When Paul Simon released his bestselling Graceland album in 1986, an international audience became familiar with the South African township music that had inspired Simon and that sent him to record in Johannesburg. However, while Simon’s album represented a commercial pinnacle, the ground for the international exposure of urban South African music was being laid elsewhere. The South African Gallo label had compiled numerous compilations of township recordings by the mid-1980s (Simon’s inspiration was one such compilation, the impossible to locate Gumboots: Accordion Jive Hits). However, Earthworks’ The Indestructible Beat of Soweto (1985) probably made the most impact on the international market (honorable mention should also go to Zensor/Rough Trade’s Soweto from 1982 and Earthworks’ Zulu Jive from 1984). For many listeners, this was the ideal opportunity to be exposed directly to the music, rather than hear it filtered through the essentially American aesthetic of Simon’s work.

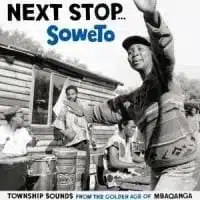

For anyone caught up in the epiphany of the Indestructible Beat album and its successors, the appearance of Strut’s Next Stop… Soweto, a three-volume project that kicks off with a compilation of mbaqanga music, is both an invitation to recall Earthworks’ groundbreaking work and an opportunity to reflect on the changes that 25 years of “world music” have wrought on the popular music landscape. It’s tempting to say that it is difficult to imagine a new compilation having the sort of impact that Indestructible Beat had because of the glut of anthologies on the market. But this would be inaccurate on at least two counts. First, there were plenty of compilations around in the mid-1980s. Secondly, there are doubtless a number of innovative anthologies covering emerging genres that will still have an important impact on certain sectors of society. It is just unlikely that a mbaqanga compilation will be one of those, given the genre’s association with the past — so many musical movements have come and gone in the intervening years.

But that’s precisely the point of imprints like Strut, Soundway, Analog Africa, and Now Again. The real difference between the 1980s and now is that the anthologists of world music are as eager to explore the recorded past as they are to document the unheard sounds of the present. Indeed, given the labor of love put into the practice of “vinyl archaeology” by these compilers (evident in the locating, contextualizing, and packaging of the music), they are probably more eager to do so. It used to be said of world music fans who had “emigrated” from rock, folk, and soul music that they went looking for the new in the far away. Now it seems that the new is to be found in the long ago. If the past is another country, then how far beyond the borders of what we know must the past of another country lie?

The exploratory tone is emphasized by Strut themselves, who speak, in their promotional material for this compilation, about “recent forays into Nigerian and Ethio grooves” (referring to their Nigeria 70 albums and releases by Mulatu Astatke) and promise to “take the listener far beyond the accepted township jive template”. The archaeologists who have exposed these musical fusions are Duncan Brooker and Francis Gooding, and their focus is on obscure releases aimed at the local market, which generally appeared on short run seven-inch singles. The featured artists are therefore likely to be unknown to the intended listeners of these compilations, though many will be familiar with the work of Simon “Mahlathini” Nkabinde and the Mahotella Queens, who appear here.

Mbaqanga (referring to a type of cornmeal or porridge but generally understood to mean “homemade”) was the name given to the type of popular jive music that emerged in the townships of South Africa in the 1960s as a development of the pennywhistle (or kwela) music of the 1950s. As kwelas were replaced with saxophones and new electric instruments were introduced, the musical template of mbaqanga was born. The vocal aspect of the music was distinguished by a development of earlier harmony styles and focused on the combination of call-and-response vocal lines, often featuring a “groaning” male singer accompanied by a female chorus (Mahlathini and the Queens being a classic example).

“I Sivenoe”, by the Melotone Sisters with Amaqola Band, serves as an excellent introduction to this selection, opening with a simmering electric guitar that, traversing the decades, wouldn’t sound out of place on a Tinariwen album, then setting a groaning male vocal against an instantly infectious female response team. The only disappointing thing about the track is that, like most of the songs on this album, it seems far too short, fading out before the three-minute mark. The upside of this is that, as each track disappears, listeners are quickly thrown into another few minutes of pop bliss. The Mgababa Queens dispel any dismay at the loss of “I Sivenoe” with the fresh brightness of “Maphuthi”, in turn giving way to the breezy instrumental “Kuya Hanjwa” by S. Piliso & His Super Seven. The latter track is reminiscent of the popular kwela instrumentals of the previous decade, except that the whistle has been usurped by the electrified sounds of keyboards, angular lead guitar, and driving bass. Accordion and harmonica are the dominant sounds of the Big Four’s “Wenzani”, though again the electric guitars keep the rhythm going as much as the percussion.

Mahlathini and the Queens are on fine form on “Umkhovu”, their interwoven vocal timbres given warm support by a chiming electric guitar that refuses to quit throughout the tune. “Zwe Kumasha” finds the Queens without Mahlathini on a track that takes its additional voice instead from a keening horn accompaniment. Zed Nkabinde’s “Inkonjane Jive”, with its honking sax, is a reminder of the R&B and jazz influences that were important to the fused sounds of mbaqanga. Tempo All Stars increase the horns with the brassy “Take Off”, the title of which could be interpreted two ways: it does sound rather like an imitation, but, then again, it does really take off in places.

The skillful interlacing of guitar and horn is heard to great effect on the instrumentals “Emuva”, by the African Swingsters, and the ska-like “Soul Chakari”, by Reggie Msomi & His Hollywood Jazz Band. And while any listener from outside of a particular music culture must be careful when comparing such music to more familiar styles, it is difficult not to hear an echo of the Byrds’ take on Bob Dylan’s “You Ain’t Going Nowhere” in “Jabulani Balaleli”, by Amaqawe Omculo. But where the whistles and whoops only add to this uncanny doubling, the massed voices (male and female) dispel any such speculation.

One of the great pleasures of this music is the way that the vocals are often delivered at a much slower pace than the dancing guitar lines; Piston Mahlathini & The Queens’ “Nomacala” provides an excellent example, the vocal lines dragged out in marked contrast to the song’s still eminently danceable overall sound. Even in such short tracks, there is much to listen for in terms of the variety of instrumental shades and rhythms. Many of the contributions are perfect miniatures, true nuggets of the pop past.

Next Stop… Soweto cannot hope to have the cultural impact of a record like The Indestructible Beat of Soweto. Contextualizing this music in the brutal situation of apartheid and in the era preceding the Soweto Uprising makes for a vital history lesson, but does not invite the kind of solidarity that the apartheid era compilations could. But that doesn’t detract from the importance of the new archeological work being done on the African popular past. These 20 tracks make for a frequently delightful anthology. Here’s hoping that the next two volumes — focusing on soul, funk, R&B, and jazz — will be at least as enticing.