You can easily imagine the characters in Ingmar Bergman’s devastating The Virgin Spring (Jungfrukällan, 1961) calling where they live “God’s country”. Their farm is situated in a kind of pristine wonderland of thick pine forests and gurgling streams. Religion plays a central role in most of their lives as well, with the mother, Mareta (Birgitta Valberg), seeming to spend her every waking moment in contemplation of God, and her husband, Tore (Max von Sydow), only slightly less fervent in his faith. They are certain of their place in the world, and God’s gifts to them.

The screenplay, by Ulla Isaksson, shatters that certainty with the force of a thunderclap. One of the few screenplays Bergman filmed but didn’t write himself, The Virgin Spring is based on a 13th century ballad about a raped maiden and the revenge enacted by her father. The first of Bergman’s many collaborations with cinematographer Sven Nykvist, the filming—the crisp black-and-white print rendered gorgeously in the Criterion edition‘s Blu-ray release—has an angular sharpness that also allows the beauty of the surrounding wilderness to shine through as an ironic counterpoint to the ugly story being acted out. His compositions carry a particular charge during the movie’s scenes of violence, one of which is carried out nearly on top of the camera lens, one man gasping his last while another quietly presses a knife into him.

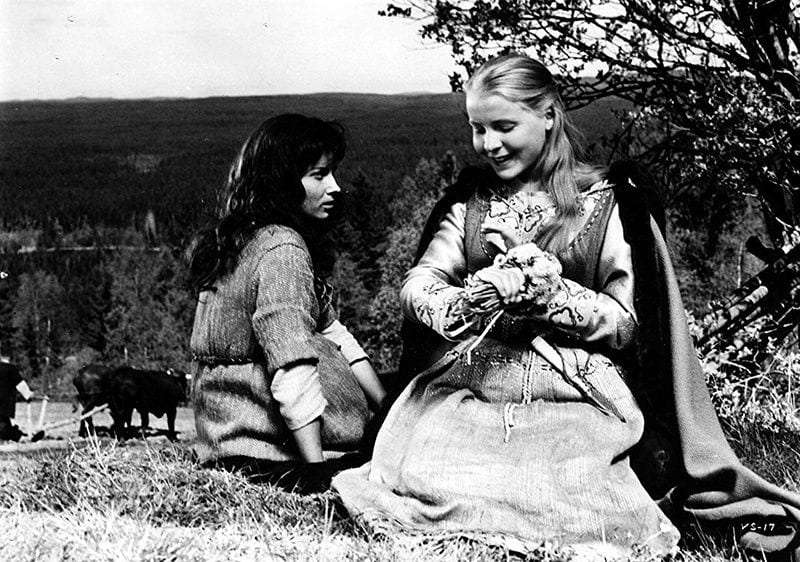

The dewy maiden at the center of this bloody gyre, Karin (Birgitta Pettersson), is presented as both the apple of her mother’s eye and something of a brat. While the family is up early, praying and working, Karin lies abed like any sluggish teenager. Still, Mareta is indulgent and filled with praise. No such generosity is shown to Ingeri (Gunnel Lindblom), their foster daughter and the put-upon Cinderella of the household. Dark-haired and rag-clothed compared to Karin’s expensive gowns and blond tresses, Ingeri seethes with resentment. In a devout Christian household, she is given the first words, “Odin, come!” Bergman purposefully positions Ingeri as almost some feral creature. “You are, and always will be, a savage child,” the servant Frida (Gudrun Brost) says. Ingeri is like the mythological artwork still adorning the household, as some throwback reminder of Sweden’s pagan traditions, which were just then being swept away by the beliefs of the converts, which are raging yet still new and shallow.

That faith gets its test after Karin is sent out on an errand, carrying candles to a nearby church. Along the way, she meets three goatherds. Happily soaking up the attention beamed at her from the two men and young boy in ragged clothing, Karin spins a teenager’s fantasy about her family, claiming she was a princess, not noticing the leering looks. After a gag planted in her things by Ingeri goes sour, the goatherds rape Karin. She dies after falling and hitting her head while trying to run away.

Not long after, the three appear at the family farm, asking for shelter from Tore, whom they assume is laden with wealth, and has no idea yet what they’ve done. Filled with Christian charity, and clearly puffing out his chest with pride at his own generosity, Tore lets them in. When he discovers what has happened, and sees what he is capable of in response, he is spiritually shattered and left shouting at the sky, “God! … You allowed it to happen. I don’t understand.”

This wasn’t Bergman’s first investigations of faith. Four years earlier, his breakthrough, The Seventh Seal, had set a new kind of standard in cinema for discussions of faith and fate. With its stark compositions and bleak reckonings with the cosmos, that movie also served as a kind of existentialist comment on the futility of faith. In The Virgin Spring, Bergman brings a narrower and more personal focus, not to mention a greater appreciation for humanity’s darkness. The movie contemplates larger issues, of course, positioning as it does the story at a dramatic hinge moment in religious history and seeing how new-found faith is tested by circumstance. A simpler tale than The Seventh Seal‘s symbolism-heavy fable but far more emotionally resonant, The Virgin Spring is Bergman’s murder ballad: Bloody, remorseless, and tragic.

In one of the Criterion extras, an audio recording of an appearance by Bergman at the American Film Institute in 1975, the director seemed mystified himself. Chatty and occasionally joking about his filmmaking process—”There is always some fool who wants to raise the money”—Bergman doesn’t pretend to have fully thought out his work. He compares it more to filming his dreams, coming close to saying that his art is just plugging in straight to his unconscious. Bergman refreshingly admits to confusion about what it all means.

But in many ways, The Virgin Spring is not difficult to comprehend. The story is reduced to elemental simplicity: Innocence, violence, more violence, sadness. The spiritual crisis that the previously pious Tore undergoes at the end is hardly confusing. What would make more sense than for a person of faith like him to question his beliefs, given the gulf between what he had been taught about the all-powerful and kindly God and his reality in which God might see but certainly does not act. The movie’s economy of storytelling and high-contrast visuals give it a noir-ish tint that might leave less room for the imagination to roam than the more questing The Seventh Seal. But the less-remembered The Virgin Spring is the better movie.