reception because it kowtowed to irate fanboys, which meant it had none of its own flavour, and was just an expensive exercise in appeasement. Even Danny Boyle’s T2 Trainspotting (2017), a sequel better received, kept obsequiously referencing its iconic predecessor, rendering its own story nothing more than a sheepish addendum.

Twin Peaks: The Return refuses to be itself, and thus becomes even more itself, growing into something better and stranger. But wasn’t it ever thus? In its original ’90s run, the show refused to conform to its genre. What is this but ageing well? We should hope to be better and stranger by the end of our lives’ run.

Even though the show knows how to age, that doesn’t mean its protagonist does. A lot of growing up is accepting the unattainability of heroism, at least to the level of purity that Cooper aspires. Besides, to be a real hero in the real the world requires one to embrace darkness, which is impossible without embracing your own (à la Laura).

So, in Twin Peaks: The Return, this is the arc for both Cooper and audience alike — accepting that things have moved on. Cooper’s identity is atomised into three separate individuals. We long to see the Cooper we know and love, but for him to achieve the wholeness the maturation process dictates, he has to move on from being that former Cooper and become something different.

That’s not to say The Return is a tedious attempt to scold us for wanting the wrong thing, and depriving us of it. Lynch and Frost have enormous fun frittering away the season’s runtime, with Dougie’s miraculously charmed, marital bliss with his wife, Jayney-E (Naomi Watts) and son, Sonny-Jim (Pierce Gagnon). Cooper has finally been granted the simple pleasures of which he’s been deprived, having spent 25 years imprisoned in the Black Lodge. Nevertheless, somewhere in Dougie’s vacant head, our beloved agent resides. Good things keep happening to people Dougie comes in contact with. Even while practically lobotomised, there’s a kindness, a purity to Dougie, that is redolent of Agent Cooper’s essence.

By being replaced with the Dougie Tulpa, Cooper does get a happy ending, in a sense. However, the fact remains there are no endings, ever. Our natures are cyclical. In episode 16, Cooper finally wakes up. And it’s him, it’s really him, the coffee loving Agent with a heart of gold. And at last, the audience is given what they think they want. This means he has to leave this newfound family life to return to do duty in Twin Peaks. And when Cooper returns to Twin Peaks, he defeats evil with a little help from his lovable old pals.

But something is wrong. There’s something deeply amiss with this sequence. Closure has arrived in a conspicuously perfunctory manner. The way good vanquishes evil is far too neat. Lucy shot and killed the bad Cooper, without Cooper ever having to do anything. A deux ex machina character called Freddy, wearing a glove that gives him super-human strength, is the one who defeats BOB. These all feel like reminders of the unreality of what we are seeing. The biggest indication that something has gone wonky is that Cooper’s (a different Cooper) face looking overwhelmed is superimposed over the scene. “We live inside a dream,” this big face declares.

It appears part of Cooper’s identity is still in the Black Lodge, having gone so far beyond the human realm that time’s linearity has been revealed as an illusion.

Dreams and Reality

Just because a big superimposed head is saying that what are seeing is a dream, that doesn’t mean what we’re witnessing is moot, like a half-hearted ending written by an eight-year-old, so he can just go back out and play. The superimposed head could be drawing attention to the dreamlike nature of reality, that we are merely the dream of ourselves. Or, this timeline could be collapsing on account of Cooper meddling with the past. Or, more tediously, it could be a meta-commentary on the artifice of the show, and Cooper is now aware he’s a character on a television show.

Either way, in Twin Peaks dreams have just as much heft as reality, with which they are inextricably woven, and the same goes for our own lives. Dreams can point us where to go, or reveal to us something we’ve been overlooking. The invalidating of dreams is an unfortunate side effect of our more atheistic age. If anything, the reminder that something is dreamlike is more likely to draw attention to its significance rather than its lack of importance. If you fall in love in a dream, you are really falling in love. Dreams can feel, at times, more real than reality. Indeed, they can be a means of dealing with the surplus of reality we are dealt on a daily basis. So it follows that the more defensive the person, the more violent the nightmare. This material has to make itself known. This is why compensatory “subpersonalities” often show up in dreams.

Often people develop so many psychological defences over a lifetime that they get stuck in their development. Dreams are when these ego defences are suspended; that’s why it’s possible to wake up in mortal terror of mortality, as you spend most of the day in conscious thought just putting it to the side.

Nevertheless, dreams can also be emancipatory. There’s a beautiful scene in Season Two, in which Bobby Briggs sits down with his father, Major Garland Briggs. Up to this point, Bobby is depicted as a degenerate, two-bit hoodlum. His father tells him he had a dream about Bobby in the future, he’s happy and leading a good life. It’s one of those shining moments of goodness that’s in stark contrast with the evil present in Twin Peaks. To his son, Garland reports the content of his dream: “My son was standing there. He was happy and care-free, clearly living a life of deep harmony and joy. We embraced — a warm and loving embrace, nothing withheld. We were in this moment one. My vision ended. I awoke with a tremendous sense of optimism and confidence in you and your future. That was my vision; it was of you. I’m so glad to have had this opportunity to share it with you. I wish you nothing but the very best, always.”

And sure enough, Major Garland’s dream is bang on the money. In Season 3, 25 years later and long after his father’s death, Bobby is upstanding policeman who sadly accepts the dissolution of his relationship with Shelly. He accepts reality but doesn’t let that stop him from being a kindhearted father, and committed policeman. Redemptive arcs like Bobby’s are few and far between in Season 3. Bobby’s newfound upstandingness doesn’t feel like a cheap “aha” moment (so many characters in this new iteration of Twin Peaks are deteriorating morally, vacuously abusing drugs, joylessly conducting affairs, blindly going about their lives, the societal rot being the norm not the exception); we feel Bobby’s redemption was hard one, augured by that prophetic dream.

Bobby’s arc is in stark contrast to Cooper’s whose character development is put on ice, because he won’t leave well enough alone, and got stuck in The Lodge. People might balk at the idea of their beloved Cooper being arrested in development, and his character progression being compared unfavourably to the once avaricious Bobby. They might raise his innate goodness as a defence. But one can’t become self-realised through moral virtue alone. A martyr can never save more than the last person they’ve saved. So it is in the last episode of season 3, with evil vanquished, that Cooper, now equipped with supernatural, lodge-like capabilities, can’t resist going further, and sets out to reverse the past, specifically the death of Laura Palmer. He is incorrigibly upstanding in his purpose, his valiance giving him no sense of self-preservation.

Sure, Cooper is heroic, but excessively so. He accepts harsh realities for himself, but not for others. While more admirable than being in denial about himself, it still counts as not accepting reality. He’s hell-bent on being a saint. He’s so virtuous that he goes to monumentally self-sacrificing lengths to save Laura from her fate. It takes considerable hubris to bend the laws of nature, and this is exactly what Cooper does by going back to the night of Laura’s murder and altering events.

Another act of hubris so great that it tries to bend the very nature of reality occurs in episode eight – possibly the best and most groundbreaking hour of television that’s ever aired. We go back in time to 16 July 1945. We see a long sequence in which the first ever atomic bomb is detonated in New Mexico. We enter inside the mushroom blast for what feel like ages and are subjected to an onslaught of pure visual abstraction as Krzysztof Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima shrills over the score.

Cooper’s assuming heroism is like that of Robert Oppenheimer, the “destroyer of worlds.” The Trinity Test as part of the Manhattan Project in New Mexico was the single most destructive technology ever commissioned, therefore it is the most evil act of technological advancement ever committed. Splitting the atom is an act of scientific hubris on par — in storytelling terms — with going back in time and changing the course of history. To assume the power of a god seems to be where the human race is inexorably heading, the unremitting progress leaving no space for reflection.

No wonder then that in Twin Peaks: The Return, The Trinity Test tore a hole in the fabric of reality and unleashed the evil mother entity (Judy?) and its spawn BOB, whom is spewed out by Judy directly after the bomb goes off. These evil entities are inextricably linked to mankind’s most diabolical turning point. The world could never be the same again.

We then shift forward in time to 1956, New Mexico. Some very haggard and oil-saturated woodsmen descend from “pure air” and wreak their insidious havoc on a ’50s’era idyll. The leader of the woodsmen crushes the skull of the disc jockey at the local radio station, and recites a seriously unnerving poem over the radio that makes everyone in the community fall asleep. The very airwaves are subsumed by this evil. And it’s all deliciously creepy.

Elsewhere, earlier on, a boy walks a little girl home, those first stirrings of love evident between them. There’s a poignant innocence to their exchange: the boy behaves like a courtly gentleman; the girl finds a penny and hopes it will bring her good luck. Later that night, along with the rest of the town, the girl is put to sleep by the woodsman’s broadcast. A frogmoth hybrid breaks forth from an egg (presumably the same eggs that Judy spewed), climbs though her open window, and crawls into the girl’s mouth and is swallowed by the blamelessly slumbering girl. Evil has embedded itself. Frost later reveals that the little girl is Sarah Palmer, whose sin of omission with regards to her daughter’s later abuse is made more explicable by this origin scene.

There was an innocence to this post war period in America. In his memoir, Room to Dream, Lynch remembers his childhood in Boise, Idaho in the ’50s fondly, saying when he thinks of this time he sees “euphoric 1950’s chrome optimism”. But evil forces were looming and Lynch, an unusually sensitive boy, could feel it in the air. The ’50s-era veneer of goodwill, had a a dark underbelly, a reoccurring Lynchian theme. For all the mysticism and supernaturalism of Twin Peaks, Lynch and Frost still show that the world’s ills are always bound up with “the evil that men do”.

Not accepting reality is one thing, but changing the nature of reality is very much another. Scientific and technological progress are often unwisely thought of as ends in themselves. Jeff Goldblum’s Malcolm’s pithy line about bringing back dinosaurs in Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993) comes to mind: “your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should.”

In dreams, it is said that the reality of the dreamscape must be respected, too. Interference is terminal. Too much awareness of its dreamlike nature can send you back to reality with a jolt. In a dream, one is presented with a sort of reality, a psychological reality that wants to make itself known (but not too known). Still, there are people in the world — communities even — that try to lucid dream. Carl Jung was not in favour of this, he believed the dream images want to impart their ideas to you in a passive state, that you should respect the sovereignty of the dream’s content and not try to mould it to your will, that dreams may even be providing you with messages you register unconsciously. Hence, how sometimes we wake up with our worries feeling curiously resolved.

In Fire Walk With Me, Cooper enters Laura’s dream and tries to dissuade her from taking a ring that would wed her to The Lodge. He can’t surmise why her taking the ring is so necessary, as he’s too hell-bent on saving the damsel from her fate. White Knights always think they know what’s best for their seemingly helpless damsels.

The Realm of Ideas

Every Lynch fan knows the director uses Transcendental Meditation to “dive within” and come back with ideas. Much like dream images, these ideas are a law unto themselves, and have their own sovereignty. Hence, how rankled Lynch becomes when anyone asks him to explain his ideas. To Lynch, it’s almost as though they aren’t “his” ideas, but independent entities that he’s lucky enough to tune into.

One reason why Twin Peaks achieves such a profound depth is that Lynch’s work often dares to not know what it’s actually doing in terms of meaning and intent. As a result, it can often be a vehicle for bigger idea that occur by chance. Think of how a child can absentmindedly floor you with a statement of profundity. A child can also believe fully in the reality of an imaginary friend. Lynch’s consciousness is porous. There’s a purity to his creativity, not a trace of vanity. He doesn’t strain to have ideas. Ideas find him.

Lynch lore is full of the stories of the master shooting from the hip. In Mulholland Drive, having just exhorted filmmaker Adam Kesher (Theroux), to hire an actress as a lead in Kesher’s movie, a mysterious cowboy warns Kesher that how he proceeds next will determine his fate: “Now you will see me one more time, if you do good. You will see me two more times if you do bad.”

When they finished shooting the scene, Monty Montgomery, the actor who played the cowboy, asked Lynch how many times they would see the cowboy again.

“I don’t know. We will find out together,” was Lynch’s response.

Elsewhere, Frank Silva, the actor who plays BOB in Twin Peaks is initially just part of the crew, and is visible in a mirror’s reflection during one take. When Lynch is told this, it strikes him that Silva should remain in this scene, that he was meant to be in this scene. Thus, the scariest antagonist to ever grace the silver scene is born of out pure happenstance.

That the show came back after 25 years was foretold in the final episode of season 2, with Laura saying: “I’ll see you in 25 years.” By being open to randomness, Lynch and Frost have inadvertently made a prophecy.

Lynch plays fast and loose with both the script and with his overall intent. One can only laugh at Frost’s understandably vexed reflections of Lynch’s cavalier treatment towards the scripts he and others toiled over: “When [Lynch] got on the set, very often he threw out the script—which didn’t please me all that much.” This method of shooting from the hip more often than not works for Lynch because he’s guided by the ideas and doesn’t try to mould them for some tediously schematic purpose. His work is often seamless, but that’s because he never bothers to stitch his disparate scenes together. His films, often impossibly elusive, are nevertheless more alive for it and, at their best, seem to be a conduit for more meaning than if the story is pinned down from the start.

It’s like what Japanese filmmaker, Kon Ichikawa, says of his own work, that only long after making it and watching it with fresh eyes can he say: “Oh, so that’s what I meant.”

In one of the most moving scenes Lynch has ever directed, set in The Roadhouse, further examples of his intuitive ingenuity are demonstrated. Back at the Palmer residence, Leland/BOB is in the process of murdering his next victim, Laura’s cousin Maddy Ferguson (Sheryl Lee), in a terrifying and upsetting fashion. Unaccountably, those congregated in the Roadhouse seem to just pick up on the sadness of this event in the air, and start crying. One amongst them is, improbably, Bobby. Dana Ashbrook, who plays Bobby, just so happened to be hanging around the set, and Lynch said to him that he would be in this scene.

By and large, the death of someone is nothing more than just a plot device on most television shows. A Youtuber with the moniker Twin Perfect has put together a bravura four-and-a-half hour video (yes, you’ve read that correctly; I’ve watched it twice) in which he argues that Twin Peaks is an antidote to the consequence-free nature of television violence, and, whether or not you agree with him, there are striking insights along the way about media-consumption, the pitfalls of fandom, and creamed corn. Suffice to say, that Twin Perfect is able put together such a compelling thesis that seems largely valid is further testament to how open to interpretation Lynch’s work is.

Lynch is clearly a thoroughbred artist. In the aforementioned Premiere article, Foster Wallace marvels at Lynch’s indifference to how he is received: “David Lynch seems to truly possess the capacity for detachment from response that most artists only pay lip-service to: he does pretty much what he wants and appears not to give much of a shit whether you like it or even get it. His loyalties are fierce and passionate and almost entirely to himself.”

I’m sure its not easy to deal with a man who forgoes a set plan and a set schedule so capriciously — frayed nerves can be seen in a video of Lynch dealing with executives at Showtime. But rather than this indignation coming from rampant egotism, it comes from a sort of humility before the realm of ideas, which he treats with an almost religious respect, as though they are platonic forms. Lynch doesn’t try to covetously grasp them; rather, he sets the right conditions, and waits patiently for them to take his bait. Hence, his outrage when being told to hurry up his shooting. “I could have dreamed up all sorts of things up.”

He thinks of getting ideas like fishing, which he outlines in his book Catching the Big Fish.”An idea comes and you make it the way the idea says it wants to be, and you just stay true to that”, Lynch says of his creative process. This is why Lynch is so exacting on set: he’s trying to stay true to the ideas. Stymy his creative control at your peril; he still hasn’t fully recovered from losing creative control over the 1984 film, Dune.

For someone so irascible about ceding any creative control, it may come as a surprise to some how open to collaboration Lynch is, said tensions between Frost and he, notwithstanding. There’s always something even more important than his perspective: the realm of ideas. And it doesn’t matter where those ideas come from necessarily. He told Rodley in Lynch on Lynch, “when you write with somebody (…) it doesn’t matter who came up with what, initially. It becomes our stuff.”

Lynch’s receptiveness to ideas, no matter their source, means he’s open to some very troubling ones. People often puzzle over how dark Lynch’s work is. They can’t reconcile how terrifying his vision can be with his guileless, boy-scout demeanor. That said, when Lynch directs beauty he eclipses everyone else, too. The more you open yourself to darkness, the more you open yourself to the light. This is the salutary effect of accepting one’s own darkness. By seeing the ideas as autonomous, and as an end in themselves, Lynch possesses something of this radical acceptance necessary for character development.

Twin Peaks, The Ending

So that may be why the tone is so horribly realistic in episode 18, the final episode of Season 3. Reality has hit back at Cooper’s efforts to save Laura and has ensconced her in another timeline that looks conspicuously like our own. Have they entered the real world? That may explain why the atmosphere is so downbeat and alienated. In this timeline he has a new identity, Richard (identities collapsing and metamorphosing are lynchian mainstays).

Cooper is much less upbeat, still capable of virtue, but his methods are much more brutal — he shoots a guy in the foot who’s sexually harassing a waitress. It appears he’s integrated his shadow side, e.g., using aggressiveness to a positive end. When he finds Laura, who now goes by Carrie Page, she has no recollection of her former life. At this point, Cooper’s purpose proves intangible to both viewer and himself. It seems he is being led by vague hunches. He has taken it upon himself to make godlike decisions, his more human side is completely bewildered. There’s a cowed tentativeness to Cooper’s bearing, the sort that comes from the trauma of taking on too much responsibility. He is now fully in touch with the baffling nature of reality, a surfeit of reality. Still, he keeps striving but, like Philip Jefferies before him, he’s not quite sure where he is — or who he is.

He drives Laura/Carrie back to Twin Peaks. There’s a lonely, forsaken feeling as they drive back, a cavernous silence developing between them. When they reach the Palmer residence, the owner isn’t Sarah Palmer, but the real life owner of the house used in Twin Peaks, Mary Reber.

Eventually, Laura remembers some of what happened to her in the other timeline. Some trauma persists through time and space and there’s nothing anyone can do about it, no matter how heroic their efforts, except provide the victim a safe space to develop their autonomy around it. This is something Laura had already excelled at — intentionally sealing her own fate, and Christ-like, accepting it.

In the last moments, Laura remembers her life in the previous timeline. She lets out her trademark, blood-curdling scream. The lights in the Palmer residence go out, and the screen goes black.

So what the hell was that ending all about? Some fans were ruffled by this inscrutable conclusion. Here are some possible explanations we can posit:

1. Cooper managed to lure Judy into the Carrie Page timeline, because Judy feeds on pain and suffering, so Laura’s scream summoned Judy, and thereupon the timeline was collapsed essentially trapping the Judy entity, but also killing Cooper and Laura along with it.

2. Now that Cooper seems to have Bad Cooper in him, it could be that Bad Cooper took the reigns and brought Laura back to Twin Peaks to offer her up to Judy.

3. All of Twin Peaks was a dream, and Agent Cooper was a tulpa dreamt up by Richard as an escape from his cold, clinical life (I hate this idea).

4. Though appearing more psychologically integrated, Good Cooper is still misguidedly trying to put the world to rights, attempting to reunite mother with daughter. He still hasn’t learned the lesson that you can’t change the past.

5. The Carrie Page timeline is a dream, and when Carrie realises she is dreaming she wakes up back in the Palmer residence as Laura Palmer.

However, unless Lynch decides to make a fourth season, we’ll probably never know what the ending truly means. Not that another season would necessarily clear anything up. The ending might be insoluble by design. This means Lynch has the last laugh, for there is only one thing he hates more than meddling executives: narrative closure. By being unresolved the mystery of Twin Peaks prevails once more. So, just like in life, we have to surrender to the mystery of it all.

Is this an ending where good or evil prevailed? Or is it a stalemate? Or, for that matter, is it really an ending at all? This is the nature of character development. Losing innocence and being confronted with dark realities and uncertainty is never easy but it’s a sacrifice worth paying. Cooper is hellbent on carrying out his narrative closure. But in the real world we don’t often have that luxury. Laura understood this. Sometimes, we just have to accept our fates, something that doesn’t sit well with white knights. Carl Jung said accepting reality is ultimately medicinal.

By staying true to their vision, Frost and Lynch violently disabused us of our notions of what Twin Peaks ought to be, instead providing us with something weirder and more vital. Such can be our trajectory through life, if we can face hardship with acceptance and, unlike the fanboys, not be overcome with a lethal nostalgia for a mythologically better yesterday.

Sources Cited

Canfield, David. “Between Two Worlds”. Slate. 3 May 2017.

Foster Wallace, David. “David Lynch Keeps His Head”. September 1996.

Lynch, David. Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness and Creativity. TarcherPerigee. December 2006.

Lynch, David. Room to Dream. Random House. July 2019.

O’Falt, Chris. “‘Twin Peaks’: Mark Frost Takes Us Inside the Four-Year Process of Writing a 500-Page Script Over Skype With David Lynch”. IndieWire. 14 June 2018.

Quandt, James, ed. Cinematheque Ontario. Kon IchikawaKon Ichikawa. 2001.

Rodley, Chris. Lynch on Lynch. Faber & Faber. 1993.

Twin Peak Stories. “David Lynch – David Lynch Reacts To Time Contraints – The Set of Twin Peaks Season 3-Twin peaks 2017”. Youtube. 11 January 2018.

Twin Perfect. “Twin Peaks ACTUALLY EXPLAINED (No, Really)”. Youtube. 20 October 2019.

Uncredited. Mulholland Drive. IMDB

Various. “Frustration over Dougie”. Reddit. 2018.

Wallace, David Foster. “David Lynch Keeps His Head”. Premiere. September, 1996.

- 'David Lynch: The Art Life' Pulls the Garmonbozia Directly Out of the ...

- The Next Hot Music Scene Can Be Found at Twin Peaks' Bang Bang ...

- Why Does David Lynch Keep Doing This to Us? - PopMatters

- David Lynch's Lost Highway - PopMatters

- You May Not Get It, But David Lynch Knows What He's Doing in ...

- Room to Dream by David Lynch (book review) - PopMatters

- Will David Lynch Ever Make Ronnie Rocket? - PopMatters

- David Lynch's Dark Doubles: A Shadow Journey Into the Heart of ...

- David Lynch's 'Lost Highway Loosens' Our Grip on - PopMatters

- Moving Beyond the Dream Theory: A New Approach to 'Mulholland ...

- David Lynch's 'Blue Velvet' Covers the Darkness - PopMatters

- Ranking the Greats: The 10 Films of David Lynch - PopMatters

- Kathy Rain: A Detective Is Born - PopMatters

- It's 'Twin Peaks' Meets 'Nell'...Only Nastier!: 'The Woman' - PopMatters

- Mourning in America: Remembering 'Twin Peaks' - PopMatters

- 'Twin Peaks'?

- White by Northwest: 'Twin Peaks' and American Mortality - PopMatters

- 'Twin Peaks': Flame Wars, Walk With Me - PopMatters

- Twin Peaks: Down in Heaven - PopMatters

- 'Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me' Is a Semiotic Feast - PopMatters

- Retracing Classic TV With 'Twin Peaks the Entire Mystery' - PopMatters

- 'Twin Peaks' and Its Twisted Reflection - PopMatters

- Eraserhead - PopMatters

- Twin Peaks: Seasons, Episodes, Cast, Characters - Official Series ...

- Twin Peaks | Coming to Showtime - YouTube

- Twin Peaks (TV Series 1990–1991) - IMDb

- Twin Peaks - Wikipedia

- Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992) Trailer - YouTube

- Twin Peaks - Fire Walk with Me (1992) - Rotten Tomatoes

- Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992) | The Criterion Collection

- Twin Peaks - Fire Walk with Me: Kyle MacLachlan ... - Amazon.com

- Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me - Wikipedia

- Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992) - IMDb