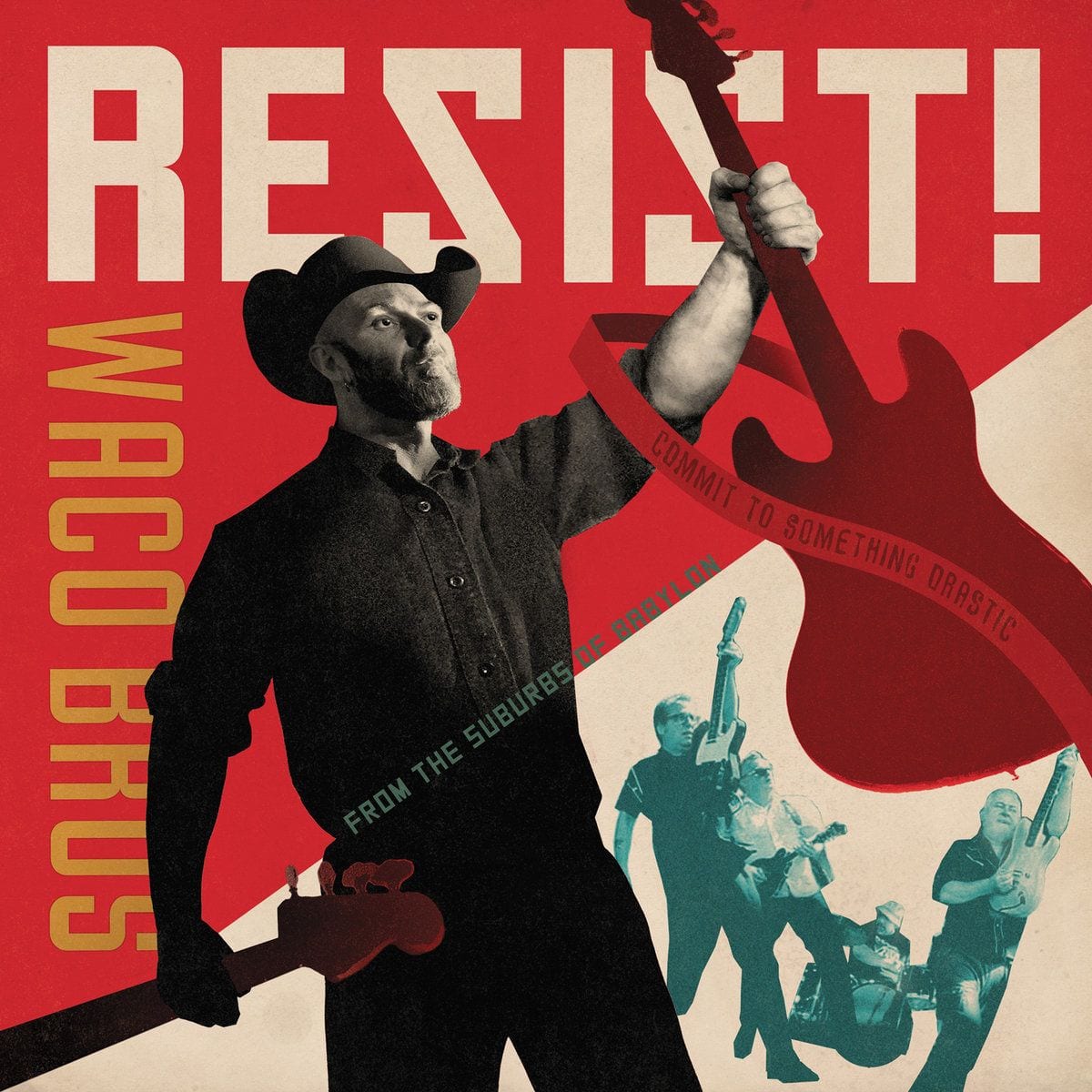

Resist! is the latest album from Chicago’s Waco Brothers. The album collects tunes from across the band’s 25-year-history, ranging from the political to the personal. The album opens with the clanging, clattering “Blink of an Eye”, reminding the listener of the collective’s full rock and punk power.

“Lincoln Town Car” presents the portrait of a man who has built the titular vehicle, only to watch a politician drive by in the same car. It’s both heartbreaking and true, demonstrating the power the Waco Brothers have to create images of the everyman that are potent today as they will be tomorrow and beyond. Despite its subject matter, the collection is far from dour. The anthemic “Plenty Tough, Union Made” elevates the mood, bathing the listener in a sense that better times are on the horizon while fortifying them with the energy to do just what the album’s title commands. A rousing cover of “I Fought the Law” doesn’t hurt either.

Founder Jon Langford spoke with PopMatters at the point when the United States was beginning to undergo a major shutdown in the wake of the Coronavirus: The band had hoped to make its way to South By Southwest but with the event canceled, plans quickly changed. Langford opened the conversation in a reflective mood, taking stock of whether plans for an impending tour would continue and what the remainder of 2020 would hold for himself and fellow musicians.

Throughout our conversation, Langford discussed social justice and his adopted hometown of Chicago, a place that has long been proud of the Waco Brothers.

Have you given any thought about what will happen if the Coronavirus stretches into six months?

We’re wondering how we’ll get through it. People could lose their houses. It could be that bad. If you’ve got no money coming in, I don’t know what you’d do. When you hear about it on the radio, most people are talking about it through the prism of the stock market. There’s nobody coming out and saying, “This is what you should be doing. This is the plan.” It’s very strange. You think they’d be talking about it in terms of public health or the people who are sick but its investors are losing their money. That’s the system we live in. Which is totally fucked! [laughs]

[laughs] I don’t have money in the stock market.

Me neither, so it doesn’t really matter but I guess if people don’t want to congregate in public places there’s not much we can really do.

You wanna talk about Resist!?

Yeah, it’s an album. You can buy it. It’s highly resistant to the Coronavirus. The music is so abhorrent no Coronavirus will attempt to get under your door.

I’m doubly blessed then because I’ve played it at the office and home.

You’re fine then. Nothing can touch you.

I’ll start with the obvious question: Why this collection of tunes now?

We have rude songs about every president since Reagan, since Carter. Songs come in and out of fashion for us when we play them live. But these are the songs that have become the mainstay of our set. The band’s been going for over 20 years. There’s a lot of angry political protest songs that we’ve made. We thought it would be nice to put them all together. We wanted to put them together on vinyl to put them into focus. A lot of them were written a while ago but the themes in them… it’s kind of worse now.

My understanding of human nature, as a child, was that we’re involved in this thing called progress and things are gonna get better. Social justice would improve and people would get richer and their standard of living would rise. Then you had Reagan and Thatcher. That myth doesn’t work anymore. I think a lot of songs are about that.

What was the first protest music you heard?

Folk music. As a teenager, I thought of Bob Dylan as older brother’s music, like I wasn’t smart enough to get it. But slowly it dawned on me. There was also reggae music. The vacuum of the progressive rock years was an interesting thing because that was almost content free. They were singing about elves and wizards. It almost had no bearing on daily life.

Then there was the Clash. Joe Strummer lived in my hometown in Wales and his nickname was Woody after Woody Guthrie. I think there’s a nice sense of balance there: In the middle of all the elves and wizards, play a million notes a minute, prog-rock ’70s, there was Joe Strummer thinking about Woody Guthrie and listening to reggae music, which was so political. I still listen to a lot of that roots reggae from the ’60s and ’70s. It was the music of the street in the mid-’70s in London and right through to when I left Britain.

Punk rock understood what reggae was doing and tried to find a music form that was their own that served the same function. They wrote songs that addressed immediate issues in everyday life. That’s what country music did for me as well when I finally got around to listening to that. The best honky-tonk music was music about working people.

What was it like during the time you were growing up in Wales? Was there a lot of economic strife?

When I was growing up, my town was a boomtown. It was a dock town, there was a big steelworks there and the coal mines were all working in the valleys above us. The town served the coal and steel industries. Working-class people were making money. The year I left, they shut Llawern Steel Works down to a third of its capacity in 1976. I moved up to Leeds. When I moved up to Leeds I saw the decay of industry up in the north. My town, Newport, has been going down the plughole ever since.

Britain in the ’70s, the picture in my head is all in black and white. The miners’ strikes, the three-day week, rolling power cuts imposed by the government. I think that fueled punk rock. There’s the Winter of Discontent where lots of people went on strike against what was essentially a socialist government. That brought Thatcher in and that’s when the social contract broke down.

The rich got richer and the poor got poorer, which has been the story ever since. The irony of working-class people voting for Donald Trump blows my mind. It’s like, “Wow. We are all fucking crazy.” I don’t understand how any would think that guy cares about anyone but himself.

It’s the political equivalent of prog rock!

I grew up in Michigan in the ’80s during a time of incredible economic strife. Bruce Springsteen released that album Nebraska and so much of it resembled the life we were living.

I don’t know if Dean Schlabowske took it as a compliment but I’ve always felt that there’s something about the way Nebraska works in his songs. I don’t feel like that’s my territory too much. There’s a lot of those songs on this album. “Lincoln Town Car” is about the guy who builds the car watching George Bush driving by in one. One that he’s built. It’s a conceit but it’s quite a good one. I really love that album.

When you came to the US were you already committed to being active politically and socially?

I didn’t realize how far out of the mainstream I was. My hometown in Wales is still being run by the Labour Party. We didn’t have the death penalty, we weren’t involved in the Vietnam War. I had traveled to the States a lot before I moved but actually living here and seeing and feeling the actual mood on the ground is very, very different. Somebody said that in Europe people look at rich people and while they may envy them and while they may want to get rich, they basically see the wealthy as dishonest because they know that what those people have they got by stealing and cheating to get it. That’s how we judged people, bottom line.

In America, it’s the American Dream thing is so pervasive. People admire rich people, they think, “Donald Trump is a smart guy. He’s played the system. But that’s what you do.” That sense of the communal well-being is totally undermined by this idea that anyone could become really rich and tell everyone else to fuck off. I felt that that was a major, major difference between the two societies.

Having said that, I think Britain has become much more Americanized. I was always very shocked by that, especially when traveling back. There were changes there that people might not have noticed but for me, it was in stark relief, how people emulated the style of capitalism that was going on here. Even the styles of capitalism everyone knew failed. They just let them happen: big box stores destroying town centers. I saw that in America when I first came over here. I never thought people would let that happen in Britain.

The main street in Newport is just charity shops and tattoo parlors mostly. Everybody gets in their car and drives to a big box store. They let that happen. It’s a process of disintegration.

Those big box stores are only going to be around until Bezos finally figures out how to fully crush them.

You go to the malls in Chicago and they’re completely rundown. They built these palaces of commerce and now they don’t go. I’m sitting behind a Fed Ex truck now in my car. There’s Fed Ex and UPS trucks going everywhere, shitting out their greenhouse gasses.

People always ask me why I’m a socialist and it’s because you need a plan. You can’t just have capitalism going mad and wherever the money goes you follow it. Or you end up with what we’ve got now. The environment is on the brink. Health services are incapable of dealing with an approaching pandemic. Because everybody’s just been fucking following the money.

I was born in 1957 and there were people of my generation who were wowed by the idea that some guy started a multi-national corporation in his garage. It was like they didn’t realize that people like that already had some money. They weren’t like the rest of us.

I’m a socialist because I don’t believe in inherited wealth. I believe in leveling the playing field. But that’s gone out the window now. It’s like talking about alchemy, the idea that we might have fairness in society and that our leaders wouldn’t come from the most entitled and privileged backgrounds. But that’s what you’ve got in Britain now. Boris Johnson’s probably not even competent to do the job but his breeding and background, people buy into that. It’s safer to have someone who is an upper-class twit straight off Monty Python running the country because he was born to rule.

You’re catching me on a bad day. [laughs] The songs on the album express quite a lot of these ideas.

What is it about Chicago that makes it home?

Of all the American cities it’s the one that feels the most comfortable. It has a feel of the north of England, where I lived for a long time. I spent a lot of time in Leeds but that’s very close to Manchester, which was culturally hugely important as an alternative to London during the punk rock years. I loved the attitude of people in Manchester. They didn’t give a shit what people were doing in London. They were self-contained and confident.

When I came to Chicago I got a feel of that. People in Chicago are oblivious to what’s going on in L.A. and New York. They just don’t care. Most of the record label people and journalists and fellow musicians seemed to be just doing it out of a genuine love of it. It wasn’t like this career path and money grab.

I didn’t know what I’d do when I got here but there was a river that moved me along. I got off the plane and was in the middle of something. It was fantastic.

Do you feel the urge to write more protest songs?

I can’t help it really. The songs pick you.

Photo: Paul Beaty / Courtesy of Bloodshot Records