Editor’s note: This article contains explicit artworks by Édouard Manet, Marcel Duchamp and Phoebe Gloeckner.

For centuries, Western art has objectified women’s bodies to fulfill patriarchal pleasure, especially since the Renaissance era. Such an ingrained ideology that elevates a masculinized perspective, while dehumanizing women in the process, normalizes the notion that female nudity is culturally acceptable. At the same time, images of naked men are viewed as inappropriate or pornographic, further supporting the hierarchical power structure that subtly oppresses women. To point out this unspoken hypocrisy and publicize the continued reality of sexual assault in domestic, familial settings, author/artist Phoebe Gloeckner offers a complex and personal examination of rape in her 1998 semi-autobiographical graphic narrative, A Child’s Life. Furthermore, she is part of a growing trend of women-authored graphic novels that are changing this medium and the larger discourse of feminism, exploring contemporary womanhood in ways that had not been broached in a cultural context before.

According to feminist graphic narrative scholar Hillary L. Chute, a notable voice in this blossoming field, Gloeckner’s contribution is profoundly important because of its impactful confrontation of sexual mistreatment. In her 2010 seminal analysis of groundbreaking author/artists Graphic Women, Chute argues that Gloeckner’s narrative stands out from other memoirs that examine such secret abuse in the domestic sphere because it embraces the inherent complexity of this dynamic. Chute claims: “Gloeckner’s work, refusing to excise titillation, is an ethical feminist project that takes the crucial risk of visualizing the complicated realities of abuse” (Chute 75). Indeed, Gloeckner not only situates her art in the ideological history of the visual, where women’s bodies are considered a mechanism for men’s sexual delight, she acknowledges the complicity that comes with this dehumanization and inherent objectification.

Presented as an autobiography of sorts, this cartoon collection repeatedly explores the experiences of Minnie Goetze, Gloeckner’s fictional alter ego, as she endures sexual assault and abuse by parental figures and peers. In addition to demonstrating the various ways in which Minnie suffers at the hands of these trusted individuals, the anthology consists of related stories with numerous characters who reflect certain facets of Gloeckner’s experiences in multiple points of view that transcend the limited experience of a young girl. Tales such as “The Girl From a Different World”, which details a teenage boy’s rejection of his girlfriend when he learns of the secret molestation in her home, and “An Evening in Prague”, detailing the troubled sexual exploits of a middle-aged woman in the Czech Republic, offer insights about the lingering consequences of assault that generate a shared story, a network of violence inflicted on women. While the central narrative focuses on what Minnie endures, Gloeckner creates a larger community of voices that enhances her readers’ understanding of the collection’s main protagonist. Divided into four sections that concentrate on stages of life from early childhood to adulthood, Gloeckner highlights the effects of sexual trauma years after the actual mistreatment occurred while offering a community of victims within these partitions. Furthermore, she adds a final chapter that includes various stand-alone drawings that span her career as a cartoonist and as a medical illustrator.

To heighten the significant connection that she builds with her readers, Gloeckner uses a number of visual methods, masterfully shaping Minnie with greater complexity and humanizing her at the same time. By interweaving conversational text and establishing steady eye contact with us during key moments of sexual abuse, we are better equipped to identify with Minnie’s despair as it happens in each frame. What’s more, the ability to look straight into Minnie’s eyes, especially in the most traumatic of circumstances, works to negate the automatic posture that instinctively objectifies female nudity. Gloeckner disrupts us from the default position of condoning Minnie’s nakedness through the customary patriarchal framework that always hovers above, ensuring we are sensitive to her sexual exploitation.

Complicating matters further, the author/artist inserts an intrinsic conflict into the conventional perspective that it’s culturally acceptable to regard female nudity as natural, an important aspect of what feminist film critic Laura Mulvey terms the “male gaze”. Indeed, the act of conforming to this ideological stance, where the sight of an unclothed female’s body may be considered commonplace, is equivalent to becoming allies with a predator. This is because the default perspective of the reader automatically reverts to the masculine, obscuring the woman’s point of view to fulfill patriarchal aims. Throughout her graphic narrative, Gloeckner points out this inherent friction, consistently reinforcing the notion that the male gaze in her recreated world signifies an acceptance of continuous, uncensored rape. In addition, her determination to accentuate this concept openly contradicts how we as viewers see ourselves. In one scene after another, she highlights situations that showcase men regularly taking advantage of the trust granted to them by young girls with no cultural consequences. Therefore, Gloeckner puts us in a pivotal position to question this patriarchal outlook during multiple encounters of explicit sexual mistreatment.

Despite the masculine veil that indirectly sanctions molestation through the societal objectification of women’s bodies, Gloeckner succeeds in breaking through this deep-rooted barrier by providing such powerful testimony. She brings her damaged protagonist to life, poignantly revealing the hierarchical structure that debases the young child’s humanity. In the process, Gloeckner offers viewers an overall awareness of sexual assault, underscoring the reality that sexual abuse of this kind takes place within domestic secrecy and further securing Minnie’s virtual imprisonment. With this intimate and emotionally mortifying spectacle of the little girl’s predicament cemented by our ever-evolving closeness, the patriarchal strings that encourage said brutality are exposed. Not only does Gloeckner demonstrate the personally destructive effect of a system that sanctions violence against women to maintain power, she solidifies our concern for Minnie as we witness her inevitable struggle to understand circumstances that are largely out of her control.

Keeping these intertwining elements in mind, this essay explores how Gloeckner deliberately shatters the fourth wall — understood both literally and figuratively — that separates Minnie from readers to develop a complex, even raw, understanding of her reality. The result is a lived experience of violence that not only confronts the normalized objectification of women in today’s rape culture, originating from art history that is hundreds of years in the making, and the masculinized power structure that allows it to persist, but demands some form of involvement from the reader. Through the repositioning of viewers from anonymous bystanders to that of responsible witnesses to brutality, Gloeckner enables her audience to question the patriarchal framework that is so often relied on in representations of sexual violation against women. In fact, Gloeckner situates her readers as active observers to significant events of mistreatment, enmeshing them in her panels with purpose. Consequently, viewers are able to testify, at least in part, to the agony Minnie endures as a victim of sexual abuse because Gloeckner exposes us to the anguish and terror of the notable scenes that she selects.

Theorizing the “Feminist Gaze” in Gloeckner’s Comics

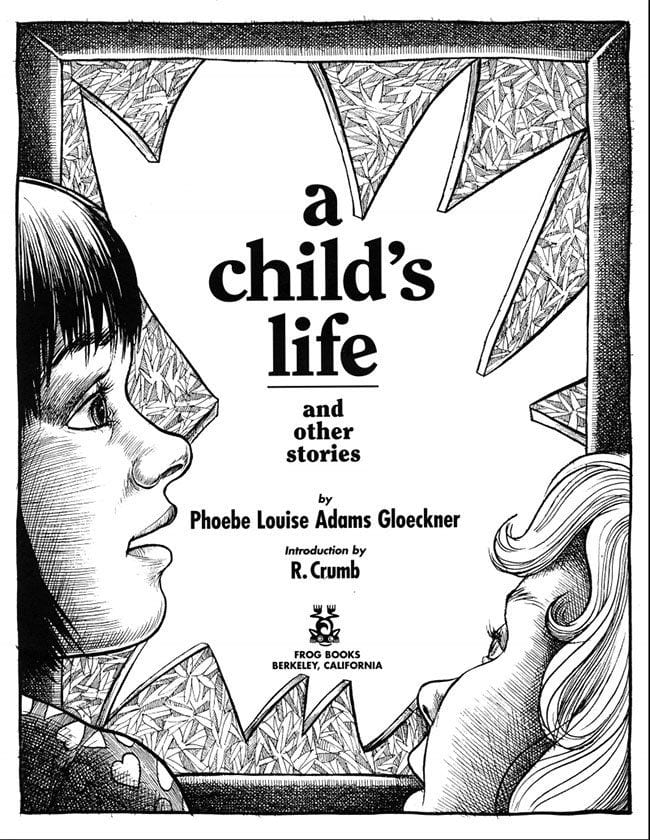

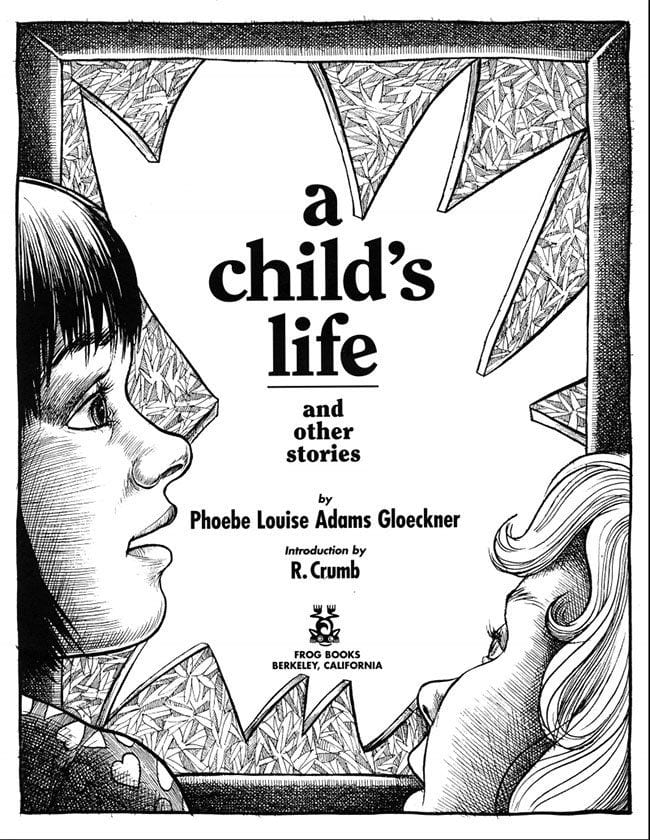

At first glance, A Child’s Life might appear to be an innocuous coloring book. This is because the comic’s cover exudes a sense of innocence. The central image shows a pale-complexioned young girl sucking candy buttons on her tongue while watching birds fly overhead. Although her profiled face dominates this picture, Gloeckner still conveys a feeling of vulnerability, a certain smallness against the faint San Francisco skyline. Her look of wonder as she observes a group of birds moving by also invites a peaceful feeling. Yet despite this tranquility, Gloeckner’s semi-fictionalized version of her formative years contains very little of the delight that the introductory picture suggests. The traumatic actuality contained within the book is masked by the charm of its cover. But there’s more to Gloeckner’s introductory image than the sweet naiveté it may suggest. Given the established tradition in the Western art world of representing youthful girls and fresh young women as sexualized fodder for a masculine audience, Gloeckner could be integrating a critique of this convention in her representation of the child’s innocent pose and the feeling of virginal sensuality.

A closer look at this image provides possible sexual signals in the young girl’s open mouth, the extension of her tongue as she savors the sugary candy and the suggestive lift of her chin. Furthermore, the narrative that this adolescent is treated as a physical commodity by trusted adults, endures regular intervals of molestation and subsequently permits sexual exploitation from various men in her life supports the possibility that this cover fits into a patriarchal artistic institution that encapsulates her as a nubile body. Indeed, famous 19th century French painters such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Édouard Manet routinely depicted the blossoming sexuality of young girls. Moreover, Manet’s controversial painting Olympia first exhibited in 1865, received a negative reception because it was originally thought to portray a prostitute due to the orchid in the youth’s hair, the bracelet and other signs of her suspected profession. However, there has since been speculation that Manet actually wanted this piece to be seen as a portrait of an untouched maiden, a young woman ready to express her sprouting sexual nature. These prominent artists epitomized and further naturalized the ideological desire for chaste, undefiled physiques in the form of appealing adolescence.

Olympia, Édouard Manet (1863)

Within this context, Gloeckner’s cover may be making a statement about how girls are culturally coded, particularly since her book illustrates the ways in which predators capitalize on these victims’ bodies. Yet Gloeckner’s potential point about the sexual exploitation of a child is not immediately evident within her book’s initial panels. Even after opening the cover, Gloeckner still maintains the illusion of harmless inexperience through her gentle, seemingly decorative title page. She shows two young girls as they stare with surprised expressions into a shattered window that reveals the book’s title information in lower-case rounded, black letters. But the enchantment we might initially perceive is misleading. The reality is that this panel contains complex implications, subtly referencing oppression, the objectification of women and voyeurism at once. Indeed, Gloeckner commences her critique of patriarchal art history by applying complex layers within this one frame, where girlhood (and by extension, womanhood) is consistently used for the fulfillment of male pleasure, to expose this invisible cultural hypocrisy.

As a result, she provides an evaluation that links comics and the visual arts in general, demonstrating the normalized objectification of women’s bodies that permeates society to this day. It isn’t until pages later that this same panel is replicated, replacing the current title information with unexpected graphic nudity of the opposite gender. Although we do not initially realize the importance of this first panel, Gloeckner sets a foundation for questioning an ideological treatment of women within this one frame. To counter the established patriarchal power that occurs merely by looking, Gloeckner visually suggests what may be called a “feminist gaze”. Not simply a reversal of nakedness, where a man’s body is on display, this feminist gaze complicates voyeuristic tendencies while accentuating the underlying, often overlooked effects of sexual abuse at the same time. Based on a reinterpretation of Laura Mulvey’s theory of the “male gaze”, Gloeckner adds a new layer of depth to this concept, further deepening the treatment of viewer position.

To demonstrate how she incorporates Mulvey’s ideas into her illustrations, it is essential to understand how this important feminist film critic perceives cultural imagery. In her influential 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, Mulvey explains that the entire perspective within movies is masculinized. From the filmmaker to the protagonist to the viewer, every perspective within this landscape remains filtered through a male vision, which showcases women as sexualized bodies, not equal players in the story. Mulvey states:

In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure, which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness. Women displayed as sexual object is the leit-motiff of erotic of erotic spectacle: from pin-ups to strip tease, from Zeigfeld to Busby Berkeley, she holds the look, plays to and signifies male desire (Mulvey 837).

According to Mulvey, women are reduced to aesthetic objects to be taken advantage of by a patriarchal culture. Since the world is dominated by masculine power, womanhood as a whole is thrust into a submissive space. Indeed, this very passivity could be construed as similar to the docile reception that the spectator routinely assumes within the darkened theater. Therefore, male sovereignty in every facet of filmmaking is extruded that much further, even concerning the default perspective of the audience. In truth, the predominant cultural mentality tends to celebrate manhood and relegate women to little more than sexual diversions. As a result, viewers are automatically expected to identify with the active/male protagonist who drives the story.

Though Gloeckner incorporates Mulvey’s powerful theory into her own work, she adds a different dimension in order to create an environment that exemplifies both masculine power and female subordination. Her expert maneuvering is particularly clear upon viewing the repetition of this introductory panel in a later picture within her collection, underlined by its provocative male sexuality. Because Gloeckner’s title page appears to function only as a method to supply the space necessary for her book’s basic information, it’s easy to overlook this panel’s commentary on misogynistic attitudes toward women. However, the frame not only initiates an assessment of cultural representations of womanhood, it also delivers a decisive foundation for the way Gloeckner situates viewers throughout her collection.

Page 2: We Are Asked to Witness

With this precursory image in place, laying the groundwork for the complicated perspective yet to come, Gloeckner ensures that the reader is effectively positioned to attest to the troubling events she illustrates in her fractured story. That is because Gloeckner blends viewership into her narrative’s initial moment, immediately constructing our prominent placement within the panels. Before we are ever formally introduced to Minnie, it could be argued that Gloeckner suggests the witness standpoint through her title page, thereby assimilating viewers into her composition. Outlined with a thick frame that surrounds the sharp edges of the broken window, both foregrounding the children’s amazed expressions in profile and locating the reader behind them at the same time, we are given a direct, firsthand look at what exists beyond the shattered pieces of glass. Therefore, Gloeckner enables us to be privy to these critical contents and to the girls’ expressions of apparent surprise as well, creating complicated layers of viewership. Already, we are thrust into a dynamic setting, doubly watching the children’s reaction while observing the source of their surprise through the smashed window.

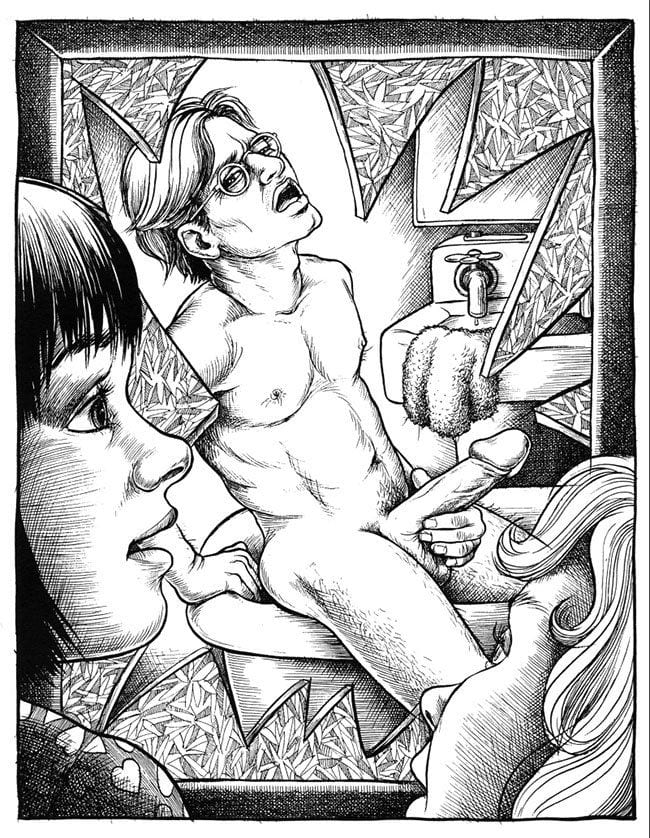

Although the full meaning of the title page is not clear until its unexpected reproduction in her brief comic entitled Hommage à Duchamp, Gloeckner’s reference to a controversial 20th century French artist remains central to her collection. Twenty-seven pages after her initial and mysterious artistic association with Duchamp, she almost exactly reiterates her opening. The only difference is that she substitutes the book’s original title information with the electrifying view of an undressed man, who happens to be the children’s stepfather Pascal, masturbating in the bathroom. Therefore, the inceptive innocence that Gloeckner conveys in the opening panel is demolished by the prominent surrogate of an erect penis. As a result, the reader’s astonishment, an emotion that could be seen as equivalent to both Minnie’s and her sister’s stunned reaction in that single moment, is further magnified by this unanticipated sight.

The complex layering at work, which appears to exhibit a contradictory conception of this nude man behind the cracked glass as both predatory and objectified, actually supports how Mulvey defines the hollow aspect assigned to women in the film world. By looking beyond this disturbingly detailed image, beneath what might be misinterpreted as pornographic, a cultural anathema, lies an intrinsic oppression of womanhood in the most basic terms imaginable. Despite the male adult’s unquestionable nakedness within this panel, the frame’s construction still insinuates that the little girls sexually excite him. So their humanity is degraded, immediately condensed into sensual devices alone, and coincides with the framework Mulvey outlines. Although Mulvey’s critique solely concentrates on the patriarchal nature of film, the ideology she offers could pertain to comics, too, because of the shared fundamental focus on visual factors. Certainly, the male gaze theory that Mulvey develops especially enriches a fuller comprehension of this particular panel. In decoding the physical eye contact actively flowing between the nude man, the young girls and us, as well as the calculated positioning within this frame, the chilling authority attributed to the masculine figure is unmistakable despite his vulnerable state of undress.

To further emphasize the crucial relevance of the panel illustrating Pascal’s inappropriate sexual behavior, it’s vital to understand that Gloeckner models this moment after a visual work entitled Étant Donnés: 1. La Chute d’Eau, 2. Le Gaz d’Éclairage by painter/sculptor Marcel Duchamp in her composition. Duchamp’s final work of modern art is famous for its manipulation of viewership. The three-dimensional installation invites people to peer through a bulky door to a private space with an extremely limited vantage point. Authors Anne d’Harnoncourt and Walter Hopps describe the environment spectators must enter to see this unorthodox diorama of mixed media. In their 1969 examination “Etant Donnés: 1° la chute d’eau, 2° le gaz d’éclairage: Reflections on a New Work by Marcel Duchamp”, they explain this unique setting in vivid detail:

The visitor passes through a doorway in the far corner of the gallery and turns to find himself in a small room, confronted with a roughly stuccoed wall extending across it from floor to ceiling and from wall to wall. In the center of the stucco wall is a large arched doorway made of old bricks, framing an old Spanish wooden door… The door is a weathered silver gray, studded with iron rivets, with no sign of hinges or of any knob or handle, which confirms the impression that it cannot be opened. In the middle of the door, at eye level, almost invisible from a distance, are two small holes. If the visitor accepts the invitation and strolls up to peer through the holes, the first shock of encounter with the scene behind the door will always be a private and essentially indescribable experience (d’Harnoncourt and Hopps 8).

Étant donnés, Marcel Duchamp (1946–1966)

Based on this description, it’s clear that the viewer needs to make more of an effort to achieve a deeper understanding of Duchamp’s piece. Spectators cannot see this installation without taking obvious steps to gain access to the pair of small peepholes. Once the viewer reaches this point, a pastoral scene that contains a provocatively positioned nude woman is visible in the foreground. Because of the eclipsed surroundings, where the observer can only absorb fragments of the suggestive panorama, a forbidden mood is perpetuated by peering into this atypical setting. The viewer’s subsequent embarrassment comes from gazing into this private place without permission. Indeed, no warning is ever offered to inform guests that a completely bare woman can be seen stretched out, her vaginal area immediately noticeable, beyond the plain farm door. Yet just by looking into this secret world, the viewer becomes incorporated into the environment as a voyeur, imposing a violent stare in anonymity. This installation could even be described as the equivalent of a peep show that’s designed for the explicit pleasure of men. Therefore, Duchamp assigns the observer a role that moves from passive spectatorship to an active violator of a vulnerable woman’s seclusion from the public. To be sure, the artist’s viewers actually become part of the startling sight that exists inside the jagged holes, reinforcing the fascination. In that instant of piecing together the chamber’s salacious contents, the innocence of regarding art is transformed into an apparent trespassing. Indeed, the viewer invades the nude figure’s world with one gesture of intrusive curiosity.

Purposely lacking any fanfare, the outer wooden door does not hint at the composition behind its plain appearance. So the unsuspecting viewer cannot anticipate the figure of a naked woman sprawled on a bed of twigs and holding a gaslight in her outstretched hand before a painted landscape. To be sure, Duchamp’s sculpture inspires a series of questions about the potential violences and violations that are assumed in the role of the spectator. Although viewing is often taken for granted in museum settings and other public, even private places, Duchamp poses that the process of looking, however harmless it may seem, could be interpreted as a conceivable invasion. Quite contradictorily, though, he defuses his audience’s visual power to disrupt by restraining the vantage point through the peepholes alone. Therefore, a complete perspective of this intricate work is always elusive.

We are wholly independent, with no corporate backers.

Simply whitelisting PopMatters is a show of support.

Thank you.

Dalia Judovitz examines the complicated position Duchamp appoints to onlookers in her 2002 article “De-Assembling Vision: Conceptual Strategies in Duchamp, Matta-Clark, Wilson”. She observes that Duchamp’s work is an elaborate statement on voyeurism designed both to delay the visual pleasure art conventionally provides viewers on an instantaneous basis and mock spectatorship as an objectification of subject matter in general. Similar to the response of previous critics, Judovitz observes that the viewer becomes part of the display, an aspect that Duchamp integrates as crucial to his critique. Expanding on this point, Judovitz states:

The spectator’s intrusive gaze that seeks to probe the reality of sex is projected back upon itself, thus becoming itself the object of scrutiny. The violence of this work appears to lie less in its manifest sexual exhibitionism and voyeurism, than in the fact that the spectator is put face to face with his or her desire to look, to be fascinated by the consumption of sexuality as an image (Judovitz 102).

In other words, Judovitz claims that Duchamp situates viewers so that they become aware of their own intrusiveness. By making the choice to survey the room’s interior, the observer’s curiosity is judged in a critical light. Consequently, the viewer is no longer unidentified, but acknowledged as a party to the imposition of the nude figure’s assumed solitude. To complicate the effect further, this anonymity only exists to the objectified woman. But in relation to the other visitors experiencing this exhibit, the viewer’s unknown presence becomes lost. This is because the spectator can be seen peering into those peepholes by nearby patrons. So the voyeuristic pleasure that is derived from secretly watching an unsuspecting person transforms into something more akin to shame or humiliation.

In essence, the artist forces viewers to recognize their need to look, effectively confiscating the pleasure derived from not being identified while indulging in the common practice of gazing. Consequently, Duchamp adds layers of complexity to the actual definition of a spectator. He assigns responsibility to the bystander, demonstrating that the practice of devoting attention to such a sexualized scene only reinforces the societal violence it represents. Although no tangible contact is ever made in this encounter, the person who peers into the pair of eye holes still engages in an intimate moment that the woman has no power to refuse. Indeed, Duchamp articulates a personal involvement in our cultural preoccupation with sexuality, which often translates to voyeuristic infringement. Furthermore, as Judovitz notes, Duchamp’s decision to weave the viewer’s stare into his unusual setting brings an invisible yet undeniable transgression to the artwork, proving that just the act of observing has a physical, often brutal presence.

To Jindřich Chalupecký, however, the patron of this unusual exhibit should not be entirely blamed. Duchamp encourages the visitor’s participation in an ongoing attempt to compel active viewership of art. It’s no accident that spectators have to make an effort to obtain the full effect of Duchamp’s sculpture. In Chalupecký’s 1985 essay “Marcel Duchamp: A Reevaluation”, he discusses how the artist concentrated on discovering innovative ways to manipulate the observer’s vantage point. According to Chalupecký, Duchamp formulated his three-dimensional piece to alter how visitors behaved in exhibitional spaces. His last and probably most celebrated work was not the first time he had fashioned a peephole to entice his guests to peer inside. But with this final sculptural work, Duchamp extends his previous experimentation to generate the effect he had been pursuing for so long. To be sure, the artist beckons viewers by reshaping the traditional museum display, thereby ensuring that the act of witnessing becomes an unanticipated activity. Chalupecký states that Duchamp fuses this intentional outcome into his last artwork, “…which can only be seen through a peep-hole in an old wooden gate. The viewer must confront the work alone. He can no longer judge it ‘esthetically’, as an extension of his normal visual environment. The work is elsewhere, and the viewer too must find himself with it elsewhere” (Chalupecký 134). Therefore, Duchamp challenges people who approach his work to rethink how art functions, politicizing the act of looking to signify its gendered reality, where women are reduced to objects simply by the viewer’s intrusive gaze.

With its widely discussed yet still ambiguous approach to spectatorship, Duchamp also assigns his 1966 three-dimensional sculptural artwork an enigmatic name, which, translated from the French, means: Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas. This title identifies the physical elements of the sculpture in straightforward terms without acknowledging any aspect of Duchamp’s cryptic purpose. Yet in keeping with the bewildering nature of this installation piece and its ultimate reliance on the viewer’s perspective, the artist’s decision to restrict the wording to mere objects alone only adds to the fascination. Even more importantly, the title misleads, which is the effect that Gloeckner also achieves with her comic dedicated to Duchamp’s installation. In a move that both emphasizes and enhances the sculptor’s multi-dimensional message, Gloeckner’s title page image offers her own interpretation of Duchamp’s celebrated artwork in its integration of viewership. While providing a impactful commentary on her readers’ existence, subtly acknowledging our presence because of how we are situated behind the two surprised children, Gloeckner previews one of the most pivotal, full-page frames of her book, where sexual trauma first appears. Although the viewer may see the opening frame as a simple design element, unaware of the foreshadowing of the abuse to come, Gloeckner subtly establishes the exceptional demands she will impose on her viewers to make sense out of this fractured story of violence.

Through her translation of Duchamp’s deliberate viewer positioning, Gloeckner enables a firsthand look of the young girls’ shocked interest as well as offering a glimpse into the peek hole of the broken window. With the same careful detail, Gloeckner demonstrates that viewers are merged into her visual work. Yet the author/artist swerves away from Duchamp in the sense that she provides her own spin on our role as readers. Seized from the shadows, she assigns a significant amount of accountability to us without the supposed judgment that Duchamp reflects within his sculptural piece. In contrast, Duchamp designs his diorama to elicit guilt from viewers who take the trouble to peer into what might be seen as an intimate moment. Gloeckner, however, does not take this disapproving tone. Instead of criticizing viewers, silently scorning those who are drawn to art as voyeuristic, she reaches out to her audience in order to confirm the abuse. We are asked to witness, to attest to the despicable brutality that Minnie, the child located on the panel’s left side, must endure in the secluded domestic sphere, inaccessible to anyone except close family members.

To add an even more intricate layer to Gloeckner’s image, it could be said that Pascal actually forces both the children and the viewer to become voyeurs. By continuing to touch himself after being discovered and proudly maintaining eye contact in the midst of this activity, it could be argued that Pascal has created a scenario to showcase his actions. Because of this sustained glance, which may be aimed at the girls and the reader, any sense of intrusiveness on the part of the observers is negated. By referencing Duchamp’s final masterpiece and elevating it to such a predominant focus in her narrative, Gloeckner adds multiple levels of complication, both critiquing the normalized acceptance of naked womanhood and simultaneously intermixing intense discomfort.

Page 3: Depiction of the Sexually Engaged Predator

Furthermore, she replaces Duchamp’s nude female with a completely unclothed man engaged in pleasuring himself, thereby inducing shock at such a reversal while also pointing out the cultural resistance to male nudity. It’s rare that a man’s body is represented in such a sexualized manner within the context of Western art. So Gloeckner forces her readers to acknowledge their mortification, which stresses the presence of this double standard. To enhance the baffled perplexity, Gloeckner exaggerates the man’s phallus in size, aligning it almost perfectly with the surprised glance of Minnie. Such a layout draws attention to the most alarming aspect of this scene, appropriately startling the youths and the reader alike. Strengthening this complex composition even further, we are situated behind the juveniles, which allows us to sustain a clear view of their open-mouthed posture as well as the stimulated man from within the broken window. The result of this deliberately orchestrated positioning is that we feel an emotional connection to the two girls, an empathic closeness derived from their obvious vulnerability in this unnerving instant. Because of the way Gloeckner has located our vantage point in this panel, there’s no distance in the spectacle, which allows us to experience the trauma in a very personal manner.

The mix of feelings that Gloeckner evokes both enhances her complex criticism of the cultural handling of gendered nudity and stirs questions about the systemic objectification of womanhood in the art world and beyond. Indeed, Gloeckner’s decision to centralize the conspicuous image of a man’s fully erect penis, modeled after Duchamp’s diorama, summons a host of elaborate, interconnected feminist issues. To gain a deeper understanding of the work Gloeckner performs within this single frame, it’s important to get a broader perspective of how Duchamp’s installation uncovers dominant power structures. Julian Jason Haladyn touches on these insights, delving into terrain that explores the patriarchal mindset concerning women’s bodies and the intrusiveness that results. In Haladyn’s 2013 article “A Contribution to the Study of the Fantasies of Sexual Perversion in Marcel Duchamp’s Etant Donnés” he discusses how the artist manipulates female nudity to make a statement about the voyeuristic experience. Haladyn admits that the notion of fantasy in relation to Duchamp is rarely examined. For the most part, Duchamp is known for putting everyday objects on display such as a shovel or a urinal and designating them as art. Through this act, Duchamp is, in effect, playing with the spectator by testing whether or not the placement of these items in a museum space constitutes a genuine, acceptable work. According to Haladyn, Duchamp incorporates the idea of context into the fantasy of Etant Donnés or Given, where the setting defines how artifacts are viewed. The author explains that there are certain pieces within this outlined area, but the underlying foundation is forever missing. Haladyn equates this sensation with the way Duchamp treats his viewers in the creation of Given. Indeed, he provides a fantasy that we are never able to experience in its entirety by nature of the peepholes. Additionally, Haladyn points out that we cannot interact with the elements that constitute this assemblage because they are locked behind a door, which leaves us with unfinished perceptions.

Expanding on Chalupecký’s insight about Duchamp’s carefully constructed space, Haladyn explains that viewers are forced to undergo a process in order to see what’s secured behind the barn door. He further states that unlike traditional paintings of nudes in a museum, permitting the observer to attain the full picture from any number of angles, Given only allows a limited view of the naked subject from a specific position. Moreover, upon peering through the eye holes, we are instantly confronted with the woman’s sexual organs, an act that, Haladyn argues, is key to the encounter:

Beyond the realism of the figure in Given — as well as the strangeness of the fantasy environment in which we find her — the immediate image that awaits us on the other side of the door is the female genital apparatus. It is the experience of seeing this vision that viewers do not want to confess to. This display of sexuality, or more precisely sexual difference, is the root of viewers’ discomfort and shock when experiencing Given

(Haladyn 6).

Even though Duchamp has carefully created this peepshow environment, never including any prior warning, it is the visitor who is humiliated by such an intrusion upon being noticed by others after peeking into the eye holes. Interestingly, Gloeckner mimics this same disturbance in her interpretation of Given by placing an erect penis at the center of her panel. Yet while the viewer’s focus promptly lands on the exaggerated depiction, the nude man appears to enjoy this acknowledgment, never offering any hint of indignity. It’s as if he welcomes our presence. Furthermore, in a move that is opposite to Duchamp’s, who intentionally conceals certain aspects of the woman’s body, restricting a full view, Gloeckner does not limit the spectator from experiencing a complete perspective of this scene. Indeed, Duchamp commands his visitors to walk into a separate space and spy through a pair of small-scale holes in order to see carefully chosen aspects of this diorama, but Gloeckner has no such barriers. Every detail is out in the open. Still, the shock value of her rendition seems to be the equivalent in its intensity to Duchamp’s nonetheless. Perhaps this can be explained by the fact that general female nudity, with the exception of Duchamp’s positioning of the nude in Given and the manufactured environment that viewers must enter, is naturalized. In contrast, masculine nakedness often inspires greater cultural resistance due to the patriarchal power structure operating beneath the surface.

However, the message that Gloeckner conveys goes beyond the hypocritical treatment of gendered nudity, offering a nuanced alternative to and a critique of the patriarchal manner in which women’s bodies are viewed. With the use of Duchamp’s installation as an ironic model, Gloeckner creates a feminist gaze that both highlights the inherent contradiction between representations of male and female nudity and showcases the violence of sexual abuse at once. By replacing Duchamp’s naked woman, who is unaware of the spying spectator, with a nude man, who meets the girls’ and the reader’s stare while continuing to masturbate, Gloeckner embeds a meaningful complication to this image. Indeed, Gloeckner’s sexually engaged adult is not a reversal of Duchamp’s unsuspecting woman, but the embodiment of predatory behavior. What’s more, despite his bareness, he is the real intruder, the violator of trust, which could be construed as paradoxical since his naked body remains so centrally displayed.

In order to navigate this complexity and understand the multiple facets that are functioning in unison within Gloeckner’s panel, Haladyn provides an insightful foundation. His analysis of the violation that occurs when peering at Duchamp’s unclothed woman is key to comprehending the patriarchal mindset that Gloeckner criticizes. Haladyn discusses the erotic fantasy that Duchamp creates through the mood he assigns his installation, where viewers must enter a dimly lit room to gain access to a sight of the incognizant nude figure. Furthermore, unlike Gloeckner’s panel, where the sexuality is graphic, Duchamp’s subject, while situated in a spread eagle position, lacks genitalia since only the suggestion is provided in the artist’s depiction. Haladyn observes that “…within this explicit shock of the literal…staged within Given, there is a notable absence of a realistically depicted vagina. Within the relative realism of the assemblage… the woman’s sex is shockingly unreal… The absence of a realistically depicted vagina in Given is literally overlooked and in its place a fantastically envisioned provocative sexual organ looks up” (Haladyn 6).

In order to navigate this complexity and understand the multiple facets that are functioning in unison within Gloeckner’s panel, Haladyn provides an insightful foundation. His analysis of the violation that occurs when peering at Duchamp’s unclothed woman is key to comprehending the patriarchal mindset that Gloeckner criticizes. Haladyn discusses the erotic fantasy that Duchamp creates through the mood he assigns his installation, where viewers must enter a dimly lit room to gain access to a sight of the incognizant nude figure. Furthermore, unlike Gloeckner’s panel, where the sexuality is graphic, Duchamp’s subject, while situated in a spread eagle position, lacks genitalia since only the suggestion is provided in the artist’s depiction. Haladyn observes that “…within this explicit shock of the literal…staged within Given, there is a notable absence of a realistically depicted vagina. Within the relative realism of the assemblage…the woman’s sex is shockingly unreal…The absence of a realistically depicted vagina in Given is literally overlooked and in its place a fantastically envisioned provocative sexual organ looks up” (Haladyn 6). Based on Haladyn’s description, it might be said that the fantasy of seeing something that is customarily viewed as private, which the viewer perceives by the manner in which Duchamp presents his piece, matters more than the objectified woman.

But this seductive envisioning may radiate even beyond the figure’s insinuated vagina. Michael Asbury suggests the erotic nature of Duchamp’s nude woman derives primarily from conceiving her sexual circumstances. In his 2011 article “Daniel Senise, 2892: Between Being and Nothingness, the Spectator,” Asbury proposes two different sexual scenarios for Given that offer the possibility of patriarchal appeal. He states that the outstretched woman “…could either be experiencing ‘the moment of fulfillment’ or lying there, perhaps even dead, after an episode of violation” (Asbury 128). These alternative readings enhance the objectified status of this figure, transforming her into a more concrete fantasy based on stereotypical masculine scenarios that heighten her sexuality. Furthermore, such ideas raise the distinct possibility that this figure is not simply nude, but, perhaps, in a state of arousal. Although sexual stimulation is not always apparent in a woman’s posture, unlike a man’s, Asbury does theorize that Duchamp’s female nude might express physical excitement, thus, strengthening the credible comparison between this naked woman and Gloeckner’s masturbating male. In addition, whether it’s the blatant nonexistence of vaginal detail or an imagined situation that centers on the aftermath of sexual intercourse, welcomed or not, hackneyed musings driven by patriarchal features could explain why viewers are drawn to the installation. As a result, sexualized impressions overtake reality and objectify Duchamp’s subject, thrusting voyeurism above the rights of the figure behind the peephole.

To elucidate this fundamental intrusion further, Haladyn compares Duchamp’s invasive setting to Jean-Paul Sartre’s classic analysis of looking in his 1943 philosophical masterpiece Being and Nothingness. In Haladyn’s view, Sartre is a critical tool for deciphering Duchamp’s decision to incorporate eye holes so that his installation can be experienced from a particular vantage point. Haladyn specifically cites Sartre’s example of an individual staring through a keyhole in a door as crucial in the context of Duchamp’s construction. Sartre writes:

Let us imagine that moved by jealousy, curiosity, or vice I have just glued my ear to the door and looked through a keyhole. I am alone and on the level of a non-thetic self-consciousness… This means that behind that door a spectacle is presented as “to be seen,” a conversation as “to be heard”…But all of a sudden I hear footsteps in the hall. Someone is looking at me! What does this mean? It means that I am suddenly affected in my being and that essential modifications appear to my structure — modifications which I can apprehend and fix conceptually by means of the reflective cogito…It is this irruption of the self which has been most often described: I see myself because somebody sees me — as it is usually expressed (Sartre 347-349).

Using Sartre as a lens to translate Duchamp, the individual who looks inside that hole in the door indulges in the temptation to spy on someone with self-conscious emotions already present. But the urge to peer, to see what secret activity exists behind the door, outweighs any decency to refrain from such an evident violation. Once the eavesdropping person hears footsteps coming down the hall, then the shame of peeking through that tiny hole erupts within the self. In essence, this is the recognition that Duchamp stirs through the orchestration of his assemblage.

According to Haladyn’s thought process, he believes Sartre builds a “…voyeuristic fantasy environment that is given specifically ‘to be seen’ without consequences — similar to the collective alibi of viewing within the museum context” (Haladyn 5). In other words, there’s a parallel between the voyeuristic tone of Duchamp’s exhibit and Sartre’s private spying through the keyhole. Both assign mortification to the act of being discovered after looking at an unaware subject and, thereby, losing the security of anonymity. But this alarmed self-knowledge happens in different forms. For Duchamp, such embarrassment derives from the viewer’s sudden perception that the peephole leads directly to a naked woman’s genitals. Sartre, on the other hand, creates discomfort by the approach of footsteps, epitomizing how the viewer promptly feels caught in the act of doing something immoral. Furthermore, Haladyn distinguishes between the two scenarios by pointing out that Sartre’s fantasy is the erotic suggestion of what could be on the other side of the keyhole whereas Duchamp provides an actual salacious scene. He writes: “The content of this fantasy, which depends greatly upon the way in which it is produced, is primarily based within what is displayed, but the content displayed — a nude female with her legs spread — reciprocally affects the manner in which the staging is experienced. Unlike Sartre’s voyeur who is unable to see beyond the keyhole, with Given we see the content of what is behind the door: we witness the hidden fantasy” (Haladyn 5). Although the visibility of the objectified subject differs, depending on the artist or author, the fact is that both circumstances highlight the violation caused by the voyeur.

Along these same lines, Steve Martinot reiterates the keen awareness that the viewer experiences upon committing this violence. In his 2005 article “The Sartrean Account of the Look as a Theory of Dialogue”, Martinot acknowledges the humiliation that results from such visual intrusions. He states: “The look is always accompanied by shame — the shame of having been rendered an object… The content of this relation may indeed be morally shameful, such as being caught peeping through a keyhole, but it is not restricted to such situations.” Therefore, as soon as the viewer is noticed by someone walking up from behind, the former spy becomes the object. But one of the most significant aspects of this truth is that these remorseful emotions only occur when the voyeur is noticed by the person advancing from down the hall. Luna Dolezal explores this point further in her 2012 article “Reconsidering the Look in Sartre’s: Being and Nothingness”, where self-awareness and judgment manifest in palpable form. According to Dolezal’s interpretation of Sartre’s stance on looking, dehumanization occurs upon receiving the gaze. She notes: “The Look for Sartre is not merely about being within the other’s perceptual field; it is not a neutral seeing, but rather, it is a value-laden looking which has the power to objectify and causes the subject to turn attention to him- or herself in a self-reflective manner. When I am looked at by another, I am reduced to an object” (Dolezal 15). From a feminist perspective, the woman subject is robbed of her humanity upon feeling another’s look. Instead of being a full-fledged individual, she is transformed into an object, viewed as simply a device for the sexual pleasure of men. Echoing Martinot, Dolezal explains that by receiving another person’s gaze, the woman is diminished to the degree that she is no longer an equal human being. This is the effect that’s transferred onto the phantom erotica inside Sartre’s keyhole and the nude woman that awaits in Duchamp’s diorama.

Page 4: Defying the Unspoken Taboo

The notion of objectification that Dolezal perceives lends itself directly to the process both Minnie and Pascal undergo in Gloeckner’s Duchamp-inspired panel. Within the framework created by the sculptor, the child and the grown man are each looked at by the other, imagined and embodied as objects to different extents. In one sense, it could be said that Minnie objectifies her stepfather as a spectator to his sexual activity. Yet despite the reality that Minnie is, in fact, a witness somehow overlooks the power relations at stake during this key moment. Although Minnie is fully clothed and not engaged in any sexual activity, Gloeckner still positions her as the object in this scene. The authoritative Pascal’s line of sight leads right back to her while he continues to indulge himself. Thus, ironically, Minnie appears to be an inspiration for sexual satisfaction, even though the image of an unmistakably naked man is central to this peephole. Initially, it seems that Pascal is objectified, reduced to a physical display, due to his indisputable and unencumbered nudity. But when the layers of rigorous complexity are removed, Minnie occupies this powerless role. Once she is aware of Pascal’s look, she becomes objectified in the worst possible way. Indeed, to receive her stepfather’s glance almost guarantees mistreatment of some sort in the future.

How Western Art Promotes and Normalizes Female Nudity

Applying the foundation that Duchamp executes and Sartre describes does provide significant insight into the complex circumstances Gloeckner illustrates in this one panel. While our intimate placement just beyond the frame’s borders enables a clear picture of the children’s abusive predicament, other meaningful facets exist such as the cultural hypocrisy attached to Western art’s historical representations of nakedness. This particular drawing offers a fierce critique of the gendering of nudity, where images of unclothed bodies are normal when women are featured, but controversial when men are the subject. Due to the saturation of female sexuality in contemporary times, the idea of displaying a woman’s bare form seems almost banal. Indeed, our culture is inundated with imagery that depicts womanhood in primarily sensual terms. This reduction of women to bodies alone for the sake of sexual pleasure can be seen as a profound contradiction considering the fact that, in general, men are not diminished as carnal objects. The 1972 feminist study of visual culture Ways of Seeing by John Berger explains why women’s sexuality remains such a massive preoccupation in our patriarchally-oriented society, especially through the filter of Western art history.

As groundwork for the long-standing acceptance of the painted nudes of female subjects in European art, Berger explains the conventions that justify how women have been viewed as sights. But Berger clarifies that this reasoning pinpoints the fundamental patriarchy at work. “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, you put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure. The real function of the mirror was otherwise. It was to make the woman connive in treating herself as, first and foremost, a sight” (Berger 51). This concept is vital to discussing the historical pathway for transforming women into a vision for men to enjoy, overriding their role in art as anything but bodily fantasies. Berger takes this judgment to an even more pronounced level as he concentrates on the nature of individuals deemed as viewers of Western art:

In the average European oil painting of the nude the principal protagonist is never painted. He is the spectator in front of the picture and he is presumed to be a man. Everything is addressed to him. Everything must appear to be the result of his being there. It is for him that the figures have assumed their nudity. But he, by definition, is a stranger — with his clothes still on (Berger 54).

Indeed, Berger makes it very clear that the practice of painting nudes has been constructed around pleasing male spectators for centuries. Therefore, in this context, women’s bodies become instruments that offer visual delight to an audience of men. In other words, women as painted objects are deprived of an identity other than stimulation for male viewers.

Interestingly, Berger observes that even though the spectator is not actually seen in the painting’s composition, he still holds the reins, controlling the content from beyond the canvas. As a whole, this patriarchal marketplace dictates what is culturally desirable and acceptable to be seen. Moreover, Berger stresses that the established ideology that minimizes the female form into visual entertainment does not merely refer to a painting tradition of years past. It operates to this day, applicable to other types of media such as television shows, news reports and advertising. Berger concludes by claiming that “…the essential way of seeing women, the essential use to which their images are put, has not changed. Women are depicted in a quite different way from men — not because the feminine is different from the masculine — but because the ideal spectator is always assumed to be male and the image of the woman is designed to flatter him” (Berger 64). To be sure, Berger is providing the infrastructure for how images of nude female figures have been naturalized for generations. His observation puts Gloeckner’s battle to uncover this deep, cultural bias into both words and images, divulging the colossal tenets that she confronts in her comics that develop a feminist gaze.

Despite the fact that the default male spectator, as Berger explains, determines the normalization of feminine nakedness, the obvious lack of men’s nudity in mainstream culture raises questions that deserve further exploration. Suzanne Moore considers the hypocrisy of shielding men in an undressed state while the sight of unclothed women is regarded as acceptable. Her chapter “Here’s Looking at You, Kid!” in the 1988 feminist analytical work, The Female Gaze: Women As Viewers of Popular Culture examines what underlies this discrepancy. Moore even admits her own difficulty in finding an obvious explanation for the dramatically different treatment of nudity, depending on gender. She claims there is an abundance of information about the way men look at women’s bodies, but the opposite circumstance reveals an eerie silence as far as her own research is concerned. Fascinatingly, her observation can be connected to Berger’s insights, providing solid support for his theory that disrobed men are not visually represented because they regulate the distribution of cultural imagery. Moore reiterates Berger’s declaration by saying that “…to suggest that women actually look at men’s bodies is apparently to stumble into a theoretical minefield which holds sacred the idea that in the dominant media the look is always already structured as male” (Moore 45). This scrutiny indicates that an unspoken cultural reason can be accountable for such a glaring inconsistency, which is patriarchally coded and persists with very little attention. Therefore, the invisible reality of male superiority in our society enables this mindset to prevail. Later in her essay, Moore offers an explanation for this cultural contradiction that parallels Berger: “Explicitly sexual representations of men have always troubled dominant ideas of masculinity, because male power is so tied to looking rather than to being looked at” (Moore 53). By reserving the presence of nakedness virtually to women’s bodies alone, the established patriarchal framework is not threatened and enables this power structure to remain undisturbed.

At the end of Moore’s chapter, she concedes that the attitude toward men in a state of undress is slowly becoming more permissible from a cultural standpoint. Despite some progress on this profound inequality, though, Moore claims there is a clear border that silently prevents certain types of male nakedness from crossing over to receive a favorable reception in terms of popular culture. She states: “So although in some contexts the male body is being legitimized as an object of desire, explicit portrayals of the male genitals are still forbidden. An erect penis is still what makes hard porn ‘hard’. The right is ever more frantic to preserve its phallic mystique — the erect penis is still supposed to be an object of mystery rather than a bit of disappointment…” (Moore 59). To be sure, the act of showing men’s sexuality in full effectively undermines patriarchal authority, placing men’s sexuality on display and enabling the passive role as object.

For this reason, imagery that depicts such nudity is ideologically seen as undermining masculine power structures. Lynda Nead confirms this unspoken notion in her 1990 article “The Female Nude: Pornography, Art and Sexuality”, reflecting the cultural control over exhibiting women’s naked bodies that enables images of men in any controversial state of undress to be exempt. But Nead also offers complex readings on how art and pornography often intersect and diverge, depending on the cultural boundaries that are in place at the time. Most importantly, however, she insists that the line between art and pornography is thin, nuanced by understated distinctions that serve to permit both forms of female nudity to coexist within our patriarchal society. According to Nead, some critics distinguish the two types of representations as sensual and sexual, signifying high culture and low culture. In the end, though, patriarchal domination seemingly justifies each category of representation for the sake of male supremacy, warranting this kind of visual pleasure for cultural consumption without defining any true limits beyond cursory ideas of what is and what is not respectable. Nead explains that despite the cultural arguments about whether or not one type of nudity is more admissible than another, the two are strikingly similar in terms of how women’s bodies are both portrayed within such an entrenched system. Demonstrating that classifying female nudity is immaterial because they each denote the oppression of women, Nead states that:

…the female nude is not simply one subject among others, one form among many, it is the subject, the form. It is a paradigm of Western high culture with its network of contingent values: civilization, edification, and aesthetic pleasure. The female nude is also a sign of those other, more hidden properties of patriarchal culture, that is, possession, power, and subordination. The female nude works both as a sexual and a cultural category, but this is not simply a matter of content or some intrinsic meaning. The signification of the female nude cannot be separated from the historical discourses of culture, that is, the representation of the nude by critics and art historians. These texts do not simply analyze an already constituted area of cultural knowledge, rather, they actively define cultural knowledge. The nude is always organized into a particular cultural industry and thus circulates new definitions of class, gender, and morality. Moreover, representations of the female nude created by male artists testify not only to patriarchal understandings of female sexuality and femininity, but they also endorse certain definitions of male sexuality and masculinity (Nead 326).

Therefore, Nead claims that the separation of female nudity into art and pornography really doesn’t matter. The act of showcasing a woman’s naked body broadcasts power dynamics that are not muted by perfunctory divisions. At the very heart of the normalization of nude female forms is an ingrained hierarchy. In essence, patriarchal forces ensure male power is never diminished by images of societal vulnerability.

To counter this noted absence of the unclothed male form that Nead identifies, it’s feasible to observe that Gloeckner confronts such discriminatory cultural boundaries through her comics. In truth, she displays sexualized male bodies with an intense rawness, refusing to allow the unspoken taboo to stop her from illustrating highly charged subject matter. Demonstrating this determination, feminist comics scholar Hillary Chute discusses Gloeckner’s courage to defy convention and present images that violate how masculinity is supposed to be seen, which, just as Moore predicted about such representations, has immediately received a pornography label. In her 2010 acclaimed book Graphic Women, Chute provides a pertinent history of A Child’s Life noting, among other pivotal details, how the publisher had to cut ties with its original and longtime printer and quickly find a replacement due to a corporate misreading of Gloeckner’s drawings. Still, the new printer only agreed to work on the comics collection after work hours. Chute explains the obstacles Gloeckner’s first graphic narrative faced:

Images of sexual acts, and oftentimes images of menacing, enlarged genitals are prevalent in A Child’s Life. Most mainstream bookstores do not carry Gloeckner’s work… Gloeckner is wary of the idea that what people react to with fury in her work is an erect penis, rather than to the intimate images of degraded women that have now become so culturally familiar (Chute 68).

It’s evident that the content of these pictures, which refuses to apologize for its visual candor, overshadows Gloeckner’s message about the trauma of molestation within popular culture’s limited framework.

Similarly, the fixation on men’s genitalia rather than the heinous abuse inflicted by predatorial parental figures is one of the subjects of New York Times reporter Peggy Orenstein’s 2001 interview with Gloeckner entitled “A Graphic Life”. Orenstein observes that the author/artist struggles with the overall dismissal of her work as pornography because it misrepresents her intent. According to Orenstein, Gloeckner wants to expose the terror ingrained in child abuse and cannot understand why the dominant culture refuses to see that she is tackling sexual mistreatment, not generating pornographic entertainment. Nead’s insights about the cultural murkiness between art and pornography could be applicable here except from a vastly different angle because the exposure of men’s bodies is at issue. Due to Gloeckner’s unabashed illustrations of male nudity, which could be seen as undermining patriarchal authority, a pornographic label is the most obvious way to discredit her art. Furthermore, it conveniently overlooks the message behind her polarizing images. To convey the author/artist’s true intent in producing this comic collection, Orenstein writes: “Gloeckner describes her creative process as a wrestling match between the compulsive demands of her own vision and a fear of those who might label it ‘dirty.’ There’s the voice of her publisher, who has — no pressure — mentioned that without the images of erect penises, her books would be easier to market” (Orenstein 29). Again, threads of Moore’s argument about the cultural deficiency of naked masculinity are supported by Gloeckner’s direct experience in her attempts to smash through such a reinforced wall against these depictions.

Page 5: Uncensored Detail

Indeed, the wide acceptance and deserved celebration of Gloeckner’s work continue to be systemically withheld because she dares to objectify a man’s body and illustrate sexual assault. Even though her goals center on an honest exploration of sexual mistreatment, the misplaced obsession with illustrations of male genitalia obscure what she’s truly trying to convey. Gloeckner herself has expressed frustration with this obvious societal blind spot. As a response of sorts to her critics, she blasts the condemnation that she has received for representing manhood in a way that’s equivalent to accepted images of women’s nudity. In a 2003 online interview with media writer Sean Collins, Gloeckner openly shares her rage at the obvious contradictions that prescribe how the body can be represented in societal terms, depending on gender:

…you can show a woman with her legs spread and some spray on her to make her look like she’s all hot and bothered, right? And then you can’t show an erect penis. I mean, tell me why? I’ve said this before, but, a man can pick up Playboy and see a beaver shot and jerk off on it thinking, “Oh, she wants to get fucked”. But Playgirl magazine has flaccid penises. I mean, who’s gonna pick that up and think, “He wants to fuck me”? You’re not. I think those laws were made because men are homophobic and also afraid of women’s sexuality. It’s men who make those laws. It’s really totally arbitrary and doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. And so the sexuality has been kinda trained out of women and homosexual men in our society. It’s not expressed. Maybe it’s beginning to be expressed. Anyway, this pisses me off. That’s why… I’m fighting against it, and… I hope I’m not the only one.

To be sure, Gloeckner reveals a troubling point in her frustration at this evident contradiction between how men’s and women’s bodies can be visually depicted within mainstream circles. In fact, the resistance to imagery which delineates erections can serve to mask the cultural realities of sexual abuse that women endure everyday, effectively making this truth invisible to the general public. Further expanding on this notion, Hillary Chute underscores Gloeckner’s outrage about the paradoxical constraint against representing explicit male sexuality. In her pioneering analysis Graphic Women, Chute explains: “Gloeckner is wary of the idea that what people react to with fury in her work is an erect penis, rather than to the intimate images of degraded women that have now become so culturally familiar” (Chute 68). Therefore, such indignation for phallic images is not merely a distraction from the actual inhumanity within these illustrations, but a way of normalizing the violence. Indeed, this analysis directly relates to Orenstein’s observation that Gloeckner’s collections would be simpler to place on bookstore shelves were it not for the unequivocal manhood on display. According to cultural standards, these imaginative representations are more offensive than the unwelcome, unwanted sexual violations of women that happen all too often across the nation. Indeed, Gloeckner adds significant fuel to Moore’s case that graphic images of male nudity are concealed in mainstream culture to maintain patriarchal jurisdiction. It is about ensuring a system that supports the notion that looking signifies control and objectification centers primarily on women’s bodies, not men’s, even in cases where a clear misuse of this inherent power occurs.

While Gloeckner is well aware of the unjust stigma that ideologically discourages her illustrations of male genitalia, this knowledge does not prevent her from critiquing the implicit discrepancies involved in such an unbalanced edict. Gloeckner adds significant fuel to Moore’s case that graphic images of male nudity are concealed in mainstream culture to maintain patriarchal jurisdiction. It’s about ensuring a power structure that supports the notion that looking signifies control and objectification centers primarily on women’s bodies, not men’s.

To be sure, she offers a compelling counterpart to Duchamp’s sculptural artwork of a suggestively positioned, nude woman by presenting a naked male in uncensored detail. But it’s crucial to clarify that the author/artist doesn’t substitute a salaciously posed man’s body for Duchamp’s undressed female. Instead, she conveys the sexual threat that this male adult embodies to his young witnesses/victims and, by extension, to the reader. Therefore, the unclothed individual in this panel could represent a reinterpretation of Duchamp’s work, complicating the image with the naked subject’s own perversion at its core. Indeed, it’s possible that Gloeckner’s frame makes an even more pervasive statement about the cultural forces that condone viewing females as sex objects. Despite the reality that the girls are fully dressed and positioned as mere witnesses to this reckless nudity, they could be sexualized nevertheless. After all, a close inspection of this panel reveals that the nude man makes disturbing eye contact with Minnie, potentially implying that his continued, unashamed sexual conduct may be inspired by her presence. Although we can never truly know this individual’s thoughts in the panel’s single instant, the aroused expression on his face as he masturbates might be related to a sexual fantasy about the young girl he seems to watch so intently. To add to the predatory nature of the moment, it’s likely that Pascal has staged his blatant sexual activity due to the presence of the broken bathroom window. The fact that there is no expectation of privacy demonstrates that Minnie’s stepfather wanted to be seen.

In addition to Gloeckner’s troubling suggestion of Pascal’s intent, I think she’s aware of viewer positionality, particularly concerning gender, in her reinterpretation of Duchamp’s installation. This reality is evident by the way Gloeckner combines subtle threads of distance and identification to create a complex fabric that manipulates our reaction to the controversial figure central to this noteworthy panel. In fact, the girls and the viewer are uniquely positioned in an intimate way so as to relate to this molester during a supposedly private moment, acknowledging what appears to be his objectified stance akin to Duchamp’s piece. In fact, Gloeckner requires us to reconfigure our perception of what we see to comprehend its true meaning. Still, while this personal knowledge matters, verifying the parental betrayal these girls must withstand, there’s more to this awareness than mere authentication alone.

Hillary Chute states the readers’ witness status facilitates testimony, providing a forum in which to memorialize a conveniently marginalized brutality. Chute explains: “We recognize the sensationalism of the event for the child; if we feel implicated in becoming ourselves voyeurs then that does not yet obviate understanding the structures of injustice: instead, it points up exactly how widespread the injustice is, how endemic and culturally threaded” (Chute 79). Chute examines the act of looking from a vastly different angle than Duchamp, who appears to regard it in a much more nefarious light. Unlike the sculptor’s implied perspective, Chute combines a voyeuristic approach with witness testimony to disclose troubling societal malpractice. Therefore, Gloeckner’s ability to transform her readers into engaged spectators exposes more than just her personal pain. It unmasks a suppressed cultural issue that deserves our attention, further underscoring why we should care so deeply about Minnie.

By pointing out how Gloeckner involves readers in Minnie’s trauma, Chute breaks away from theory to stress the need for greater humanity. Therefore, Minnie and her sister are much more than illustrations on a page. They are real victims and the visual culture that normalizes the naked display of women’s bodies has played a central role in their suffering. Moreover, the very society that naturalizes sexualized depictions, beginning with the fine arts, generated Pascal and his attitude that Minnie is nothing more than an object. Additionally, it could be said that Gloeckner blends art history into her personal narrative to underline the foundation of the male gaze and its dehumanizing effect. In the process of calling attention to the structural components that allow for men like Pascal to objectify his stepchildren, Gloeckner reconstructs what it means to look. Her complex criticism of the hypocrisy that permits a woman’s body to be exhibited without allowing for equivalent male nudity contributes to her conception of a feminist gaze. In the end, Gloeckner highlights the consequences of both reducing girls and women to instruments for male pleasure and condoning predatorial behaviors that perpetuate a patriarchal hierarchy with no end in sight.

When A Child’s Life is looked at as a whole, the integration of Duchamp and the illustrative allusions to Western art are not haphazard references. They are unified pieces that demonstrate a pervasive cultural logic behind an abuse that’s much larger than Gloeckner herself and originates from a space beyond her control. Although as an adult Gloeckner has the power to make choices, picking intimate partners at will, she’s still shaped by patriarchal forces that demeaned her in a marginalized domestic space, where her suffering was not acknowledged either inside or outside of her home. To make sense out of this dehumanization, the incorporation of artistic conventions, which might be considered the foundation of today’s visual culture, helps explain Gloeckner’s personal struggle to achieve awareness and create change. From a structural standpoint, her experiences are not unique, but the direct outgrowths of systemic oppression, demonstrating the reduction of women into objects as socially natural. Indeed, Gloeckner summons the ideological tradition of representing images of women in full nudity to illuminate the silent custom of diminishing all of womanhood as objects designed for masculine pleasure. But the process of exposing this devastating patriarchal framework, an effort that Gloeckner undertakes with courageous grace, offers the hope that womanhood can one day overcome the detrimental effects of the male gaze with the presence of a powerful feminist revision.