Of the five animated shorts nominated for an Oscar this year, only one is “hand drawn”. i>Persepolis, nominated for the animated feature award, is only the seventh “drawn” cartoon to be nominated in that category since the award was established seven years ago. Today, the preferred method of animation is digital, as Pixar and other computer oriented studios dominate the field of animation, except, of course, in the area of anime.

Reviewing the five Oscar nominated shorts, Stephen Holden of The New York Time noted the shorts’ “sophisticated illustration” and the “digital wizardry” which had led to an “astonishing creative revolution”. (“No Mickey Mouse Stuff”, 15 February 2008) Mr. Holden’s favorable impression of the shorts is justified, but the true astonishing creative revolution occurred 70 years ago.

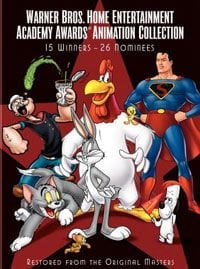

The cartoon work of the ’30s through the early-’60s was sophisticated for its day, and its creativity and vibrant illustrations are as wonderful to behold today as they must have been decades ago on the big screen, dwarfing anything generated by a computer. Warner Brothers has collected 41 such masterworks into one collection, the newly released Warner Bros. Home Entertainment Academy Awards Animation Collection . On the three DVD set are 15 Oscar winners (14 for Best Animated Short and one for Documentary Short) and 26 nominees.

Disney aside, no collection of cartoons better represents the history of popular animation. The set features many of the characters you grew up watching if you’re over the age of 25: Bugs Bunny, Foghorn Leghorn, Tom and Jerry, Superman, Popeye, Porky Pig, Droopy Dog, Tweety and Sylvester, and more. Off-screen, some of the era’s best worked: Carl Stalling’s music, Chuck Jones’ zany jokes, Hanna and Barbera’s characters, Mel Blanc’s voice-overs. The cartoons here show the work of these master animators at top form.

Those familiar with these cartoons will most likely know them from Saturday morning and afterschool kid’s shows. However, such familiarity does not guarantee that one truly knows these cartoons. Washed out and scratched, the television airings paled in comparison with the remastered originals. One is immediately struck by the vibrant colors and exquisite detail of the background art. It is also pleasant to see the cartoons in full-length, as many were cut to fit between commercial interludes.

Watching the cartoons in a package also highlights the science-fiction emphasis prevalent in early cartoons. In a time before CGI and Industrial Lights and Magic, cartoons offered the best means of escaping to alien worlds and envisioning what awaited us in the cosmos. The first cartoon of the set, ’40s “The Milky Way”, shows an imaginary trip by three kittens through the Milky Way, which, ideally, is filled with actual milk. “Popeye the Sailor Meets Sinbad the Sailor” features the muttering sailor and gang travelling to a land of two-headed monsters and other frightening creatures.

While these cartoons are playful and children oriented, 1939’s “Peace on Earth” and its remake, 1955’s “Good Will to Men”, are just frightening, offering an apocalyptic vision of how mankind eradicates himself through constant war. “Peace on Earth” features an elderly squirrel recalling the tale of man’s self-destruction for his grandchildren, relying on deco-stylized images of tanks, troops, and destroyed cities to convey the horrors of war. “Good Will to Men” keeps the same artistic style, but has the added element of nuclear holocaust (and changes the squirrels to mice). The immediate impression is that this is hardly suitable fare for young children, but the cartoons have a moral lesson to teach: humankind’s demise is directly linked to its inability to heed the lessons of the Bible. It is a hell-fire and brimstone sermon beautifully wrapped in an artistic package.

Other cartoons also provide life lessons. “So Much for So Little”, 1949’s Oscar winner for Documentary Short, is a propaganda piece promoting the important work of the health department. “Blitz Wolf” (1942) shores up the argument for entering the war, as the three little pigs battle a Hitler-looking wolf. On a more abstract level, 1965’s winning “The Dot and the Line”, perhaps in response to the growing counterculture, preaches a lesson that conformity is good, and hard work is rewarded.

The true value of the DVD set lies not in its lessons though, but in its record of the growth of animation between the late ’30s and mid-’60s. Art in animation has followed the direction of fine art, moving through stages of realism and various styles and color influences, and these stages are clearly on display here. Earlier cartoons are more idealistic, with soft, rounded figures and angelic choirs often providing background music. By the late ’40s, cartoons had become much more silly, slap-stick escapism for the new nuclear age. The cartoons of the late ’50s and early ’60s are less likely to follow a plot and more minimalist and avant-garde in their artwork.

For instance, “The Dot and The Line” tells of budding romance between a line that learns to make shapes and a dot. Chuck Jones’ “High Note” (1960_ deals with the ways in which a drunk note disrupts a sheet of music, while his abstract ’62 classic “Now Hear This” shows what happens to a proper British gentleman who accidentally uses one of the devil’s horns as a hearing aid.

The DVDs also feature voice-over commentary for 14 of the cartoons. How interesting these comments are depends on the source and one’s personal interests. Historian Amid Amidi provides notes about why “Now Hear This” strayed so far from the look of most Jones cartoons (Jones allowed newer members of his staff control the look and sounds of the piece). Director Erik Goldberg’s comments about “Cat Concerto” initially dealt with the Oscar controversy before digressing into a discussion of which animator drew which segments of the cartoon. Those interested in the historical aspects of the cartoons will likely be more intrigued by the background information on the shorts, while fans of technique will be drawn more to commentary about individual artists and styles.

Additionally, six of the cartoons have a music-only audio track option. Many of the cartoons are equally enjoyable sans the dialogue and sound effects, and this option allows viewers a different way of watching those cartoons that are primarily action.

Still, the DVD set has its limitations, in that it is restricted to Oscar nominees and winners, and the Oscars haven’t always been known to make the best choices. For instance, two Bugs classics, the opera parody “The Rabbit of Seville” and the hallucinogenic “The Big Snooze”, failed to be nominated and are thus excluded from the set, while the repetitive “Tom and Jerry” series was racking up Oscars, winning every year from ’42 to ’46, and thereby dominating the first of the DVDs, which features only winners. While “The Cat Concerto” (1946) is arguably the best of the series, it lacks the originality of the ingenious “Snooze”.

However, the commentary provided for “The Cat Concerto” provides insight. Upon realizing that Merrie Melodies was producing a Bugs cartoon almost identical in plot to “Concerto”, Hannah and Barbera rushed “Concerto” into theatres. Academy voters assumed that “Rhapsody Rabbit” was plagiarized, and awarded “Concerto” while ignoring both “Rhapsody” and “Big Snooze”.

For those who grew up watching these cartoons, this collection is a treasure; for those who grew up watching Smurfs and My Little Pony, this is a chance to have a fun and funny history lesson. The days of Saturday morning cartoon shows have fallen prey to political pundits and Disney’s latest efforts to create another teen princess to fill our tabloids. And the Cartoon Network has no sense of pedigree. Consequently, collections such as this become even that more valuable, a chance to enjoy some of our greatest animation.