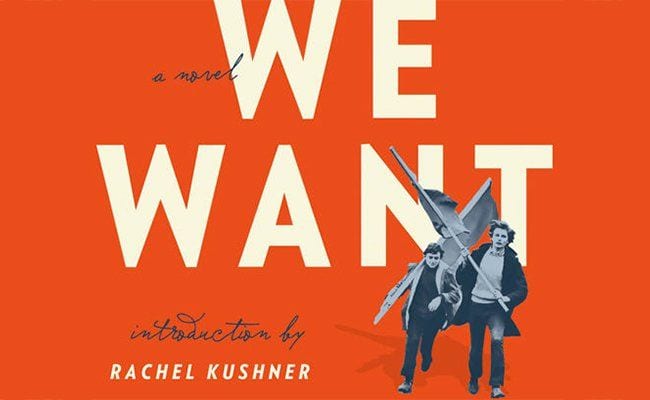

If there is such a thing as a ‘revolutionary novel,’ Nanni Balestrini’s We Want Everything is as good an example as any. The novel, first published in Italy in 1971, recounts in dramatic narrative form actual events that occurred in late 1969 in Italy: a massive mobilization and strike against Italian auto-maker Fiat that erupted into civil violence and came close to political revolution.

Balestrini — a poet, visual artist and writer — was himself personally involved in these struggles. In 1979, explains Rachel Kushner in an introductory essay, he had to flee the country on skis through the Alps in order to avoid arrest on charges of insurrection and terrorism, later dropped. But more than offering a dramatic recount of the events of 1969, the book offers a potent political analysis of today’s ‘mass worker’ and the struggles they face, couched in everyday language and dramatic action.

The novel offers a fast-paced first-person narrative. The language is blunt, unadorned and honest; the action sticks to key points and races along without detours from the main theme. The narrator comes from southern Italy, and like others from the region, he is lured north by the promise of easy quick cash in the newly modernising factory towns.

The context of this historical moment of capitalist development in Italy is important. For centuries Italians, particularly in the south, had lived an essentially feudal subsistence lifestyle. They eked out a living working the fields and farms of petty landlords, meeting their needs with relative ease but living in a constant state of abject poverty. They could gather food from the forests and fields around them; they could live in fairly basic housing and even sleep comfortably outdoors for much of the year. They wore simple clothing, handed down and patched up.

But then the factories arrived, luring young people off the land with the promise of cash and all that it offered: things their families had never even dreamed of. Stylish clothes, cars, modern homes of their own. At first the lure seemed attractive. But once they left their traditional lifestyles, they discovered they had new needs as well that they had never had before: the need to pay for housing, for food, for clothes for their families. To meet these needs, they had to work, and work hard; they no longer had the right to take a day off whenever they wanted to sit at the beach. To obtain the consumer goods they wanted and needed, they had to surrender to the tyranny of bosses and to the tyranny of work itself.

But they didn’t go without a fight, and that fight is the subject of Balestrini’s classic novel.

Kushner makes an important point in her introduction: the struggle depicted in the novel is predominantly depicted as a masculinist struggle. Women have very little presence in the novel and are objectified when they are. This is an ironic oversight, as Kushner notes, because women more than anyone had call to demand everything. It’s an unfortunate oversight too, she observes, since “it’s accurate to say that feminism had the most lasting and successful impact among the demands made in the revolts of 1970s Italy.”

The narrator — based loosely on a real figure, Alfonso Natella, to whom the author dedicates his work — is a happy-go-lucky southerner who comes north looking for easy cash. He gets it, drifting through a series of jobs, filling his wallet and then quitting jobs just as quickly as he gets them in order to enjoy the cash he’s earned. Then he finds new jobs, and becomes quite adept at scamming employers, as well.

The point of his continuous lies and scams is this: work is not something to be respected. He wants to have a good time, a natural human inclination, and so wants money, but sees no reason to respect the principle of work. At first his hatred of work is primal and intuitive; he has no real political analysis, just knows he wants to enjoy life and is happy to take the quickest route to get there. He’s willing to work for money — and only as long and as hard as it takes to get some — but understands there is nothing intrinsically worthy or noble about work. His views crystallize after he obtains one of the coveted jobs at Fiat, the Italian automaker. There, he eagerly joins in with students, union organizers and other activists who are vying with each other to gain adherents among the Fiat workers.

So I started stirring things up at the gates. Comrades, today we must stop work. Because we’ve fucking had it up to here with work. You’ve seen how tough work is. You’ve seen how heavy it is. You’ve seen that it’s bad for you. They’d made you believe that Fiat was the promised land, California, that we’re saved.

I’ve done all kinds of work, bricklayer, dishwasher, loading and unloading. I’ve done it all, but the most disgusting is Fiat. When I came to Fiat I believed I’d be saved. This myth of Fiat, of work at Fiat. In reality it’s shit, like all work, in fact it’s worse. Every day here they speed up the line. A lot of work and not much money. Here, little by little, you die without noticing. Which means that it is work that is shit, all jobs are shit. There’s no work that is OK, it is work itself that is shit. Here, today, if we want to get ahead, we can’t get ahead by working more. Only by the struggle, not by working more, that’s the only way we can make things better. Kick back, today we’re having a holiday.

The Politicisation of Anti-work

Gradually he comes to develop a political analysis as well. It’s not just that work is bad and pointless: it’s hypocritical as well, with arbitrary determinations of whose work is valued over others, and who gets paid what.

But organizing the workers and inciting them to go on strike is challenging at first. One of the barriers is what the narrator refers to as workers’ ‘neurosis’.

What is this neurosis? Every Fiat worker has a gate number, a corridor number, a locker room number, a locker number, a workshop number, a line number, a number for the tasks they have to do, a number for the parts of the car they have to make. In other words, it’s all numbers, your day at Fiat is divided up, organised by this series of numbers that you see and by others that you don’t see. By a series of numbered and obligatory things. Being inside there means that as you enter the gate you have to go like this with a numbered ID card, then you have to take that numbered staircase turning to the right, then that numbered corridor. And so on.

In the cafeteria for example. The workers automatically choose a place to sit, and those remain their places for ever. It’s not as if the cafeteria is organised so that everyone has to sit in the same place all the time. But in fact you always end up sitting in the same place. It’s like, this is a scientific fact, it’s strange. I always ate in the same seat, at the same table, with the same people, without anyone ever having put us together. Well this signifies neurosis, according to me. I don’t know if you can say neurosis for this, if that is the exact word. But to be inside there you have to do this, because if you don’t you can’t stay.

The narrator’s point is clear: the regimentation and routinization of work tasks generates a tendency to accept the routinization of daily life — a hesitation to question or challenge norms; an inclination toward accepting the status quo, even when there is no rule saying they have to.

We Challenge Everything

Two aspects of the workers’ struggle are impressively articulated and conveyed in We Want Everything. The first is an abject hatred of work — a clear indictment of the pointlessness and myth of work. Work is not noble, work does not contribute to the self or society; it is oppression and exploitation, pure and simple.

“Workers don’t like work, workers are forced to work. I’m not here at Fiat because I like Fiat, because there isn’t a single fucking thing about Fiat that I like, I don’t like the cars that we make, I don’t like the foremen, I don’t like you. I’m here at Fiat because I need money.”

The narrator is careful to emphasize that it’s not just manual labour, it’s not just certain kinds of work that are useless and disgusting — it’s all work. The narrator knows from the beginning, with an instinctive honesty, that he doesn’t like work, but it’s only as the novel progresses that he understands the oppressive and exploitative nature of all work, realizes the political and social nature of the demand — “Less work!”

The other refreshing dimension of We Want Everything is the perceptive critique of unions. Yes, this is a workers’ struggle, but it’s not a union struggle. The unions are portrayed as the enemy of the working class. They’re exposed as serving a mediating role for the company bosses; it’s a critique that is still appropriate to level at many unions today. The unions, in their efforts to retain their control over the workers’ movement, to ensure that they control the workers and members, connive and conspire to undermine autonomous and spontaneous workers’ struggles. They fear loss of control as much as the company bosses do. The bosses want to control the factory, and the union leaders want to control the movement.

What both fear is a spontaneous, grassroots, autonomous and democratic movement self-organized by workers themselves. Example: when the struggle starts, there are various categories of workers, each of which earns different salaries. Because the workers are demanding more money, the union and bosses negotiate the creation of new categories, to provide more pay scales. The workers reject this: they want the elimination of all the different pay scales, so that all the workers earn the same amount, and that it’s an acceptable amount for all. The narrator’s lesson is this: the unions want tangible victories to wave in the air; but the workers want a powerful united movement capable of taking on the bosses.

The Outcome of the Struggle Has Yet to Be Written

“The unions try to start the struggles one at a time, one finishing and another starting, to avoid the struggle widening and to stop the workers organising themselves in the factories from expressing their will autonomously. But the working-class struggle won’t be controlled this way. Almost every day a new struggle starts, and it’s the workers who start it. This is a big test of the working class’s strength… If workers end up divided and disorganised after the struggle, this is a defeat, even if something has been gained. If workers come out of the struggle more united and organised, this is a victory, even if some demands remain unmet.”

The narrator does a superb job of chronicling the gradual evolution of the unions’ role in the struggle: at first encouraging strikes and actions, but as the workers start organizing autonomously and making their own — often more radical — decisions, the unions begin to panic and escalate their own efforts to suppress the autonomous workers’ struggle. Eventually, they even cooperate with the bosses in this effort, each of them terrified that a system which benefits them both might actually be overthrown.

“Unionists, PCI bureaucrats, fake Marxist-Leninists, cops and fascists all have one characteristic in common. They have a total fear of the workers’ struggle, of the workers’ ability to tell the bosses and the bosses’ servants to go to hell and to organise their struggle autonomously, in the factory and outside the factory. We made them a leaflet that finished like this: Someone once said that even whales have lice. The class struggle is a whale, and cops, Party and union bureaucrats, fascists and fake revolutionaries are its lice.”

The Assembly

The varied themes come together in a workers’ assembly that takes place toward the end of the novel. Workers denounce the fact that the union, instead of fighting for equal wages for everyone, has settled for an even more convoluted hierarchy of pay. Workers point out that even though the bosses have conceded a pay increase, the price of consumer goods and housing is rising accordingly. What good is a pay increase, then? Others demand a guaranteed wage for all, regardless of whether they’re employed or unemployed.

The unions warn them against radical demands, since they could upset the country’s economic system. But the workers counter that’s precisely what they want: the destruction of an economic system that perpetually exploits them. Union reforms only strengthen that system. “We say no to the reforms that the unions and the party want us to fight for. Because we understand that those reforms only improve the system that the bosses exploit us with. Why should we care about being exploited more, with a few more apartments, a few more medicines and a few more kids at school. All of this only advances the State…”

But communism is no solution either, observe other workers — the communists are just as obsessed as the capitalists with making people work hard for no reward. What the workers want is an end to work. “Comrades, I’m from Salerno, and I have done every kind of work in the south as well as the north and I have learned one thing. That a worker has only two choices: a grueling job when things are going well or unemployment and hunger when they go badly. I don’t know which of the two is worse.”

“We started this great struggle by demanding more money and less work. Now we know that this is a call that turns everything upside-down, that sends all the bosses’ projects, capital’s entire plan, up in smoke. And now we must move from the struggle for wages to the struggle for power. Comrades, let us refuse work. We want all the power, we want all the wealth.”

The Struggle Continues

The struggle against work portrayed in the novel was sparked by a particular type of worker. Earlier in the century, Italian workers’ struggles (like elsewhere) were defined by skilled workers who could more effectively demand more wealth because of their highly specialised skills. And it was that type of worker around which left-leaning political parties and labour unions organised their strategies. But in the ‘60s a new type of worker appeared: “adept at a thousand trades because he has no trade, without a single professional quality even when he possesses a diploma, lacking a steady job and often unemployed or forced into casual service, who can’t find work and so seeks it in Turin, in Milan, in Switzerland, in Germany, anywhere in Europe. Who finds the hardest, most exhausting, most inhuman jobs, those that no one else is prepared to do.” It is on this worker, Balestrini points out, that the postwar economies of the West were built.

What is significantly different about this worker is that unlike the skilled worker of the past, who could often take pride in their sought-after technical skills, the new worker is defined by “his ideological estrangement from work and from any professional ethic, the inability to present himself as the bearer of a trade and to identify himself in it. His single obsession is the search for a source of income to be able to consume and survive… For him work and development are understood solely as money, immediately transformable into goods to consume.”

As Balestrini notes in his afterword, this worker is in many ways still the worker of today. In the ‘60s and ‘70s the state and the capitalist system hastily responded to the workers’ challenge with a series of measures which suppressed that struggle for a time — automation and robotisation of factories, outsourcing of production to the third world, co-optation of unions and where none of these strategies worked, brutal police repression. But the workers, the issues, and the struggle continues today.

It was because of this new and unpredictable type of worker — who wasn’t fooled by the notion of a ‘work ethic’ and was uninterested in the elitist machinations of unions and political parties — that unprecedented revolts broke out across Italy (and elsewhere) during this period. The novel ends with a dramatic street battle between workers and police, the end of which is left hanging. Throughout that dramatically depicted battle, which rages throughout the city, it becomes clear that the workers’ strength comes from the self-empowered, self-organised movement they have been building in the weeks and months previous.

These weren’t workers following union instructions, or students playing at textbook revolutionary. These were workers who had challenged their bosses face-to-face in the factory; who had walked off the assembly lines in solidarity when one of their fellows was fired. It was their unity that was their strength — not their union or their political ideology. And as the battle rages, they realize that this unity can bring them real power.

“People kept coming from all around. You could hear a hollow noise, continuous, the drumbeat of stones rhythmically striking the electricity pylons. They made this sound, hollow, striking, continuous. The police couldn’t surround and search the whole area, full of building sites, workshops, public housing, fields. People kept attacking, the whole population was fighting. Groups reorganised themselves, attacked at one point, came back to attack somewhere else. But now the thing that moved them more than rage was joy. The joy of finally being strong. Of discovering that your needs, your struggle, were everyone’s needs, everyone’s struggle.”

The aftermath of the battle is left hanging, uncertain. Balestrini’s message is clear: the outcome of the struggle has yet to be written. “Capital only appeared to have won a victory; it has triggered a process that leads unavoidably to a confrontation with the underlying issue, expressed clearly 30 years ago in the struggles of the mass worker with the slogan ‘refusal of work’,” writes Balestrini in his afterword.

More and more the automation of production, and also the possibility in general of trusting almost every type of work and activity to machines and computers, requires a laughably small quantity of human labour power. Therefore why shouldn’t everyone profit from the wealth produced by machines and from the time freed from labour? Today, absurdly, work that is no longer necessary continues to be imposed because only through this is it possible to conceive of the distribution of money, allowing the continuation of the cycle of production and consumption and the accumulation of capital.

It’s surely no coincidence that Balestrini’s novel is undergoing a renewed popularity, at a time of mass mobilizations by a public whose ideological estrangement from work echoes so strongly with that of the characters in his 45-year old book. As demands arise again that echo the demands of the period — less work, more pay, more leisure, guaranteed income — We Want Everything sends a stirring reminder that these are not new demands, and that although it is a new generation rising to the challenge, it is the same fundamental struggle that continues.

“A new era is waiting for humanity, when it will be freed from the blackmail and the suffering of a forced labour that is already unnecessary and the enslavement to money, which prevent the free conduct of activity according to the aptitudes and desires of each and steal and degrade from the rhythm of life, at the same time that there is the real possibility of widespread and general wellbeing. This was the meaning, and could again be the meaning today and in the future, of that old rallying cry: Vogliamo tutto!” We want everything!