The musical comedy duo of Garfunkel and Oates (Ricki Lindhomme and Kate Micucci) illustrates a problem that’s plagued partners for years, in particular, Art Garfunkel, as he’s defined himself within and without the presence of childhood friend Paul Simon. The joke starts with their very name. Garfunkel and Oates are supposed to be seen as also-rans, incidentals, finally coming out from behind the shadows of their more popular (or talented?) partners. If Simon and Hall created a partnership, they’d cancel each other out. After all, leaders can’t share a stage. Excessive ego from the wizards at the control booth and the freedom for self-indulgent flourishes needs a Type A and a Type B.

The other joke about Garfunkel and Oates is that their counterparts weren’t known for grandstanding rock star behavior. If the bottom half of a folk duo and a blue-eyed soul partnership come together, perhaps the only result can be comic.

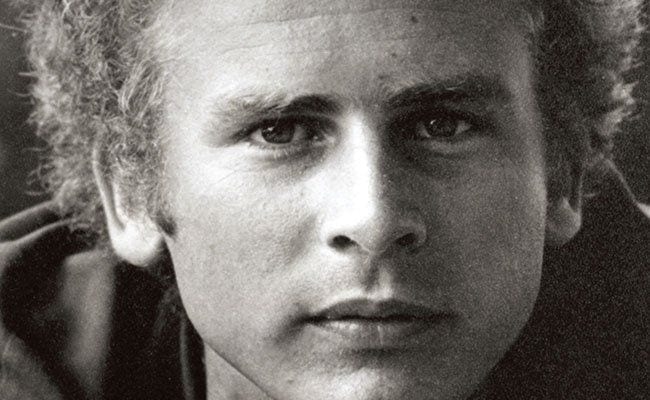

In his new memoir, What Is It All but Luminous: Notes from an Underground Man, the 75-year-old Garfunkel reveals the soft, lush, probably difficult, and definitely peculiar character that has been taking notes, observing, singing, and remembering for over 50 years. He’s walked across the United States and through many other parts of the world. He’s starred in such landmark films as Carnal Knowledge and oddities like Bad Influence. The Garfunkel known for the soaring showcase songs as “For Emily, Wherever I May Find Her”, “April Come She Will”, and “Bridge Over Troubled Water” was deeper, needier on film, with a touch of East Coast upper-class intelligentsia entitlement and poor impulse control.

Garfunkel definitely understands how to open a memoir. It’s 2 January 1969, and he’s packing for a trip from New York City down to Mexico to appear in the Mike Nichols adaptation of Catch-22. It’s a scene close to the heart of any Simon & Garfunkel fan who remembers the opening of “Only Living Boy In New York”. In that song, Simon sings to his partner: “Tom, get your plane ride on time/ I know that your part will go fine”. They were known as teen rock duo Tom and Jerry in the late ’50s, scoring a minor hit with “Hey Schoolgirl”. As with much that came in the lives of Art Garfunkel and his pal Paul Simon, though, two Queens friends born within weeks of each other in the fall of 1941, the intensity of a childhood friendship bonded forever through the love of music could break at a moment’s notice:

“Then, in 1958 comes Betrayal… Oh so dramatic… It is a surprise blow to the gut. Boy’s love is a beautiful thing. I loved my turned-on friend… Surprise…

He was releasing a record behind my back… He’s base, I concluded… the friendship was shattered for life… I never forget and I never really forgive — just collect the data and speckle the picture.”

It’s a suitably dramatic moment near the start of this book, and the reader wonders if there will be deeper eviscerations of his one-time close partner. Wisely, Garfunkel takes the high road, and it’s the only logical approach. Still, Garfunkel knows he both cannot and should not erase Simon from the story. Simon was and remains a big presence in the life of Garfunkel, but he is only one of many elements to the years covered here. For Garfunkel, theirs was “…a singular love affair… From age eleven to today, a span of sixty-four years, Art and Paul have been at work to entertain, win the respect of, and dazzle one another.”

There are certain indulgences the reader will need to accept as a given in What Is It All but Luminous. That Garfunkel will occasionally refer to himself in the third person can be forgiven because the way he unravels his story, he has to deal with the persona of the artist. Who was he as part of Simon & Garfunkel? He’s telling us that the connection has been strong for 64 years, and there’s no reason not to believe him. The difficulty seems to be in the fact that chronologically, the recording career and sporadic reunions (1963-1970, 1981, 2003, 2009), reflect a partnership that thrived in the ’60s and (perhaps understandably) has coasted on the fumes of legacy and audience goodwill since 1970. Are we truly meaningful artists if we stop looking for ways to interpret the same old song?

Garfunkel may be humble and graceful, appreciative of opportunities and aware of his place in the star-making machinery, but he isn’t beyond boasting. “Paul won the writer’s royalties, I got the girls,” he writes. Later, in a conversation with John Lennon about his Paul, Garfunkel suggests: “return to the harmony. If you loved making the sound with him, forget personality, forget all history. Go for the jelly roll.” Much of this memoir leads us to believe Garfunkel didn’t take his own advice to heart, but that doesn’t matter. The struggle for ownership of the songs they performed together must have been overwhelming for Garfunkel. It’s not about who intellectually wrote the material but rather who brought it to life:

“Authorship may be trumpeted. It may be declared. It may be declined… Your beautiful musical soul is the author of mine.”

The ’70s were a halcyon time for Garfunkel, or at least the first half of the decade was. Simon & Garfunkel had split, but Garfunkel found roles in the two aforementioned Mike Nichols films Catch-22 and Carnal Knowledge. He recorded strong albums, Angel Clare and Breakaway (the latter featuring his 1975 reunion hit with Simon “My Little Town”). 1977’s Watermark featured the sublime three-part harmony of Simon, Garfunkel, and James Taylor singing “(What a) Wonderful World”. Garfunkel embraced Jimmy Webb songs, Randy Newman ballads, American standards, and made them all his own in a way that was perfect for the easy listening FM era. Garfunkel saw an opening in the pop star field and he took it.

Early in the book, Garfunkel reflects that his life has been a two-act play. The first ended with “Bridge Over Troubled Water”, what he called the summit, and the reader wonders what that means not just for the remainder of his life but the rest of the book. He lost his girlfriend Laurie Bird by the end of the ’70s, and things seemed to understandably spiral down into darkness. He had 1981’s “Concert in Central Park” with Simon, and he started to walk and write. “Since Laurie died, I lived in my own rarefied air. I put the ‘e’ in artist every day.” He connects with his pal Jack Nicholson, who tells him “G, I’m your new partner. I talk, you write it down. You can take all the credit and money this time.”

Garfunkel’s heart breaks and seems to be still breaking in the middle passages of this book. Far from a conventional memoir, What Is It All but Luminous is a collection of journal entries, poems, and reflections about life around him, and if things started to drift by the mid-’80s, perhaps it’s understandable. Garfunkel’s walking journeys and motorcycle sojourns are well-chronicled elsewhere, and when he gets to them in this book the reader is understandably frustrated. Do we want to go on this trip with him? How will this long journey be compressed into a compelling narrative?

The short answers are yes, and it’s hard to tell. We want to go on this trip because we know the angelic voice from Simon & Garfunkel, the tall one with the curly red/blonde afro who always stood beside his partner, never behind. The long road trips and other solo odysseys are part of the bargain, and it’s here where much of What Is It All but Luminous gets filled with lists and information. There are four lists of books that he’s read during certain times, a list of the people to whom he is devoted, an alphabetized list (a-n) of what he believes our years beyond 65 are all about, a list of life achievements, what’s on his iPod, a collection of affirmations, and the 25 records that changed his life. It’s exhausting and elaborated on in more detail in ArtGarunkel.com, which is where a more focused writer might have kept these items. Parts boastful (the books), and sincerely impressive (life achievements), the lists reflect the life of a math major, a man eager to be accountable for things, to collect experiences and watch them as they interact with each other. Compiled in this matter in a book that’s easily absorbed over a few hours, they seem more like stalling tactics than passages that will truly add different shades of understanding to the rich and varied life of this man.

What Is It All but Luminous can be a frustrating read, yet it’s admirably consistent. It’s the story of a man loyal to his friends, equally comfortable hanging out with the inimitable Nicholson and then spending days at a time alone, in solitude, on a literal and figurative journey. The reader might have been better served with more reflections about time on the set of Carnal Knowledge and Catch 22, but Garfunkel offers equally important reminiscences about the Everly Brothers:

“…it all took flight when Don and Phil Everly started having hits in 1956… Every syllable of every word of every line had a shine, a great Kentucky inflection, charisma in the diction. From moment to moment they worked the mic with star quality. The Everlys were our models.” He almost ruins this goodwill much later in the book when- again reflecting on the ’50s, he temporarily assumes a dialect:

“How to remember de rock and roll of de early days… In dos days we just had Elvis an’ de Fab Four.”

It’s strange, borderline offensive, but by this point, the reader is accustomed to Garfunkel’s perspective. The greatest love for Art Garfunkel has obviously been his wife Kim, married since 1988, with whom he’s shared his life and the raising of two sons. However, the deepest love story still seems to be the one between Art Garfunkel and his childhood friend Paul Simon. In a somewhat discursive note late in the book, Garfunkel notes something that can stand as a major theme in this strange but endearing and compelling book. It’s about companionship, about agape love or romantic connection, and about a life that can only be truly fulfilled when shared with another person:

“When do-si-dos are over, show the hidden heart — honor your partner.”