Walter Mondale coined the phrase Rust Belt during the 1984 US presidential election to describe the swatch of the Midwestern US plagued by the loss of industrial jobs in the last quarter of the 20th century. Mondale’s actual words were “rust bowl”; the press, recalling previous coinages such as Bible Belt and Sun Belt, adjusted his phrase to the term we’ve used ever since.

It’s a meaningful alteration. “Rust Bowl” of course echoes “Dust Bowl”: the temporary phenomenon that beset the American West half a century earlier, the result of a confluence of natural and economic disasters. The Dust Bowl has become the cultural, political, and photographic touchstone for the Great Depression. The New Deal helped the country recover from the Dust Bowl and the depression; an emphasis on governmental responsibility was implicit in Mondale’s choice of words, which he used in a criticism about the Reagan administration’s policies on trade.

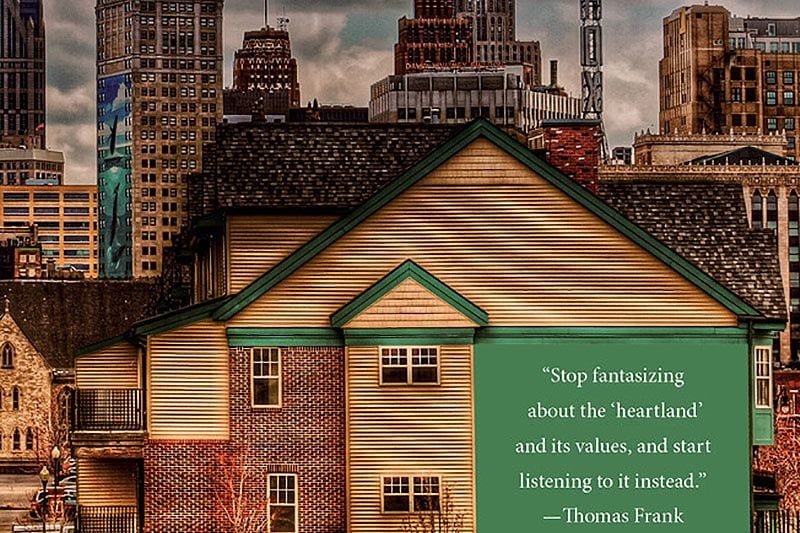

Rust Belt suggests a cultural and geographical region of long standing, like the dialect bands that stretch across the nation. Where Rust Bowl embraces progressive politics, Rust Belt is reactionary, a fitting phrase for the Reagan Era’s embrace of deregulation, victim-blaming, and racism.

Voices from the Rust Belt, a diverse collection of recollections, observations, and screeds by 24 writers, along with a short introduction by the editor, range between the “bowl” and “belt” poles. They were all previously published by Belt Publishing either in Belt Magazine or in books devoted to various cities in the region.

At times we get a glimpse of a way of life doomed to a drab, poverty-stricken sameness, at others an assessment of historical changes resulting from political and cultural decisions—some malicious, some mistaken; some pernicious, some promising—that invite action. Wherever they fall, the best essays combine the particularity of place and personal experience of memoir with the broader perspective of historical analysis.

Marsha Music, in “The Kidnapped Children of Detroit”, recalls the white flight from her Detroit neighborhood, both from the impressionistic perspective of the child she was at the time, and from the historically informed perspective of her adult self. The rapidity and secrecy of the departures gave the phenomenon a horrific aspect to young Music and her friends. How could families she had just seen in church pack up and be gone by Monday morning?

This view alternates with an even-handed assessment of the motivations leading white families to leave: racism and hatred, yes, but also the lure of the new suburbs and their promise of modern living. Music also details the practices like block-busting that, in Detroit and many other American cities inside and outside the Rust Belt, maintained segregation, or in the case of once-integrated neighborhoods like Music’s Highland Park, established it.

Music closes with a common refrain throughout Voices from the Rust Belt: a call for those trying to revitalize one or another Rust Belt city to heed its history and the lessons offered by “longtime residents”.

Amanda Shaffer’s “Bussing, a White Girl’s Tale” forms a nice complement to Music’s essay. Shaffer started high school just as court-ordered bussing integrated Cleveland schools in the late ’70s, and she started tenth grade as one of 20 white students in a class of 144. While she explicitly refuses to compare her experience with being black in white America, Shaffer expresses her gratitude for a chance to be a minority in her school. It opened her eyes to cultural difference as well as her family’s unquestioning racism, and led to her life-long dedication to “equity and racial and social justice”.

“It just happened” sums up the swift descent into poverty experienced by Dave Newman’s clients in “A Middle-Aged Student’s Guide to Social Work”. The 40-something master’s student is learning the ropes in a field placement in a Pittsburgh community outreach office that helps people in need find jobs or a place to stay, and provides groceries.

The essay mostly follows the travails of construction worker John, cheated out of months of pay by a contractor, in and out of jail, injured, angry and depressed, but always hopeful of finding work. Within view of the office is McKees Rocks, dead steel-mill town and boyhood home of OxiClean pitchman Billy Mays, who died of a heart attack brought on by longtime cocaine use. It’s a reminder of the seeming futility of Newman’s newly adopted profession: even the man who most famously got out and made it ended up succumbing to his demons.

Carolyne Whelan begins “King Coal and the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum” by tracing the life trajectories of two schoolmates: Wilma Steele, co-founder of the museum of the title, and Don Blankenship, chairman and CEO of Massey Energy in 2010, when an explosion at Massey’s Upper Big Branch mine killed 29 miners.

As she details the artifacts on display in the museum, Whelan lays out the complex and violent history of mining and unionizing in the region. The mine wars took place from 1910 to 1922, and the friction between mining companies and workers continues, although Steele explains that lately the coal companies have used strategic political contributions and investments to carry out a propaganda war far more effective than the one they once waged with hired guns.

Still, though Blankenship has been roundly vilified—he served a year in prison for conspiracy to violate mine safety and health standards leading to the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster—Steele, recalling how well liked he was in school, refrains from calling the man a simple villain. “Coal got him,” she concludes.

Blankenship is now running in the Republican primary for the West Virginia U.S. Senate seat currently held by Democrat Joe Manchin. It’s just one way in which Voices from the Rust Belt echoes today’s headlines: revitalization efforts; reclamation of parts of old industrial structures and transportation corridors; young, entrepreneurial people moving to Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo and other Rust Belt cities; malaise in the region that helped put Donald Trump in the White House.

This volume is full of lessons for anyone interested in American politics and the future both of the region and of the nation itself.