As travel itself has become democratized and accessible to more people, travel literature has receded into a specialized niche. After all, why simply read about someone else’s experience in a far-flung locale when you can have one of your own? This is a boon for travelers, but a loss for readers who, in prior decades and centuries, were routinely treated to what is now a rarity: travel writing by major literary authors.

Literary travel writing not only provides an attuned portrayal of the cultural exchange of travel and the intense personal significance often attached to our journeys, but it also tries to understand the rich context of these encounters. It can situate the reader in the immediate moment while also casting one eye beyond, to the history and mythology of the destination, unraveling the threads of past events that created the streets the traveler treads upon.

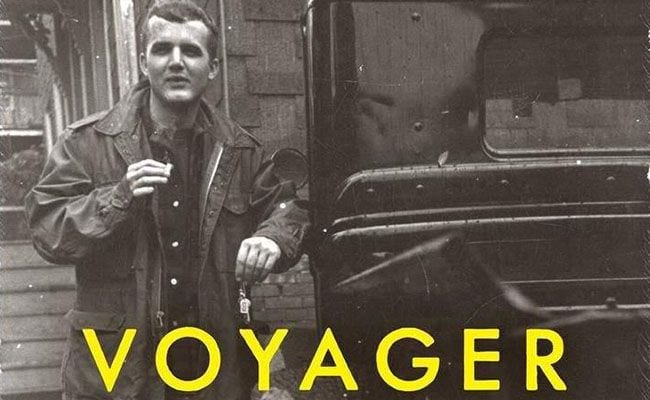

Russell Banks steps into this void with Voyager, his new collection of travel writing that consists of one novella length piece that traverses the entire Caribbean and shorter pieces on destinations including the Everglades, the Andes, Edinburgh, Senegal, and the Seychelles. Voyager is not of the moment — many of the pieces were written in years prior dating back to the late ’80s — and yet that becomes one of its main virtues, because Banks channels a throwback kind of author, akin to Ernest Hemingway, Graham Greene, or Peter Matthiessen (all referenced in Voyager) whose travels were an integral part of their character and writing. Banks never reaches the same heights of adventure as those men, but he is openly examining the same forces of dream and desire that drove those men to the ends of the earth.

In the title essay of Voyager, which takes up about half of the book, Banks and his girlfriend travel to almost every island in the Caribbean. As with many Americans, the region exerts a magnetic pull on Banks’ fantasy life and arouses longings “for escape, for rejuvenation, for wealth untold, for erotic and narcotic and sybaritic fresh starts.” For Banks, the Caribbean is a natural place to turn for a fresh start. As part of courting Chase, his soon to be fourth wife, he must tell her the story of his past marriages, two of which also drew him southward to the tropics, first in an ill-advised teenage marriage in Florida and then living and writing in Jamaica with his tempestuous second wife before she left him for a Jamaican.

The almost absurd idea of visiting every nation in the Caribbean leads to a fast pace, but also allows precise comparisons between islands that many too frequently lump together. Banks is able to quickly sketch the factors that forced certain islands down certain paths of development, including the different colonizers, the different island topologies, the different industries, and especially the toxic legacy of slavery and the plantation system.

The personal narrative that Banks intertwines is often interesting but also frustrating. While Banks is open and honest about his failures as a husband and writer, his failures in memory are somewhat more bizarre. Notably, he remembers traveling to Florida as a teen with romantic notions of aiding the Cuban revolution, only to reconnect with the gang-connected friend who had helped him with the trip and discover that he was actually staying in a boarding house (and here his memories are partially confused with the film Key Largo) with some of the right-wing spooks who planned the Bay of Pigs invasion. It’s somewhat shocking, both that a budding writer could be so unobservant at the time and so incurious for the many years after, but Banks skates by this fascinating period with little reflection in order to spend many more pages rationalizing failed relationships.

Occasionally the events on the periphery of the narrative are more compelling than what Banks focuses on. The connection between the travel narrative and the narrative of his past marriages is sometimes labored, but Banks is able to bring it all together at the end with an unexpected and poignant meditation on the Voyager space probe (he empathizes with traveling through the void at escape velocity) and a coda that all too briefly details his meeting with Fidel Castro.

While the title essay sometime drags, it does convey Banks’ character to the reader in ways that enrich the tauter pieces of Voyager’s second half. Banks interrogates the aging process first as a state of mind in “Pilgrim’s Regress”, which details a college reunion in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and the passing of the ’60s counterculture, and then in starkly physical terms in the collections’ three pieces about mountain climbing. Banks considers climbing both as a means of pushing physical limitations, but also as a spiritual activity, a parallel to prayer.

His gift for evoking landscapes reaches its greatest power in the sections on the Everglades and the Seychelles. He celebrates the Everglades as an almost prehistoric wilderness that’s closely rubbing shoulders with the rampant development of South Florida, and for embodying unknowable nature to such a degree that it can shift consciousness. To understand it, “you have to learn to switch your gaze from the concrete to the abstract, from the nearby riverbank to the distant sky. You need an almost Thoreauvian eye for detail and for the interrelatedness of nature’s minutiae.”

Many of the pieces show Banks in some of Earth’s last unspoiled wildernesses, a fact of which he is all too aware. (Banks frequently laments climate change, though he is also fatalistic about stopping it.) This strand of thought reaches its apotheosis on the Seychelles, a nation so paradisiacal as to be frequently compared to the Garden of Eden, but also so low-lying as to be one of the first casualties of rising oceans. Banks is lucky enough to see a paradise fly-catcher, one of the last known 80 in existence, and meditates: “Who was worth more to the universe, I or this tiny black bird? The answer did not cheer me.”

While Banks is not as peripatetic as the giants of travel writing or the novelists mentioned earlier (the travels in the book are all breaks from his more sedate life as a college professor), these essays show the extent to which travel has shaped his character, and even more important in a novelist, his imagination. Voyager is too short and varied to be a true classic of the genre, but it is effective literary travel writing. Banks evokes the personal feeling of his journeys as well as imparting the rich histories of his destinations and their possible futures. But as much as he expresses the specific virtues of each location, his greatest achievement is in evoking the enriching spirit of traveling itself, traveling without a destination, traveling as self-discovery, and reminds the reader that, at its best, travel writing is not niche, but it is large enough to contain anything.