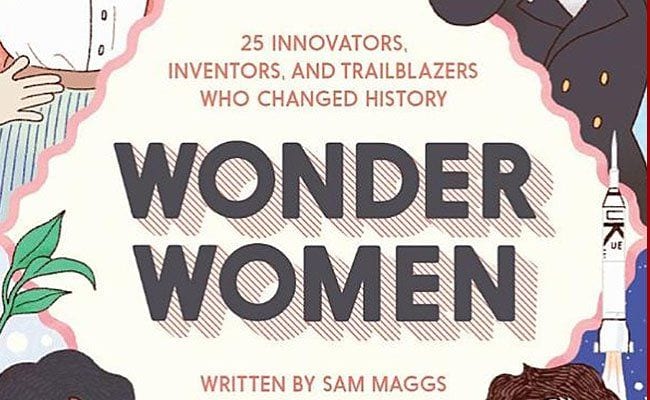

The back cover of Wonder Women: 25 Innovators, Inventors, and Trailblazers who Changed History signals that this book is going to be a little bit different and is going to be a little different in the best possible way. The back of this book doesn’t have a teaser or summary of the book, praise from a famous author, or even the traditional author bio and photo.

Instead, the back of Wonder Women just has a list — a list of things women can do. And what can women do? According to author Sam Maggs, pretty much anything — they can climb mountains, fly airplanes, cure illnesses, and write code.

Inside this little gem of a book are the stories of 25 women who did these things and a lot more.

Maggs divides the book into five sections: Women of Science, Women of Medicine, Women of Espionage, Women of Innovation, and Women of Adventure. While the focus is definitely STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) leaning, Maggs does reference other types of history makers — particularly writers. For example, the first woman Maggs writes about is Wang Zhenyi, a Chinese astronomer, mathematician, and poet. Zhenyi was born in 1768 and “paying no regard to the danger that she could be chopped to bits for her pursuits, or that she would have been deemed unmarriageable (the horror!), she published her opinions anyway and became one of the best-known scientists and poets of her time.”

Some of the women might have been “known”, as Zhenyi was, while they were alive. Then the history books forgot them. Other women never even had the chance to have history forget them — they were charged with crimes, they were ostracized, or their ideas, as Maggs relates, were stolen. Alice Ball, an American chemist and medical researcher, found a treatment for Hanson’s disease (leprosy) in 1916 but died before she could publish her findings. Her research saved numerous lives and was used to treat leprosy until the ’40s. The process, however, was named the Dean Method, after Dr. Alford Dean, the man who took credit for (read stole) Ball’s idea.

Maggs (primarily) looks at women who have either been forgotten or who were never well known, to begin with. Only a couple of names in the book (Ada Lovelace or Elizabeth Blackwell, for example) might be familiar to anyone other than the most diehard history buff. And this is sad, because these are women who earned patents, cured diseases, climbed mountains, and broke down barriers in universities and medical schools. Their actions changed (and are still changing) the way we live today.

Despite their many accomplishments, these women’s stories aren’t always particularly happy, and Maggs doesn’t sugarcoat their lives. Some had horrible childhoods. Some, Maggs relates, died very young or in heart-wrenching ways; allied spy Noor Inayat Khan was shot in the head by Nazis at a concentration camp. Anandibai Joshi graduated from medical school in March 1886 and died of tuberculosis in January 1887.

Still, the book isn’t sad. It’s a celebration. Whether Maggs is talking about a partying spy (Elvira Chaudoir) or “the raddest rocket scientist of them all” (Mary Sherman Morgan), she just makes you want to cheer, and there’s such a wonderful sense of optimism in this book. One woman Maggs talks about in the Women of Medicine section is Jacqueline Felice De Almania, a 14th century Italian physician. As you can imagine, a lot of male physicians weren’t happy about female doctors in the 1300s. They took her to court on the charge of illegal doctoring — and they won. They made it illegal for her to practice medicine and threatened her with excommunication.

This certainly isn’t a happily ever after ending, but consider the way Maggs closes this chapter: “We don’t know what became of Jacqueline after her trial, but I’d like to imagine that she spent her days in a nice warm country healing ladies ‘til she dropped. And that, from the afterlife, she forces the judge who condemned her to watch every graduation ceremony of women medical students ever.”

Maggs not only celebrates these women and their accomplishments; she also encourages others to follow in the footsteps of these wonder women. Each section ends with a Q and A with a modern day/living wonder woman, and these interviews provide advice and guidance for women interested in STEM-related fields. One of the women interviewed, Lindsay Moran, an author, journalist, and former CIA operative, offers this advice to women wanting to break into espionage: “Wear sensible shoes! No seriously, I’d say go for it. The CIA might be a good ol’ boy network, but in my opinion HUMINT (human intelligence) is largely a woman’s world.” Maggs ends the book with an appendix titled “How to Become a Woman of Wonder” and lists online resources, programs, and organizations that can help “ladies of all ages looking to expand their horizons in science, technology, and beyond”.

Maggs’ book is important for another reason as well; it’s a well-written, engaging book that makes history cool and exciting. History should be exciting. It’s full of drama and intrigue and fascinating people. There are heroes and villains, triumph and tragedy. History should be everyone’s favorite subject, and if more people approached it (and wrote about it) like Maggs does, perhaps it would be.