In 2014. British musician and producer, East India Youth, released, for many people, one of the albums of the decade. Total Strife Forever was a striking, idiosyncratic electronic album that fused everything from techno to orchestral pop and brought with it a Mercury Music Prize nomination and widespread critical praise. Quickly following it up with the more eclectic pop of Culture of Volume, the man behind the music, William Doyle, took another bold step in what promised to be a fascinating and varied career. And then nothing.

For those that fell in love with those albums, the apparent disappearance of the man behind the music was something of a mystery. The truth is, sadly, all too common for an artist who achieves sudden and unexpected success. For Doyle, success became an exhausting slog of touring and press. With little guidance as to how to navigate a career in music, his fears and anxieties were amplified until the internal clamor became too much. Wisely, Doyle extricated himself from the East India Youth project and retreated from public view.

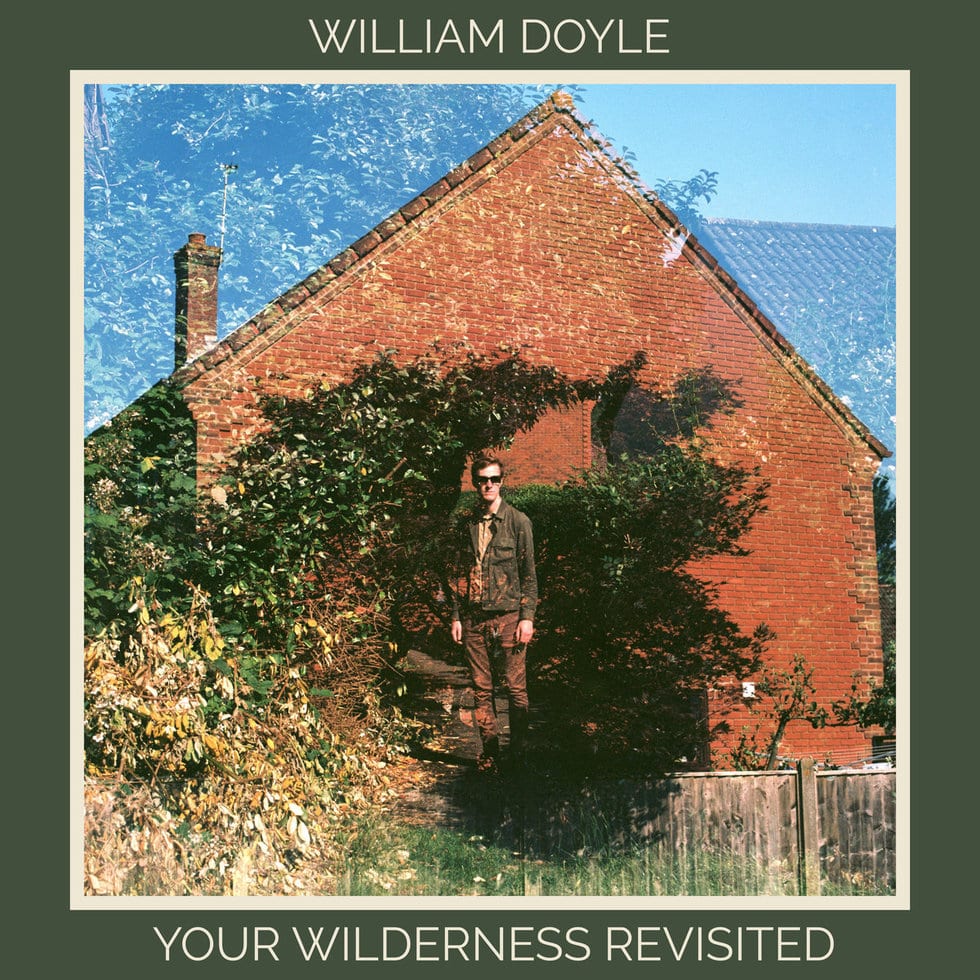

Taking solace in a pair of excellent ambient releases, (The Dream Derealised and Lightnesses I and II), he has spent time recovering and focusing on what’s important. Now, he is back with his first release under his name, the dazzling Your Wilderness Revisited.

Inspired by his teenage years, living in the relatively quiet town of Chandlers Ford just outside Southampton, the album is a triumphant celebration of suburban living. Naturally, it’s a very personal album with Doyle freshly examining the effect suburbia had on his formative years while also attempting to rehabilitate the people’s perception of it. Musically, the album blends articulate layers of instrumentation to produce a richly satisfying blend of baroque pop, avant-garde jazz, and electronic indie. Doyle spoke to PopMatters to tell us more about the end of East India Youth, his experience of living in the suburbs, and how the album came into being.

What was the first album you fell head over heels in love with?

My honest answer is Hybrid Theory by Linkin Park.

When did you know you wanted to pursue making music as a career?

I thought being in a band would be a cool idea after I started getting into them. It wasn’t until I was 16 or so, after doing it for a while, that I thought maybe this is what I want to be doing for the rest of my life.

Was it easy for you to let people hear your first compositions?

Absolutely not. It took me until I was about 22 to be comfortable showing people works in progress. An unfortunate perfectionist streak runs through me. I’d put stuff up on MySpace when I was a teenager, but not until after it had been labored over for some time.

How quickly did those ideas start to become that identifiable East India Youth sound?

Well, those pieces were things I was working on alongside another band I was in. I’d been writing and recording music for about eight years by that point. Over the space of a year or two, towards the end of that band, I’d started to amass a lot of electronic music that I’d made, and it struck me that it was actually quite good and maybe worth pursuing.

Are you far away enough away from your work as East India Youth to appreciate all you achieved?

It’s a good question. I don’t think so, no. I’m immensely proud of that first album, and I’m happy that people seemed to really resonate with it. But I think it will take me a while before I can look back at that time with the fondness it deserves.

What do you think you learned from your more ambient albums (The Dream Derealised and Lightnesses I and II)?

That making ambient music is a wonderful discipline that can make you listen closer and for longer.

Why is now the right time to release music under your own name?

It always was the right time. But this record feels inextricable from myself.

Who is William Doyle and how does he differ from East India Youth?

He doesn’t wear a suit, day-in, day-out. I’d become so absorbed by that character as an extension of myself, that I couldn’t even go down to the shops to get some milk without putting a tie on. I’d also not really bought many other clothes for a few years.

I think I’d started to become someone I wasn’t so happy with. Self-obsessed, there, but never really present. Being comfortable putting things out under my own name required me to know myself again, not just the self that sells records. It also required me to be more compassionate, loving, and inclusive with the people around me. I’m still working on those things, but I feel a lot better in myself now.

The album is very much a celebration of suburban living, how did your experience of living in the suburbs shape you?

I moved there when I was 13 after my dad had died. So at first, it was a strange experience that didn’t seem to make sense. I suppose because there wasn’t much to do as a teenager in the area, you had to use what was given to you. If that wasn’t getting drunk or high in parks and woods, then it was getting drunk and high on listening to music in parks and woods, and walking and cycling around thinking about the world and your place in it, creating your own fiction and mythologies. It was an amazing place for the imagination.

Do you think there is a generally negative idea of what suburban living is?

There is. It’s not hard to see why. In Britain, at least, they can be very monocultural places. They don’t really value the arts in the same way that the bigger metropolitan centers in the country do. Everyone becomes very comfortable and protective of their own domain. I think I had a good experience because we were on the outskirts, never far away from a field or woodland. My view is rose-tinted, of course, as I was a teenager without the same responsibility I have now. But I also think that if we invested more time and love into these spaces, they would bloom.

How has your view of the suburbs changed after living in places like York and London?

Sometimes I want to go back, but I know that I’d miss the excitement and temptation of cities. York felt like almost like a halfway home, but it was just a bit too far away from everyone I knew.

Photo: Matt Colquhoun / Courtesy of Practice Music

Some of these songs you’ve had for years, which were the oldest and what changes have there been to them over the years?

The whole thing took about four years to make, and all of the songs apart from one had their genesis around the same time, in mid-2015. So they’ve all changed drastically during that time.

Can you describe the typical journey of a song from the idea in your head to the finished product?

My process is usually very slow refinement and editing over a long period of time. With this album, each song started with one sound that then suggested another sound, or a vocal melody, or suggested a feeling or atmosphere, and it was my job to follow those suggestions and see where they took me.

Can you always find the sound that’s in your head? How easy is that?

Not always, but it’s the mistakes you make trying to get there that produce the really great results.

Did you ever find yourself going too far down the rabbit hole in terms of trying to find the right sound or getting down exactly what you wanted?

Oh my god. So many rabbit holes. So many rabbit holes with absolutely fucking nothing in them. That’s the joy!

Where there any tracks that were total pains in the ass?

“Blue Remembered” and “Continuum” did not want to work. “Blue Remembered” is one of the only tracks on the album that I did completely, entirely, by myself, which is probably why it was difficult. “Continuum” was rescued with help from my dear friend George Hider. Heaven is other people.

Musically, what were the touchstones for you when making the album?

Yikes. I tried not to have any, really. I think the artists who are in my DNA probably came out there somewhere. Perhaps more thematically or atmospherically than wholly musically, these were some kind of touchstones: These New Puritans – Field of Reeds; Perc – Wicker & Steel; Julia Holter – Loud City Song; Darren Hayman – Pram Town; Owen Pallett – In Conflict.

What are the main ways in which you think have progressed on this record? Writing, understanding, composition, structure.

I think I worked really hard to make every song a mini-epic in itself, which is something I’ve not done before. I think every song has a very identifiable atmosphere or mood.

What do you think you learned about yourself in the course of making this album?

That I probably need to give therapy a try.

Do you think you have fully realised your vision of what this collection of songs should be?

I love it dearly, but no. I don’t think any artist ever does, and that’s what compels them to keep making.

Collaborating with people like Brian Eno and Laura Misch on this record, who would your dream collaborator be?

I would like to make a record at Tiny Telephone with John Vanderslice one day.

What would be your three desert island records?

Brian Eno – Discreet Music

Julianna Barwick – Will

Hiroshi Yoshimura – Music for Nine Postcards