It’s no surprise that a recent edition of Zhuangzi’s The Way of Nature, an ancient Daoist text, was a best-seller in China—where roughly 12 million people identify as Daoists. It’s perhaps a little surprising that the edition was a comic book. Now thanks to Princeton (a press not typically regarded for its line of comics) cartoonist C. C. Tsai’s adaptation of The Way of Nature is available for the first time in English.

Tsai (his first name is Chih-chung, but he prefers C. C. when publishing in English) is already well-known to Asian readers, and hopefully, that well-earned acclaim will translate to new audiences. If you know as little about Daoism as I do, you don’t recognize the name Zhuangzi, either—though apparently, he’s right up there with his better-known Confucian forebear Confucius. Tsai provides an ideal introduction.

Tsai’s layout is elegant. Built around consistent two-page spreads, each left-hand page opens with a full-height caption box containing Zhuangzi’s original Chinese text, and each right-hand page closes with the same. The caption boxes never vary in size, but the amount of writing does, with as much as six full columns of Chinese ideographs and as little as one. While I can’t read Chinese, I appreciate the choice on the general translation principle of providing originals and, even better, how well Tsai integrates them with the translated content sandwiched between.

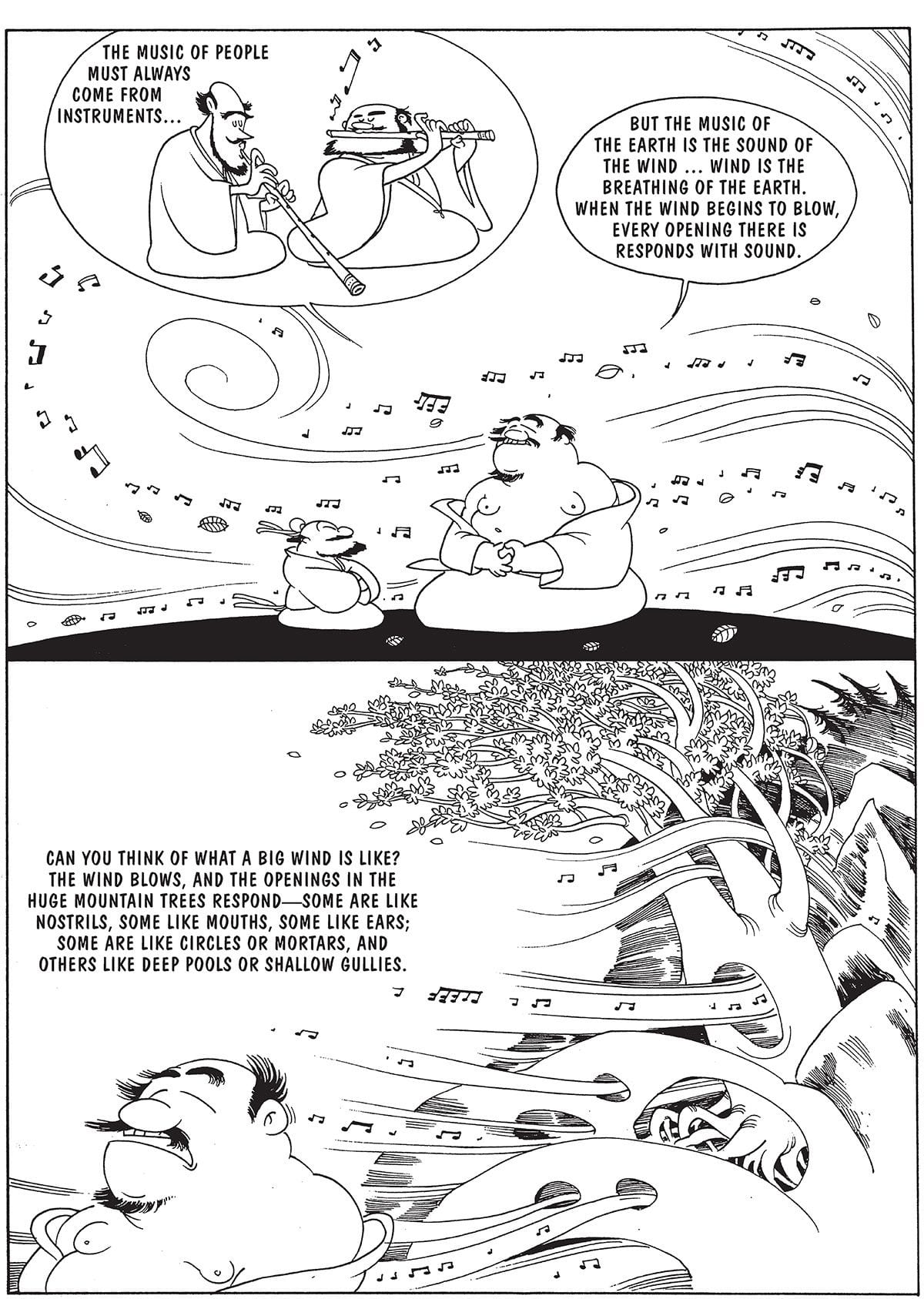

Tsai also uses the columns as a visual element, with the lines that compose the ideographs echoed in the cartoon sections between them. Gutters separate the caption boxes, but adjacent comics frames are interconnected with single lines defining each set of panels. It’s a subtle effect, but the choice compresses the multiple panels into single ideograph-like units. The interiors of the panel are sparse, with the English text floating freely in negative space that merges with the mostly undrawn backgrounds of the cartoons.

(Courtesy of Princeton University Press)

The thin black lines of the drawings, the English words, the frames, and the ideographs all combine in balanced compositions well-suited to the themes of Zhuangzi’s writings. Such sage advice as “Don’t draw a boundary around the boundless” takes on additional meaning through the visual paradox. Tsai also creates a visual rhythm with Zhuangzi often speaking the final, moral-like statement in the white space of an unframed final panel.

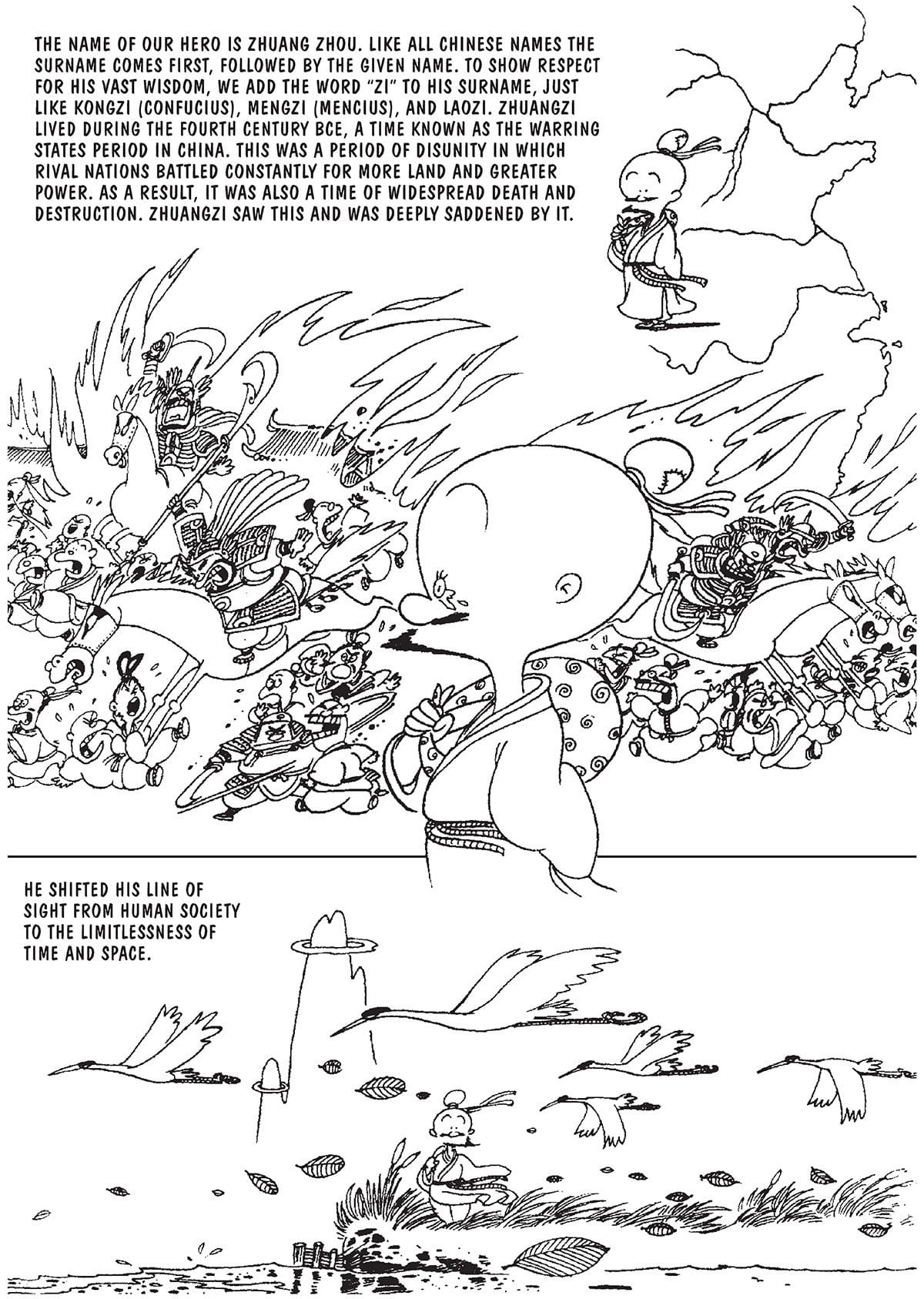

The most pleasantly peculiar elements are the cartoons themselves. Though The Way of Nature may be most English-speaking readers’ first encounter with Tsai, his style should seem familiar. While likely uninfluenced by him, Tsai’s carefully curving and angled shapes are reminiscent of Al Hirschfeld’s hyper-stylized caricature style popular in the US in the 1970s. (I first encountered Hirschfeld from his cover for Aerosmith’s 1977 album Draw the Line.) Tsai sharp clean lines form similarly exaggerated and simplified figures. No crosshatching suggests depth or texture, so the interior spaces of most bodies are as empty as the interior panel space surrounding them.

The most repeated figure, Zhuangzi himself, features a head roughly a third the size of his body. The top of his mostly bald head is impossibly large and round, his chin is a pointed triangle, his eyes are two tiny dots, and the “C” of his left ear is mirrored by the “C” of his right ear as well as the 45-degree-angled “C” of his nose.

While it’s odd to read the talk-balloon musings of a Yoda-proportioned philosopher, the juxtaposition provides an unexpectedly humorous undercurrent to the otherwise drily voiced philosophy. Would Zhuangzi approve of his language being mouthed by a cartoon parody of himself? I have no idea. But I approve. Still, Little Zhuangzi (he’s not named that, but there should be some way to differentiate the actual philosopher from Tsai’s rendering) alters Zhuangzi’s words just by appearing to utter them.

(Courtesy of Princeton University Press)

The effect is beneficial, especially when the themes are so familiar. That the advice to “genuinely appreciate every moment of life” and “just let it happen naturally” are clichés is a testament to Zhuangzi’s influence. By expressing them through cartoons, Tsai reduces the clichéd effect by giving the eye images to wander over, and the familiarity is softened by the gentle irony of the absurdly drawn speaker. Instead of sounding pompous or predictable, Little Zhuangzi seems playful and joyous—an attitude attuned to the actual Zhuangzi’s apparent intent.

Tsai also adds other touches. When the philosopher muses on the relativity of old age, one of his students comments on the 800-year-old-man drawn in front of him: “Wow, he is old!” A second chimes in: “You can say that again.” I’m guessing that dialogue doesn’t originate from the Chinese text next to it. Little Zhuangzi later admonishes another student for calling his teachings useless, telling him that “you’re really only using this little piece of ground you’re standing on, right? But, if we cut away all the rest of the ground around it … how useful is it?” In classic Wile E. Coyote fashion, the student hovers in mid-air for a frozen moment, before plummeting in the next panel and eventually landing in a pile of the repeated word “useless” holding up the much larger word “useful” which Little Zhuangzi stands on.

Would the over 2,000-year-old Zhuangzi approve of these flourishes? I hope so. According to Edward Slingerland’s forward, Zhuangzi (who may have been male, female, or several people combined) enjoyed innovation, adding new, often onomatopoetic words to classical Chinese. Translator Brian Bruya (who, according to Slingerland, is a master of biahua or colloquial Chinese) also provides a detailed introduction, substituting missing biographical information with the historical context (the Zhou dynasty was in disarray) and an overview of Daoism generally (Confucius was first) and Zhuangzi’s particular take (reject fate, ignore conventions, practice non-action).

It’s good advice, whether voiced by an ancient philosopher or his cartoon avatar.

(Courtesy of Princeton University Press)