In an interview with Fab 5 Freddy on the new Wild Style: 25th Anniversary Edition DVD, one of many bonus features painstakingly collected by director Charlie Ahearn, the mouthpiece of old school hip-hop explains the story behind one of the film’s many memorable moments. In his typically charismatic manner the former Yo! MTV Raps host dramatically relays the dissolution of Funky 4+1, a group remembered for its prominent inclusion of a female emcee and originally slated to be featured in the film, over a record contract dispute.

As the story goes, two remaining members, KK Rockwell and Lil’ Rodney Cee, subsequently formed a new group, Double Trouble, and managed to retain screen time on the strength of a rap they personally delivered to Freddy:

Here’s a little story that must be told

About two cool brothers that were put on hold

They tried to hold us back from fortune and fame

They destroyed the crew and killed the name

The rhymes, which Freddy describe as “moving” for the lucid depiction of an artist biting the proverbial dust, appear in the film as an impromptu “Stoop Rap”, wherein the two emcees grind the axe in front of an anonymous residence. Ahearn films the scene with the unadorned look of a documentary, but with tight shots that enhance the tension. Fab 5 Freddy’s insight paints the scene as a close replication of the two emcees’ real-life angst over business shenanigans.

However, taking a cue from music theater, this well-choreographed sing-song verse (complete with a child who appears from nowhere to offer percussive accompaniment) flows seamlessly after a spoken rant. The fantastic aspect intentionally obscures the simple fact of the matter: these brothers are cheesed over having their paper fucked with.

Yet throughout Wild Style, Ahearn captures such overt interactions of art and commerce in the nascent hip-hop world with the wide-eyed wonder of the culture’s youthful innocence. And appropriately this “little story” has become one of the most sampled, referenced and prescient in hip-hop history.

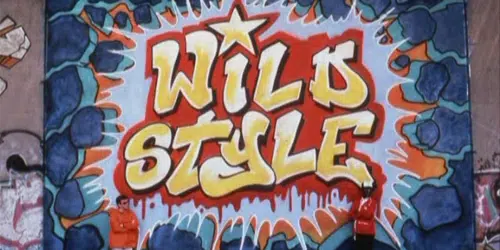

Revisiting Wild Style as a blueprint for hip-hop’s current materialism can be a disconcerting, practically sacrilegious effort. The hip-hop community treats the film (alongside Henry Chalfant’s bona fide graffiti documentary Style Wars) with a reverence comparable to what a religious community gives to a holy text. However, as is wont with such adulation, it becomes easy to take for granted.

Most agree that Wild Style‘s loose story of a graffiti artist’s rise to fame parallels and dramatizes what already happened when uptown sights and sounds found acceptance (i.e., underwriting) in downtown and beyond. But the film goes for the heartstrings with its depiction of protagonist Zoro’s (played by the well-cast elusive graffiti writer Lee Quinones, who hilariously recalls in a DVD extra his efforts to use make-up to mask his identity) awkward and reluctant feelings towards being “accepted”.

His eventual escape back to his “roots”, metaphorically depicted as the landmark concert in the Lower East Side Amphitheater, suggests that pure art can abstractly conquer all, whatever that “all” may be. But what is often forgotten in the haze of this celebratory climax is that Wild Style confirms what we now know for a fact: that hip-hop wanted to and succeeded in blowing up. This disconnect likely happens because no one in the Wild Style cast/ crew/ generation could actually conceive what it meant to go pop. In this sense, B.I.G.’s line, “You never thought that hip-hop would take it this far” sounds like a taunt.

The distance between Wild Style‘s vision of success and today’s standards are phenomenal. As the cast and crew make clear in the DVD’s bountiful extras, material rewards are overshadowed (admittedly not by choice) by respect and recognition. However, hip-hop in 2007 is impossible to discuss without considering global capitalism and capital worth. With millionaire moguls and internationally recognized celebrities staking out key positions in the face of the culture, hip-hop no longer preoccupies itself solely with its stature on the block.

As Greg Tate recently wrote, “if hiphop [Sic.] is now more defined by the corporate game than the street game, that lucrative little coup just might be the definitive hiphop act of 2007.” (“In Praise of Assholes”, Village Voice, 11 September 2007 So, what place is left for a little film that could like Wild Style?

The irony of such success is that the film and its generation must fight again to affirm everything it originally documented. In this sense, Wild Style seems more necessary now than ever — even than when it debuted in 1983. Fortunately, the normally low-key Ahearn has been heavily active this year with meeting this challenge. In June 2007 he released Wild Style: The Sampler, a companion book of photos and essays to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the movie. In the fall he and Fab 5 Freddy attended the VH1 Hip Hop Honors to receive recognition on behalf of the film. And, of course, he has finally completed the restoration of his most recognized work.

Occasionally, his responses have been predictable. In the humorous short Bongo Barbershop included on the DVD, Grandmaster Caz spontaneously trades rhymes with an emcee from Tanzania while receiving a trim and a fade, but the original Bronx Bomber repeats the mantra about his borough’s centrality in hip-hop history with the tired familiarity of a parent’s lecture. That said, Ahearn’s well-calculated publicity campaign has been the most effective approach — not to mention, a much-needed update in mass marketing the old school message.

Thankfully, Ahearn brings Wild Style to the present with more first-hand accounts than proselytizing. The bulk of his efforts, especially the film, emphasize the artist’s voice. Though the film is certainly an (amateur) exercise in acted performance, the DVD extras (commentary tracks, interviews with key cast and crew, entertaining shorts by Ahearn and clips from recent anniversary concerts) favor informal interviews or artistic expression.

Though many of Ahearn’s peers join the long critical chorus of contemporary hip-hop, seldom does he interject or editorialize (except for the aforementioned shorts). This suggests an important resolution: documenting the past, instead of enforcing it. With such a lack of airs, the line between “This battle we lost, but the war we’ll win” and “If they hate then let them hate and watch the money pile up” becomes clearer.