There has always been something inviting and tempting about the dependability of a raging visionary madman prophet, roaming the streets of the city, spouting scripture from an unknown source. Are they the originators? Are they the neglected and marginalized, relegated to their own space in a local mental health rehabilitation center? We think of the furiously tight scribbles on parchment or the densely populated landscapes of their primitive art, the product of these madmen (and women), and we take it as our own. This is art, we claim. This is truth. How we have viewed these marginalized prophets of Biblical doom through our modern eyes can be seen in the implications of horror in tattoo art in Thomas Harris’s Hannibal Lecter series, the doomed inevitability in any number of rapturous apocalyptic visions, and the overall message that a Final Judgement is coming. Find humility, or at least be prepared to face your just rewards.

The works of William Blake gradually but conclusively made its way into the poetry of Allen Ginsberg, the principles of Jim Morrison and The Doors, incantations from Van Morrison, and the religious work of Bob Dylan. Indeed, Blake has been everywhere and nowhere at the same time, perhaps just as he would have wanted it to be.

William Blake and the Age of Aquarius — a beautiful volume published in conjunction with Northwestern University’s Block Museum of Art exhibition of the same name (23 September 2017 — 11 March 2018) — wonderfully, strikingly, fantastically puts this formidable artist/ poet/ visionary into a logical context. The grotesque horror film imagery of Thomas Harris’s Hannibal Lecter series isn’t here, nor is anything else so definitively doomed. Instead, William Blake and the Age of Aquarius definitively places its subject with Norman Mailer and others. It’s 21 October 1967, and Stephen F. Eisenman clearly wants us to see the relevancy of Blake, who at that date had been dead 150 years. Eisenman places some Blake lines (from Marriage of Heaven and Hell) into the mind of fellow protester Tuli Kupferberg (from the Fugs.) Here’s the line, followed by Eisenman’s reflections: “‘Sooner murder an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires.'”

“How serious was Blake? [Blake.] The lyric could be used to justify both state terror and the violence of a revolution that goes out of control. In fact, it predicted the mayhem that concluded the 1960’s…”

Is Eisenman on target here? Perhaps. That seems to be the key Eisenman and his fellow contributors want us to take away from this text. What we understand about Blake, born in 1757 and given the Biblically prescribed life of three score and ten, is that his “…subject matter is as dichotomous as his identity and artistic style… The Bible, Dante, Shakespeare, Milton… his own imagination and visions.” It’s that last element, visions, that Eisenman wants us to clearly understand (if not accept.) In his lifetime Blake claimed to have seen visions of angels, demons, gods, dead kings, and poets from the age of four until the end of his life. He wrote books of illuminations, filtered his condition into his art, and Eisenman reminds us that in the time of William Blake “…seeing phantasms was not so uncommon.” How those who received visions filtered them through their art, we can conclude, is what separated the artists from the unfiltered madmen.

Later in Eisenman’s essay (accompanied as the entire book is by over 100 illustrations) we learn that the American revival of the British William Blake started with Walt Whitman in the mid-19th century, and went through Allen Ginsberg in the mid-20th. This is a well-trod path by those who followed The Beats (the literary style and the literal beat of a different drummer) but Eisenman makes it fresh. Here is Ginsberg, in 1948, suddenly hearing Blake himself read from Songs of Innocence and Experience:

“All at once, Ginsberg later said, he apprehended the unity of things material and spiritual, religious and carnal. Looking out the window, he saw ‘into the depths of the universe’ and understood that ‘this was the moment that I was born for.'”

If Ginsberg is the best entryway into understanding Blake’s influence on the Age of Aquarius, and the argument is easy to make, then the latter’s 1955 classic Howl is the key to open that door. Ginsberg saw in Blake, particularly the latter’s poem The Sick Rose, “…that simple lyrics have great authority when employed to construct dreamlike or nightmarish images…” The idea here is not simplicity in implied power so much as just the measures, one syllable, sometimes more, but always direct and immediate. In Blake, Ginsberg saw the power of an apparent child-like vision to bring home the strongest ideas.

Eisenman brings in Blake’s doors of perception, from the latter’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and the reader recalls the Doors. No matter what one might think of Jim Morrison The Lizard King, that self-declared American Poet, the connections to Blake are clear and understandable. Reading lines from Blake like “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite” makes the reader think (logically) that the man might have wished to “break on through to the other side” as Morrison intoned in 1967. No matter the Sex God posings of Jim Morrison (perhaps more Val Kilmer and Oliver Stone’s fault than Morrison’s), the strength of the Doors’ lyrics still owe their connection to Blake’s sensibilities.

With Aldous Huxley and his 1954 text The Doors of Perception, equally influential on Morrison, the reader gets a deeper connection between Blake and the Age of Aquarius. It’s not always a direct link, however. There were several loops to enter, but they always went back to Blake as the source material. Eisenman notes that Huxley’s text, and others from Ginsberg, Timothy Leary, William S. Burroughs, and Ken Kesey, sparked interest in outside stimulants, particularly LSD. However, as Eisenman notes, Blake “needed no chemical stimulants to experience visions and publish prophesies. But he was in agreement with his mid-twentieth century followers that knowledge of the infinite can only be achieved by a rejection of law and reason…” This seems to be the key to understanding Blake. It was about sensual enjoyment, about searching for something deep. The idea seemed to be that by “…expunging the notion that man has a ‘body distinct from the soul’ the true artist reached communion with something extraordinary.

Eisenman’s examination of Blake in the section “Blake’s Influence on Hendrix and Dylan” offers some interesting takes on what may not have been well known. Eisenman draws connections between Jimi Hendrix’s “The Wind Cries Mary” and Blake’s poem “Mary”, where the “arrows of desire” crossed the centuries without losing any power. We learn that Hendrix was a big science fiction fan, and that Blake was considered a progenitor of the form. As for Bob Dylan, the influence seems stronger and more potent if only because Dylan is an artist who never faded away. He might not be playing “A Hard Rain’s a-gonna Fall”, “Visions of Johanna”, and “Every Grain of Sand” each night on his so-called “Never-ending tour”, but the influence remains. Eisenman draws particular attention to “A Hard Rain’s a-gonna Fall”, which is less obvious though no less potent in its Blakean influence:

“…’A Hard Rain’ has verses that, in their reference to young boys and girls (‘my blue-eyed son… my darling young one’) and childhood danger and loss (‘a newborn baby with wild wolves all around it’), invoke the world of Blake’s ‘Little Boy Lost’ and ‘Little Girl Lost’ poems.”

While Dylan lyrics like the entirety of 1981’s “Every Grain of Sand” might be more direct, complete adaptations of Blake, the influence is everywhere. As Eisenman continues in his essay, which encompasses almost a third of this text, he covers the Blake influences in the art of Kenneth Patchen, and the “Auguries of Influence” direct Blake homage (by photographer Diane Arbus) in the December 1963 issue of Harper’s Bazaar. As his essay ends, Eisenman emphasizes the importance of understanding the true meaning of innocence as used by Blake:

“They meant by it the mental and physical pleasures that come from creative work and sexual love…toppling the abstraction of law that denies people the full exercise of freedom…”

How this cry for true freedom and liberation through the “truths” that artists from the Age of Aquarius is espoused truly proves a mixed blessing. The strongest work from any of the wild-eyed artistic prophets of the post-WWII generation only benefits with age. To accept the post-Epicurean seekers of pleasure who raged against the darkness of everything requires a clear understanding of Blake not just as an artist but also a presence that refuses to fade away.

In Mark Crosby’s chapter “Prophets, Madmen, and Millenarians”, the danger gets deeper. Blake had long been seen as a counter-culture festival, ages before the Age of Aquarius. As Crosby sees it, “…part of Blake’s appeal to modern audiences is the complexity and diversity of his creative output…how his work not only critiques systems of power…but also emphasizes the power of the imagination…” There is the power of John Milton’s Paradise Lost still being interpreted and confronted in our time. Blake’s mother Catherine Armitage was a member of a Protestant congregation led by a theologian and mystic (Nikolas von Zinzendorf) whose Kabbalistic theories “…stressed the spiritual importance of male and female sexuality.”

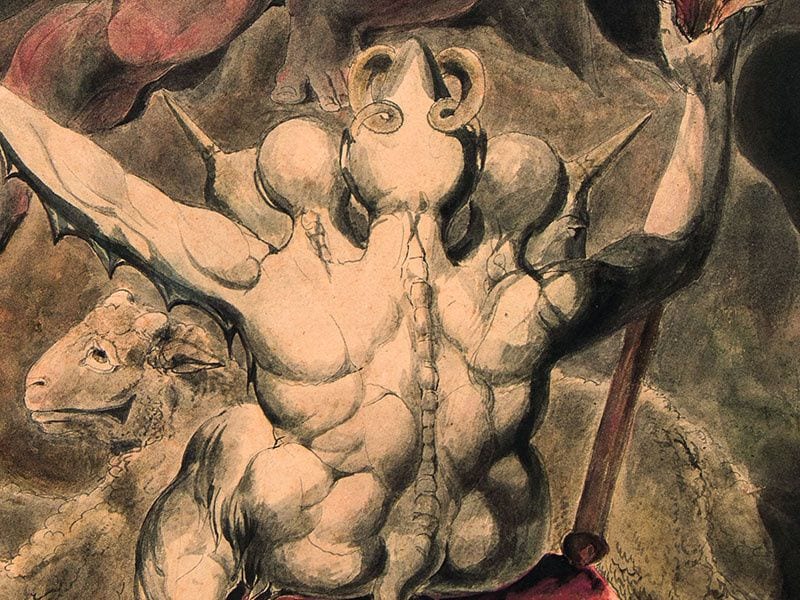

Crosby emphasizes here how Blake viewed the importance and perhaps the sacred state of childhood. In Songs of Innocence and Experience, there were critiques of organized religion (“The Garden of Love”) systematic child abuse (“The Chimney Sweeper”), and “…the institutionalized culture of benevolence that perpetuated poverty in “Holy Thursday”. From the grace of childhood, Blake travels the spectrum into the other side, the horror of such art as Blake’s The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun. It’s a scene from Revelations 12:1-4, and the terror is overwhelming. There are more beasts, six-headed monsters wielding terrible swift swords, and the reader might get overwhelmed by how powerful these images remain.

In Elizabeth Ferrell’s “William Blake on the West Coast”, we explore the Beats of the ’50s, those finger-snapping precursors to the hippies. Ferrell examines how the alternative communities prevalent there picked through elements of Blake’s oeuvre to suit their purposes. Poet Michael McClure claimed: “We’ve grown up together. Blake and I grew up together.” For McClure, there was the attraction of Blake’s antidualism.

“Blake’s belief in the unity of body and soul led him to advocate free love on the grounds that sexual pleasure is a simultaneous physical and spiritual liberation…”

There are images from the work of artist Jay Defeo that Ferrell argues go deep into the mission of uniting reason and imagination, the material and the spiritual. Such pieces as The Rose (1958-1966) are infinite in their perspective. Look deep into the center of the circle and hope for a safe return back to your starting point. For Defeo, much like one might imagine Blake feeling, the work was “…an example of what I feel intuitively and what I know cerebrally meshing together without any separation.” Wallace Berman’s 1958 works Portrait of Jay Defeo feature front and back images of the artist, nude, exposed in a pose that’s an homage to Blake’s 1795 work The Dance of Albion. The circle never breaks. This chapter takes a deeper dive than might be comfortable for the casual reader, so be forewarned. Staying with it will reap great rewards. There are collages, cutting and pasting and appropriations. Artist Helen Adam’s 1958 piece “I Had Sweet Company Because I Sought Out None” features a blonde woman in an orange glow having her chin nuzzled by a caterpillar and preparing for a kiss from a lizard.

In Henry Leveton’s “William Blake and Art Against Surveillance” we once again go deeper into the stranger corners of the artists’s mindset. He liked to visualize a presence he called Urizen, his “…mythic personification of rationality, the clockwork universe, and deism, the belief that God created the world but then left it to run by itself…” Leveton effectively and compellingly ties in the connection between the apparent subversive nature of Blake’s work in his time and the fact that by the mid-20th century, “…the idea of surveillance was politically and artistically prevalent in American art… Before the end of the 1940s artists associated with abstract expressionism would have been aware that their work had come into view of government watchdogs.”

We may be familiar with the name and reputation of Jackson Pollock (whose 1950 piece Autumn Rhythm is reproduced here), but Clyfford Still proves to be a stronger revelation. His 1945 Untitled (Fear) and 1946 PH-69 are dark patches and slashes of color and paint. Sam Francis’s 1960 Damn Braces also works from Blake’s experiments with color. As Leveton notes, “Blake crafted a means of color printing that captured a profound disorder the artist-poet believed to be paradoxically fostered by Urizenic order and control.”

Similar ideas are explored in a deeper level through John P. Murphy’s chapter “Building Golgoonza in the Age of Aquarius”. This covered a strange segment of American history during that time which featured a couple in Athens, Ohio who (from 1969-1986) built their own version of the title community. Whatever this commune represented seemed to be rooted in Blake’s ideas that the eternal nature of all creative and imaginative acts were to build themselves up as a city unto God. Whatever falls apart after the ethereal structure provided by art will then be inhabited by humanity. Murphy also cites Colorado’s Drop City (immortalized in the TC Boyle novel of the same name), and The Woodstock Festival, the ultimate expression of community in the Age of Aquarius. The Golgoonza commune became a church of Blake and eventually burned down in the early 21st century.

Mark Crosby’s chapter “Sendak, Blake, and the Image of Childhood” beautifully captures how the great artist Maurice Sendak drew inspiration from Blake. Crosby tracks what he sees as Sendak’s “…journey from iconoclast to mainstay of popular culture…” and how it seemed to parallel the recuperation (or resurrection?) of Blake in the Age of Aquarius. Sendak had apparently spent his life immersing himself entirely in Blake. He illustrated select poems from Blake’s Songs of Innocence. In his illustrations for Ruth Krauss’s Charlotte and the White Horse, Sendak noted this was his “first attempt to unite poetry with William Blake.” There are no explicit quotes or appropriations so much as an adherence to composition of characters and colors. Sendak’s own My Brother’s Book (2012), his final publication, draws from Blake’s work about and inspired by Milton. It’s the end of life, the fall of man, but there’s no tragedy here. As Crosby notes, “…Sendak sought to prompt readers of all ages into a Blakean view of childhood…we should all be able to return to the bedrooms of our youth and the assurance of a hot supper.”

In “Blake Now and Then” W.J.T. Mitchell notes that the purpose of William Blake and the Age of Aquarius, published to coincide with the exhibit of the same name, the idea of “Now” is 2017 and “Then” is 1967. For Mitchell, though, it has to be deeper, and he takes a more Blakean view of “Now and Then.” It’s about “…the relation of any experiential moment of human time to the entire span of human history envisioned, recorded, and transmitted from age to age in the arts.” Blake’s is a tough and at times overwhelming legacy to consider. Who was he in his time? Who was he in the Age of Aquarius? In William Blake and the Age of Aquarius, those familiar with William Blake’s work will welcome the considerations of his legacy as seen through visual and auditory art since the mid-20th century through today. Those unfamiliar with Blake should still be fascinated by how the man’s work has drifted through the ages without losing much of its power. No reader of this book will come away from it unmoved and indifferent to the potential of the artistic sensibility as it comes to terms with light, dark, and everything in between.