Baking is more science than art, even the most uninitiated can tell you that. With its precise measurements, specific instructions, and detailed order of preparation, what appears deceptively simple in its final form actually masks a laborious path of creation. Any baker knows that be it simple chocolate-chip cookies or elaborate gourmet cakes, the opportunity for disaster is ever present. A pinch too much of salt here or a teaspoon too less of sugar there and your sweet treat can quickly turn bitter.

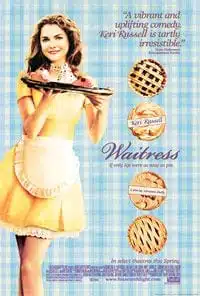

As it turns, out the culinary arts are not that far removed from the cinematic, as both seek to push forward on that tenuous line between well-crafted indulgence and ruinous excess. A more literal exploration of that metaphor can be found in Waitress, a small independent film that made its debut at Sundance in 2007, that explores (among other themes) the delicate balance needed to achieve the perfect desert.

Blessed with a talent for baking and saddled to a life without much hope or promise, Jenna (Keri Russell), a small-town waitress, finds both solace and freedom in the kitchen. With a lovingly obsessive devotion to her craft, Jenna directs all of her creativity, hopes, dreams, and frustrations into creating unique pies — with catchy names like “I Don’t Want Earl’s Baby Pie” and “The Naughty Pumpkin Pie”. Stuck in a marriage to Earl (Jeremy Sisto), a boorish and violent speck of a man, Jenna dreams of escape and views her pie-making talent as her ticket to independence.

However, Jenna’s dreams of running away are quickly hampered when she discovers that she is pregnant. Regardless of her hatred for Earl, and her total disinterest in having a child, Jenna never once considers terminating the pregnancy. Instead, resigned to her fate, she returns day after day to the humble diner where she works and bakes her pies. While her home life is in a constant state of flux between indifference and violence, Jenna is able to find support from her co-workers at the diner, Becky (Cheryl Hines) and Dawn (Adrienne Shelly), and the lovingly cranky old owner, Joe (Andy Griffith).

An additional and unexpected source of comfort and excitement comes into Jenna’s life when she makes an appointment to see her gynecologist and is surprised by the presence of a new (very attractive, very male) doctor. Freshly arrived from Connecticut and fumbling over his own awkwardness and the small town’s charm, Dr. Pomatter (Nathan Fillion) instantly takes a liking to both Jenna and her delicious home-baked creations. The fact that both he and Jenna are married — not to mention that she’s pregnant and he’s her doctor — proves incidental to the two of them and they quickly strike up a passionate affair.

Maybe it’s all that sweet Southern air wafting languidly throughout the movie, but such complicated ingredients only serve to heighten the confectionary delight that Waitress strives to be. As throughout the film, instead of playing up the drama and tension within this narrative strand, these plot points are viewed through a candy-colored lens that quickly removes any astringency or bitterness. Tempered sanguinity and humor in the face of Jenna’s challenges would be understandable, but too often Waitress feels drowned by its heavy dusting of powdered sugar.

For all the baked-in sugary sweetness evident in the movie, there is a silent and uncomfortably tragic air that hovers over Waitress. Just prior to the film’s theatrical release writer, director, and co-star Adrienne Shelly, age 40, was murdered in her New York apartment. While the film had already been finalized and edited under Shelly’s supervision, it is difficult not to approach the film and, especially, its final scenes, without a certain sense of wistful sadness, which is probably far removed from the hopeful tone the filmmaker was trying to establish.

It may seem indecorous (and it is certainly unfortunate), but the audience’s experience of Waitress is both enhanced and confused by the terrible circumstances surrounding the film’s director. Adding further to the movie’s (real-life) bittersweet mixture is the fact that Waitress, for all of its shortcomings, is a real showcase for Ms. Shelly. The film reveals her talent and promise as a unique, curious, and refreshingly lo-fi voice in the American independent film landscape. Sadly, that voice and her vision will never have the chance to expand further.

Waitress will almost certainly find a larger audience on the home video market than it did in theatres. The film’s easy pace and distinctive temperament feels better suited to the small screen, where the comforts of food and entertainment are already well established. Along with the standard issue of “extras” (i.e., behind the scenes footage, press junket interviews, commentary, etc.) the film’s release on DVD also includes a brief tribute to Ms. Shelly.

While Waitress is by no means a great piece of cinema, there is a certain determined optimism and quirky charm that rescues the film from its own buttery premise. Waitress is a fine treat to satisfy your sweet tooth — just bear in mind that you may exceed your daily recommended dose of sugar.