March 1976. Bob Dylan is singing “Sign Language” with Eric Clapton at Shangri-La Studios in Malibu. Yvonne Elliman walks into the control room. For the past month, she’s been recording background vocals for Clapton’s No Reason to Cry (1976). Dylan points to the young singer, cueing his approval. “Eric … she’s good.”

Elliman still marvels at the memory. “That remains one of the high points of my life because he didn’t have to say that,” she says. “It meant so much. I loved his poetry and I loved his songs. You have to love Dylan’s style because nobody else sounds like him. To know that I was amongst those voices is a small accolade that I can carry with me for the rest of my life.”

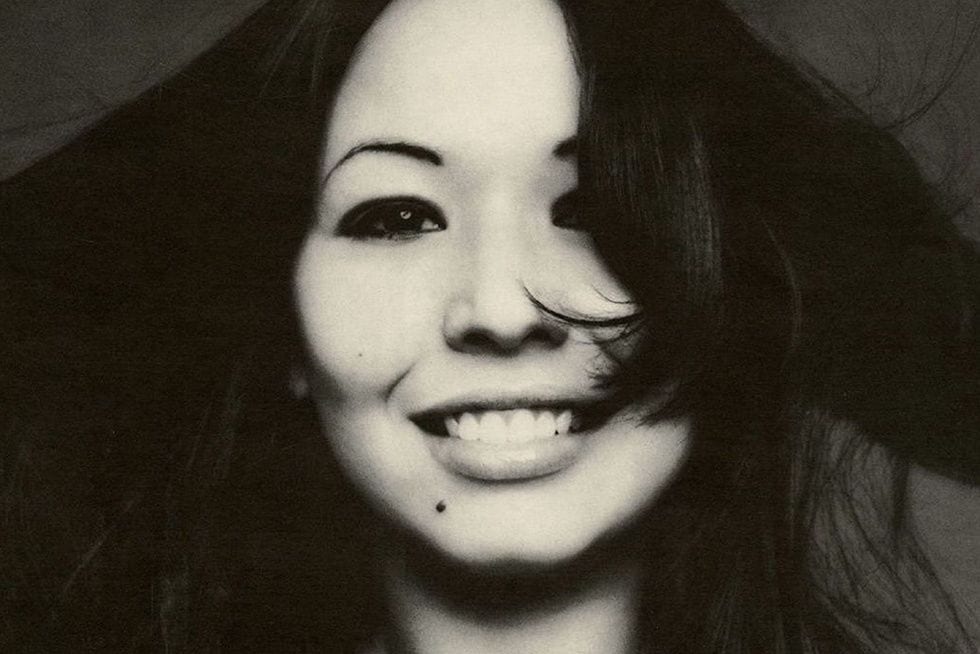

Fifty years since she first left Honolulu for London in 1969, Yvonne Elliman has won more than a few accolades. Broadway critics, rock icons, and disco pioneers alike are intimately acquainted with each inflection of her voice. She’s recorded with everyone from Dr. John to the London Symphony Orchestra and covered the Who and the Bee Gees with equal authority. As a solo artist, she’s fueled both a groundbreaking rock opera (Jesus Christ Superstar) and a cultural phenomenon (Saturday Night Fever). Most recently, her original rendition of “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” even graced Alfonso Cuarón’s Oscar-winning film Roma (2018).

The six solo albums Elliman released between 1972 and 1979 feature a fascinating array of musical personalities — theatre ingénue, rock ‘n roll vixen, soulful torch singer, disco chanteuse, pop balladeer. She mastered each role but never defined herself by any one of them. To this day, Elliman’s chameleonic style is the hallmark of her live performances, whether reprising Jesus Christ Superstar in Italy or singing her biggest hits atop the Ultimate Disco Cruise in Cozumel.

Most impressive of all, Elliman has survived five decades of fashion and fads without losing her flair for singing and songwriting. Legendary artist manager Shep Gordon notes, “The big difference between Yvonne and most of the artists I dealt with was she didn’t have a neurotic drive to be somebody other than who she was. If her career was good one day, great, and if it was just okay the next day, that was okay too. It was more about being Yvonne. She’s got so much Aloha Spirit in her.”

In this exclusive interview with PopMatters, Elliman reflects on both the creative triumphs and personal challenges that brought her from Hawaii to the world stage and back again, while two dozen artists, composers, producers, and industry legends join PopMatters in applauding the singer’s remarkable 50-year career.

Aloha, London

“Barefoot walking on sunshine days, cool waters and blue-green bays,” Elliman once sang on “Hawaii”, a self-penned valentine to her homeland. “I had the best childhood,” she says. “The ’50s in Hawaii — can you imagine? It was just an idyllic place. It was the most beautiful time in my life.”

The singer’s early years mirrored the landscape’s natural tranquility. “I never heard my parents argue, ever,” she says. “I’m an only child. I had all their love. My father was into language. He made me read O. Henry to him when I was seven or eight years old. Once I would read a word, he would make me use it in a sentence and use it all week long.” Elliman’s father also cultivated his daughter’s innate musical talent, taking her to piano lessons and buying her a guitar and ukulele.

However, Elliman’s private study with a vocal instructor at the University of Hawaii ended rather abruptly when he asked her to sing “O mio babbino caro”. Her musical allegiances were not in the curriculum. “I wanted to be Grace Slick,” she says. “I thought she had the most amazing voice. I tried to emulate her with that machine gun-like vibrato.” Undeterred, Elliman sang and played guitar in a quartet called We Folk. Her father managed the group as they became a popular draw, performing at local hotels and military bases, and winning contests all across Hawaii.

One of Elliman’s teachers noticed her talent and recorded her in the studio. “This English guy taught world history and band,” she says. “I played cello. He said, ‘I’m going to go to England for Easter vacation. I’ll bring your tape and play it for some people.’ When he came back he said, ‘There’s this agent who says Just make sure she graduates and we’ll make her a star.‘ I was not a student. I did not go to high school my whole senior year. The teachers got together and decided to pass me because I was a failing student. My father took the money that he and my mother had saved for my college and sent me to England.”

London 1969 seemed like a world apart from the life Elliman had enjoyed in Hawaii. “I suddenly had to wear shoes, man!” she says. “I remember walking down the streets of Soho barefoot because that was my way. It was freezing cold. This old geezer came up to me and said, ‘Darling, you better put on some shoes or you’ll get syphilis!’ I was just desperately homesick so I wrote ‘Hawaii’. That’s the first song I wrote when I got there.

“I sang every moment of the day. I was a great Cream fan. I’d sit in my little flat and play Blind Faith and Led Zeppelin. I was trying to learn the licks. I used to go down to Piccadilly Circus. I’d bring my bearskin rug and my guitar and just sing. I remember the hippies coming around. They’d say, ‘Where’s your hat? You’re not making any money.’ I put the hat down and all of a sudden the shillings are going ching ching ching!”

Elliman landed a regular gig at a club called the Pheasantry. Accompanying herself on guitar, she tested out her favorite Blind Faith song, “Can’t Find My Way Home”, still a mainstay of her set 50 years later. “It was a mysterious-sounding song,” she says. “I don’t know what it is about the song, but it drew me in.” Elliman rounded out her repertoire with songs like “Where Have All the Flowers Gone”, “Up Up and Away”, “To Sir, With Love”, and other tunes she’d performed in We Folk.

One night during the spring of 1970, a young composer named Andrew Lloyd Webber visited the Pheasantry to see Jon Hendricks of jazz trio Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. The vocalist was being considered for the role of Pontius Pilate in Jesus Christ Superstar, an opera that Lloyd Webber had written with lyricist Tim Rice. “Jon Hendricks didn’t show up,” Elliman recalls. “The owner of the club said, ‘Yvonne, you’ve got to do everything you know. Go on!’ On a normal night, I’d only get ten minutes between the acts. This time I got to do everything I knew, so I was thrilled. It was about 40 minutes worth of stuff.” Those 40 minutes would change Elliman’s life.

Tim Rice was summoned to the Pheasantry during Elliman’s performance. “I was at home,” he says. “Andrew rang me up and said, ‘Come on round to the club.’ I went and we heard this exotic Hawaiian-Japanese girl who was terrific … and that was Yvonne. We were just getting together Jesus Christ Superstar to record and needed someone to sing Mary Magdalene. We’d tried one or two people who hadn’t worked out. Yvonne had a beautiful, pure voice. She didn’t quite sound like anybody else.”

Andrew Lloyd Webber made a beeline for Elliman after her set. “I remember this mad man came up to me with completely wild hair,” she continues. “‘You’re my Mary Magdalene!‘ he said. He was talking a mile a minute! He explained that Jesus Christ Superstar was an opera. There were no spoken lines. They were just telling the story of Jesus’ life before he was resurrected, from what they could tell in the Bible.

“My dad was not a practicing Christian and my mother was not a practicing Buddhist, so I didn’t grow up with religion. I just knew the nativity scene at Christmas. I thought Mary Magdalene was Mary the Mother. That’s the only Mary I knew. Andrew had me go to his flat, probably two days later. I heard ‘I Don’t Know How to Love Him’. I thought, That’s a weird song for a mother to sing to her son. I told him that and he said, ‘Don’t you know? She’s not the mother. She’s the whore!'” [laughs]

Murray Head had already recorded the opera’s title theme, which briefly dented the Hot 100 in February 1970, and now it was Elliman’s turn behind the microphone. In June 1970, at just 18 years old, the singer stepped inside Olympic Studios and gave the performance of a lifetime. Elliman sang “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” in one take.

“I was just so lucky to be able to play that role,” she says. “I remember when I performed at an army-navy base in Hawaii, one of the guys said to me, ‘You have the most beautiful cry in your voice.’ When I sang that song, I may have utilized the cry a little bit. I didn’t force it out, but I think I realized that it was part of my voice.” Long before any other singer ever attempted “I Don’t Know How to Love Him”, whether Helen Reddy’s early cover version or Sara Bareilles’ 2018 rendition, Elliman originated the song’s sense of longing and wonder with a timeless interpretation.

Elliman also brought a sensitivity to her lead vocals on “Everything’s Alright”, a scene where Mary Magdalene tries to quell a heated exchange between Judas (Murray Head) and Jesus (Ian Gillan). “Yvonne did it brilliantly,” says Rice, who notes how the trio’s vocal parts were recorded separately. “I don’t recall them singing together in the studio. Everybody was very keen to do it, but they were all working. Ian was with Deep Purple, Murray was acting, and Yvonne had a few things to do. We didn’t do the vocals chronologically or even scene-by-scene, necessarily. We would get someone like Murray in for a day maybe and we’d get as much of his stuff as we could. I suspect we got them together for a promotional photo to promote the album. That was towards the end of the session. In every case, those three people all sang their bits pretty well.”

The singer could scarcely predict the impact that the original Jesus Christ Superstar (1970) concept album would have. “I had a manager,” she says. “She was the one who got me the gig. We were really hungry. We were stealing cocoa from the cocoa machine and mixing it with hot water. That was our meal. When I was offered 100 pounds or a royalty — half of one percent — we took the 100 pounds. They laid five 20-pound notes on the desk. They’re huge! We thought we’d made out like bandits. We went out and got a big case of Mateus wine and steaks. We invited some friends over and had a party on the roof.” [laughs]

MCA/Decca packaged Jesus Christ Superstar as a lavish two-LP set. “MCA did a wonderful promotional job,” says Rice. “They were able to get a lot of attention on individual tracks, but mainly on the entire album. In those days, American radio was pretty progressive. A lot of stations decided that they would play the whole album in its entirety and make an event out of it. Of course, looking back on it, the idea of the title and everything was something that people wanted to know about. The public loved it and it went off like a bullet.” Released in North America during October 1970, Jesus Christ Superstar even propelled Murray Head’s “Superstar” back onto the Hot 100 for 24 weeks where it reached number fourteen.

Peter Brown, who presided as Executive Director of the Beatles’ Apple Corps at the time, was among the industry figureheads watching Superstar‘s phenomenal success. “Jesus Christ Superstar worked instantly,” he says. “As soon as that happened, the Broadway hierarchy thought This is going to be wonderful. Tim and Andrew’s team were approached by many people on Broadway to get the rights to it.” Brown was also friends with London-based manager / producer / music entrepreneur Robert Stigwood, who sought to acquire the theatrical and film rights to Superstar.

“Robert Stigwood was looking to expand his company, particularly in the United States,” Brown continues. “He realized, being the clever guy that he is, that he couldn’t compete with all of these famous, successful people on Broadway, so he came up with the idea in his head that he should get to know Andrew and Tim and go directly to them about management. If he signed them into management, he would then control the rights to Jesus Christ Superstar. He was meeting with Andrew and Tim in New York because they were in New York to promote the album. I happened to be in New York on business for the Beatles because I was still running their company. He was already having negotiations with me about leaving the Beatles’ Apple company to run the Stigwood company in the United States. He didn’t know the American market very well, but of course I did because of my Beatles experience.

“Robert knew I was in town. He invited me to come over in the late-afternoon to the house that he was renting in New York. The purpose of this, it turned out, was that Andrew and Tim were going to be there having a meeting when I arrived. He was going to introduce me to them and, presumably, they would be very impressed that he was on good terms with Peter Brown, who was running Apple! [laughs] I went there and I met them. Robert continued on his plan and bought out their then-management. He kept them to run it on a day-to-day basis. Andrew and Tim were now clients of the Stigwood Organization. Therefore, he could do what he wanted with Jesus Christ Superstar. That was the whole point. By the end of the year, I had more or less finished negotiating my contract to come to America and run the Stigwood Organization in the United States.”

Shortly after Brown’s arrival in February 1971, Jesus Christ Superstar landed at number one on the Billboard 200 the week ending 20 February 1971. “Suddenly there was a hit score without a show!” says Rice. “It snowballed and turned into this amazing thing,” adds Elliman. The album would return to the top for two weeks later that May. Rolling Stone singled out Elliman’s performance, writing “She gives her all on the two sumptuous melodies she has and achieves an erotic intensity and fragility that’s really convincing” (4 March 1971). A month later, “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” debuted on the Hot 100 where it would peak at #28 and give Elliman her first solo hit.

As president of the Robert Stigwood Organization, Peter Brown helped the company chart Superstar‘s course to Broadway by staging a multi-city tour of the show. “Robert and I, being out of the rock ‘n roll era, engaged William Morris Agency and told them we wanted them to quickly put together with us a concert version of Superstar,” he says. “We would do it like we did the rock ‘n roll shows, so you had a full-time cast, full-time orchestra, full-time lighting, and full-time sound. You would move around the country with this whole group like you did with big pop stars. By the time we were ready to launch this, Yvonne was cast and then we cast other people to do the rest, but she was always the key person there to play Mary Magdalene. Tim and Andrew were dedicated to her.

“Before we got the concert together, we were trying to track illegal performances of Superstar. All kinds of illegal productions were popping up all over the United States because it had become enormously successful. Schools and churches and various religious groups thought We love this and we want to perform it. They just copied the album. One of them, I think, was in Missouri. Our lawyers said they thought I should go as the head of the organization to deal with this in the court. I did and I’m now in the witness box, saying these people cannot do this production. It’s owned by our company and by the authors. They cannot do it without permission. The judge said to me, ‘This is my church … you think I’m going to tell them they can’t do it?’ That’s when we decided there was no way we were going to win on that level because the damage would be done before we made any major progress.”

On 12 July 1971, a record-breaking 13,640 spectators attended Jesus Christ Superstar‘s premiere at the Civic Arena in Pittsburgh. “There were thousands of people out there,” says Elliman, who shared the stage with Jeff Fenholt (Jesus) and Carl Anderson (Judas). “They’ve all got their hands lifted up towards me with bouquets. I couldn’t understand it. I was amazed by it all. Then they asked me to come to the hospital and sit by a girl who’d been run over by a car. They wanted me to touch her. I did and she pulled through. They said I was the reason she pulled through. That was heavy. That’s not because of me. I’ll sing the song, but please don’t have me come and bless your child. I didn’t agree to do that anymore.”

Jesus Christ Superstar continued to sell upwards of two million copies while the touring company grossed more than $3.5 million in its first three months. Brown recalls, “The reaction to doing the concert tour in America had become such a big thing that William Morris Agency came to us and said, ‘We need to do a second concert tour. There’s so much demand we can’t deal with one company’, so we had a second one started.”

Broadway soon beckoned. “I was taken off the concert tour and I was given this cherry opportunity to audition,” Elliman recalls. “I was really a fish out of water because I had no experience pounding the sidewalks.” Without any theater credits to her name, Elliman brought Mary Magdalene to Broadway, joining Fenholt, Ben Vereen (Judas), and Barry Dennen (Pontius Pilate) as the show’s principal leads.

One million dollars’ worth of advance tickets, including six weeks of sold-out seats, greeted Jesus Christ Superstar when it opened at the Mark Hellinger Theatre in New York on 12 October 1971. “Jesus Christ Superstar is so stunningly effective a theatrical experience that I am still finding it difficult to compose my thoughts about it,” Douglas Watt exclaimed in his review for the Daily News. “It is, in short, a triumph … ‘I Don’t Know How to Love Him’ was exquisitely sung” (13 October 1971).

Initially, not every cast member welcomed Elliman as warmly as audiences and critics. “All the girls kind of ostracized me,” she says. “Of course, Denise Delapenha had been pounding the sidewalks for years. She got the understudy role. Backstage, I was alone in my dressing room. That’s when Ben Vereen kind of helped me along.

“One night, I thought, I’m going to give Denise a chance to do the role. I called in sick. I put a cloak on and I went to the theater. I got in and went to the side. I was watching the show. When they said, ‘The role of Mary Magdalene will not be played by Yvonne Elliman tonight’, I heard a loud, audible groan from the audience and thought, Oh my God! I have a responsibility. They’re expecting me. Denise got to play the role … and the audience loved her. I became part of the gang because I gave Denise that chance.”

Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice gave Elliman another moment to shine by writing “Could We Start Again, Please?” expressly for the show. “It’s a nice song, actually,” says Rice. “She does it really well. We wanted to give Yvonne, i.e. Mary or whoever was playing the part, something to do in the second half. She has a couple of lines in ‘Peter’s Denial’. Otherwise, she’s just not really in the second half at all.” Like a painter with a blank canvas, Elliman created a world of emotion in each syllable she sang, bringing a delicate urgency to the opening line “I’ve been living to see you”.

Only two years before, Elliman had been busking in Piccadilly Circus and now she was the toast of Manhattan. “It was the best time,” she says. “I remember walking down Broadway in my clogs. I was 19, feeling like I was on top of the world.” Even the frequent sight of protestors outside the theater couldn’t clip Elliman’s wings. “After the show, we’d go to this place and we’d have our pink ladies,” she continues. “There’d always be these people crowding around the front, saying that Jesus was not the way. I thought, Will the real God please stand up? Ben Vereen helped me with that. He’d read the Bible to me. He’d try and teach me because I really had no idea.”

A completely different project that spotlighted Elliman arrived in record shops during Superstar‘s ascent on Broadway. Composed by Deep Purple member Jon Lord and performed with the London Symphony Orchestra, Gemini Suite (1971) featured a series of six movements written for “amplified instruments and orchestra”. Elliman and Tony Ashton sang solos for the “Vocals” sequence. In reviewing Gemini Suite for UNC-Chapel Hill’s college newspaper, one writer asked, “When is a record company going to wise up and put Yvonne Elliman on an album?” (26 January 1972).

It was a timely question with a short answer — now. Throughout January and February 1972, Elliman recorded her full-length solo debut for MCA/Decca at Phil Ramone’s A&R Studios in New York. Yvonne Elliman (1972) showcased the singer’s facility with a range of material, including one of her own tunes (“Interlude for Johnny”), plus her previously recorded showstopper from Jesus Christ Superstar.

Though Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice would be credited as producers, Rice clarifies that he actually produced the album with Bill Oakes. “I don’t know why Andrew wasn’t involved in it at all,” he says. At the time, Oakes was Peter Brown’s personal assistant. He’d worked at Apple’s London office and relocated to New York when Brown became president of the Robert Stigwood Organization. “Bill had been the gopher kind of person at Apple,” Elliman recalls. “I was in the studio once when Paul McCartney was recording. I walked in and he started to sing ‘I Don’t Know How to Love Him’.” [laughs] Oakes took an active role in Elliman’s first album and suggested several of the songs, including tunes by Dave Mason and Stephen Stills.

Fresh from playing on McCartney’s Ram (1971), plus albums by Labelle, B.B. King, Herbie Mann, and Don McLean’s American Pie (1971), prolific New York session guitarist David Spinozza arranged Elliman’s maiden release. “I was coming off all of these hit records in New York that I’d played on,” he says. “I had my finger on the pulse. People found out that I could arrange for strings and horns — I wasn’t just a guitarist. At the time, you had to hire musicians and someone had to tell them what to play. I was kind of sought-after, even though I was young myself, because they knew I could do that. I knew every studio musician. Yvonne’s album was the first session that I was the leader of, so I got the musicians and wrote the charts for all of the arrangements.”

Spinozza corralled some of the city’s finest players like Hugh McCracken (guitar), Kenny Ascher (organ/piano), Stu Woods (bass), Rick Marotta (drums), and Ralph MacDonald (percussion). “I remember negotiating with Robert Stigwood so they’d get double scale,” he says. “Nobody was getting double scale yet, except maybe guys like Eric Gale and Richard Tee. I said, ‘I can get these guys but you have to pay them double scale. They’re not going to work for scale. We’ve already played on hit records. We’re making $60 and the records are making millions. These guys are going to contribute not just what I write on the paper but they’re going to come up with stuff that’s going to help make these songs sound good.'”

With the band in place, Elliman visited Spinozza at his apartment on 71st Street to begin shaping the songs. “I was living with my wife and my young daughter,” he says. “I had a little upright piano. Yvonne came by and we worked on the songs. She sang great.” Elliman slowly began peeling herself away from Mary Magdalene through a batch of offbeat, contemporary tunes by South African writer John Kongos (“I Would Have Had a Good Time”), Gilbert O’Sullivan (“Nothing Rhymed”), and former Asylum Choir member Marc Benno (“Speak Your Mind”).

The album also included one of Spinozza’s original songs, “Everyday of My Life”. He continues, “Yvonne either asked me, ‘Do you write songs?’ or ‘Do you have a song?’ I played it for her and she liked it. I think it was as simple as that. I wasn’t really trying to sell her the song. It just came out of me because I was actually going through stuff about my life and being a studio guy.

“‘Everyday of My Life’ was kind of a mixture of two things. When you’re young, you try to get your whole life into one song. [laughs] I don’t write like that today! I was only three years older than Yvonne and I was married with a child. I was really struggling with not wanting to be a husband. I wanted to be free. ‘What’s bad for me is good for you’ — we were just disagreeing on everything. Then as I got to the chorus, I started writing about what it was to be a studio musician, all of the changes also meaning the chord changes. The ‘rearranging’ had to do with rearranging my life but also I was always arranging songs. I was getting called as a session musician so I was making money. I wasn’t having any money issues, but I was definitely having why-am-I married issues. Yvonne did a great job with it.”

Polydor’s edition of the album, titled I Don’t Know How to Love Him for the UK market, also included a new song Lloyd Webber and Rice had penned for single release, “What a Line to Go Out On”. “Andrew and I did a deal with Polydor in the UK to do some singles,” Rice explains. “They were rather keen to get another version of Superstar, but they ended up getting a lot of weird singles!” [laughs]

MCA/Decca prepared Yvonne Elliman for release in the spring of 1972. Trade papers eagerly championed the album, with Cashbox and Record World deeming her version of “Can’t Find My Way Home” a “pick of the week”. “I love the way she sings that,” Spinozza exclaims, echoing Rice’s own assessment of the track. “Elliman sings with a depth beyond her age,” wrote the Arizona Republic (7 May 1972) in its review of the album while the St. Louis Post-Dispatch noted, “Yvonne does her best in the Judy Collins mold in her own ‘Interlude for Johnny’, a soft lyrical ballad with the mystery of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Suzanne'” (12 May 1972).

Industry plaudits didn’t correlate to record sales, however. “It’s a nice album, but it wasn’t a hit of any size, which was a pity,” says Rice. “There were quite a lot of sessions and taking quite a bit of care about it. I think MCA didn’t really push the boat out for it. I’m not blaming them because it probably wasn’t a commercial enough album. Everybody who wanted ‘I Don’t Know How to Love Him’ had it on the Superstar album anyway.”

Elliman certainly had her own expectations for the album. “You know what? I thought it was going to be huge because Superstar was so famous,” she says. “By this point, I was getting lucky in so many ways that I thought, Everybody’s going to love this! Of course, I don’t think it sold twelve albums. I really had no idea about the record business.”

The one thing Elliman knew — unequivocally — was she’d grown weary of playing Mary Magdalene night after night on Broadway.

“Jeff Fenholt and I went to do the Phil Donahue Show in Chicago,” she continues. “Phil said to me, ‘How are you enjoying being on Broadway?’ I said, ‘Well actually, I’m kind of bored.’ [laughs] I was being totally honest. One night, I changed the blocking because I wanted to do it a different way. The stage manager said afterwards, ‘Yvonne, you can’t do your own blocking. You have to stick with the format.’ I learned that lesson — you don’t change the blocking on Broadway or you lose the spotlight and you don’t get seen!”

Superstar also exacted a personal toll on the singer. “People started calling me Mary,” she says. “I was losing sight of myself. I didn’t want to be known for musicals because it really wasn’t exactly my trip. I had so much to do yet. After six months, I was out of there.” In April 1972, Elliman announced her departure from the Broadway production.

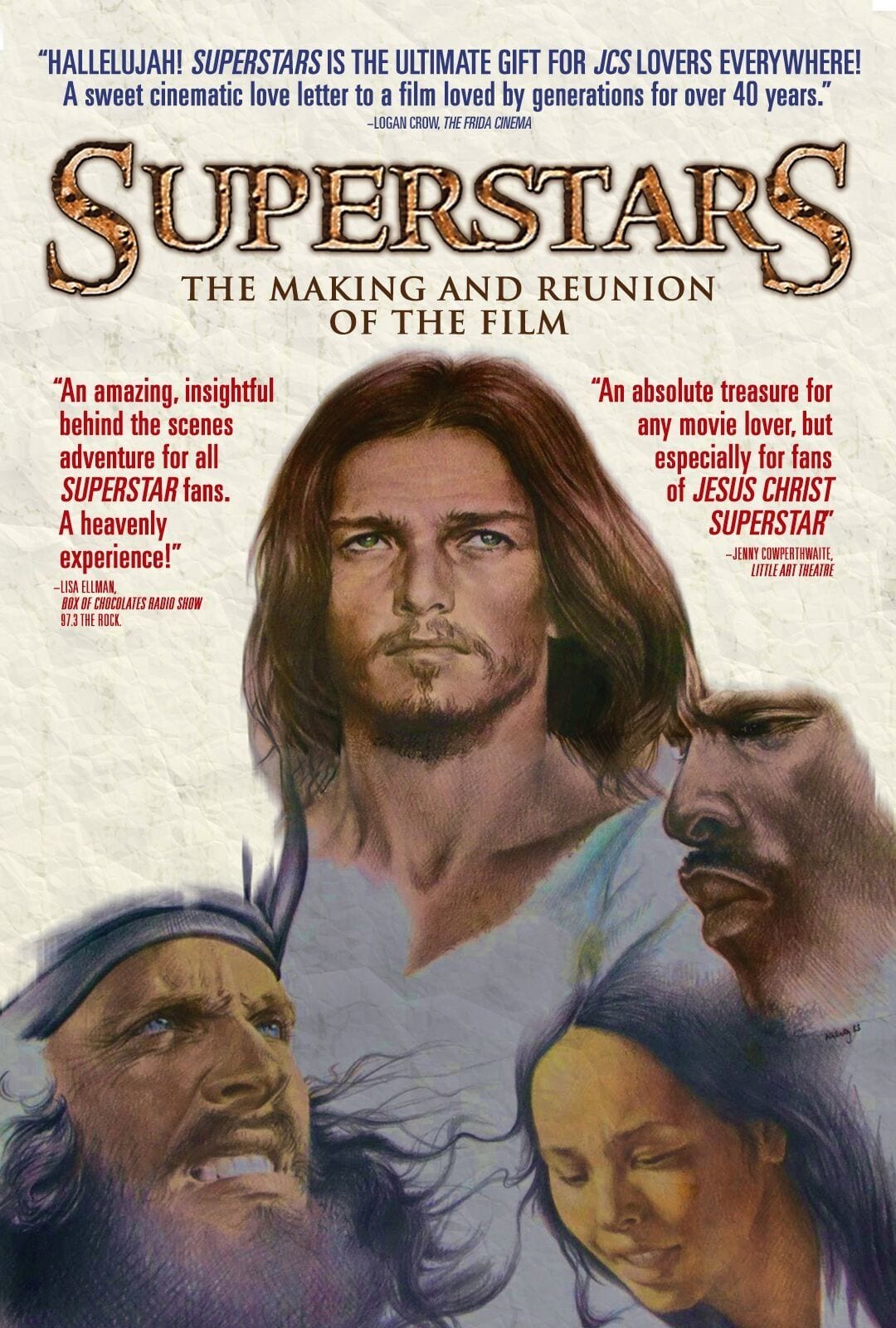

The hiatus from Mary Magdalene didn’t last long. Oscar-nominated director Norman Jewison cast Elliman for Stigwood’s film version of Jesus Christ Superstar (1973). The singer spent the fall of 1972 on location in Israel with Ted Neeley (Jesus) and Carl Anderson (Judas), who’d both understudied on Broadway after starring in different touring companies of the show. Elliman and Barry Dennen now held the distinction as the only actors who sang in all three major incarnations of Superstar — the concept album, the Broadway production, and the film version.

In translating the musical to film, Jewison created one majestic sequence after another. He placed Elliman on a hilltop overlooking the desert during “Could We Start Again, Please?” “I love that song,” she says. “Norman Jewison had me go to the far point of the desert. They walked me out there. They started the track and I started gesticulating wildly. I thought they couldn’t see me because I was so far away. He said, ‘Cut!’ He came walking up to me — and it’s a long walk — and said [quietly], ‘Darling, I’m real close.’ He squared my face. ‘The camera’s right on you. You don’t have to move your hands everywhere.’ I learned a lot about zoom at that point!” [laughs]

Jewison’s lens captured Elliman and her cast mates in resplendent form. Carl Anderson tore into his role with a mighty ferocity during numbers like “Heaven on Their Minds”. “What a singer!” says Elliman. “The singer of all singers. As far as doing the role, there was nothing he couldn’t do. He was amazing. Carl did it beautifully.” His performance of “Superstar”, in particular, radiated magnetizing star quality.

Similarly, Ted Neeley created the definitive interpretation of the title character. “He brought everything to it,” says Elliman. “When we were on Broadway, Jeff Fenholt was sick one night and Ted had to do the role. He brought the house down because you believed everything he was saying. He shook with anger and rage. He loved with such a tenderness in his eyes. Tim and Andrew weren’t always 100% for him doing the movie, but I think in the end, after they saw the screen test, there was no other choice.”

When Jesus Christ Superstar opened the following August, critics noted how Jewison and his actors only enhanced the material. Roger Ebert called the film “a bright and sometimes breathtaking retelling of the rock opera of the same name” (15 August 1973). Elliman herself received rave reviews for her onscreen work, with the New York Post exclaiming “Yvonne Elliman’s Mary Magdalene packs an emotional wallop” (17 August 1973) and the Daily News writing “Yvonne Elliman sings the role of Mary Magdalene with touching simplicity, her face beautifully expressive” (9 August 1973).

“The film stands up quite well,” says Tim Rice. “I’m a great fan of Norman Jewison. I think it was a very hard thing to do in the sense that the album and the show had only recently come out. I’m very pleased it was made, especially by such a distinguished director.” Peter Brown agrees, adding, “We wanted to do it quickly. I don’t know whether we did it too quickly, but I think Norman Jewison did a very good job.” The Hollywood Foreign Press Association duly honored Jesus Christ Superstar with several Golden Globe nominations, including “Best Motion Picture — Musical or Comedy”, while Elliman, Neeley, and Anderson each scored nominations for their captivating performances in the film.

Farewell, Mary Magdalene … Hello Eric Clapton!

Elliman shifted into a different musical mode upon her return to New York. Between 15 January – 5 February 1973, she appeared with Stan Getz at the Rainbow Grill, performing a number of bossa nova songs that Getz had recorded with Astrud Gilberto, João Gilberto, and Antonio Carlos Jobim a decade earlier. “The woman who was my manager in London was a good friend of Stan’s,” she says. “‘The Girl from Ipanema’ was one of the songs I used to do. I’d learned the guitar part when I was in Hawaii with my folk band. I sang that for Stan somehow. He said, ‘Would you like to do a couple of weeks with me?’

“It was amazing. I remember singing a Mose Allison song. I was with Jack DeJohnette, Dave Holland … these jazz greats. People in the jazz world today know these guys. I had no idea. I wasn’t a jazz singer. I didn’t follow jazz. I was staying at Stan’s house. After the gig every night, he would drive me back in his car. He would tell me all of these incredible jazz stories about who he hung out with and all of these incredible people he worked with through the years. I didn’t realize how lucky I was.”

Billboard applauded Elliman’s residency with Getz, noting how her vocal talents shone in a jazz context. “She moves confidently through several styles and forms and is that rare thing — a singer who can work intelligently and relate to accomplishment from a jazz artist,” the magazine wrote. “She is a poised young singer” (10 February 1973). However, Elliman was about to take a sharp turn from bossa nova back to rock.

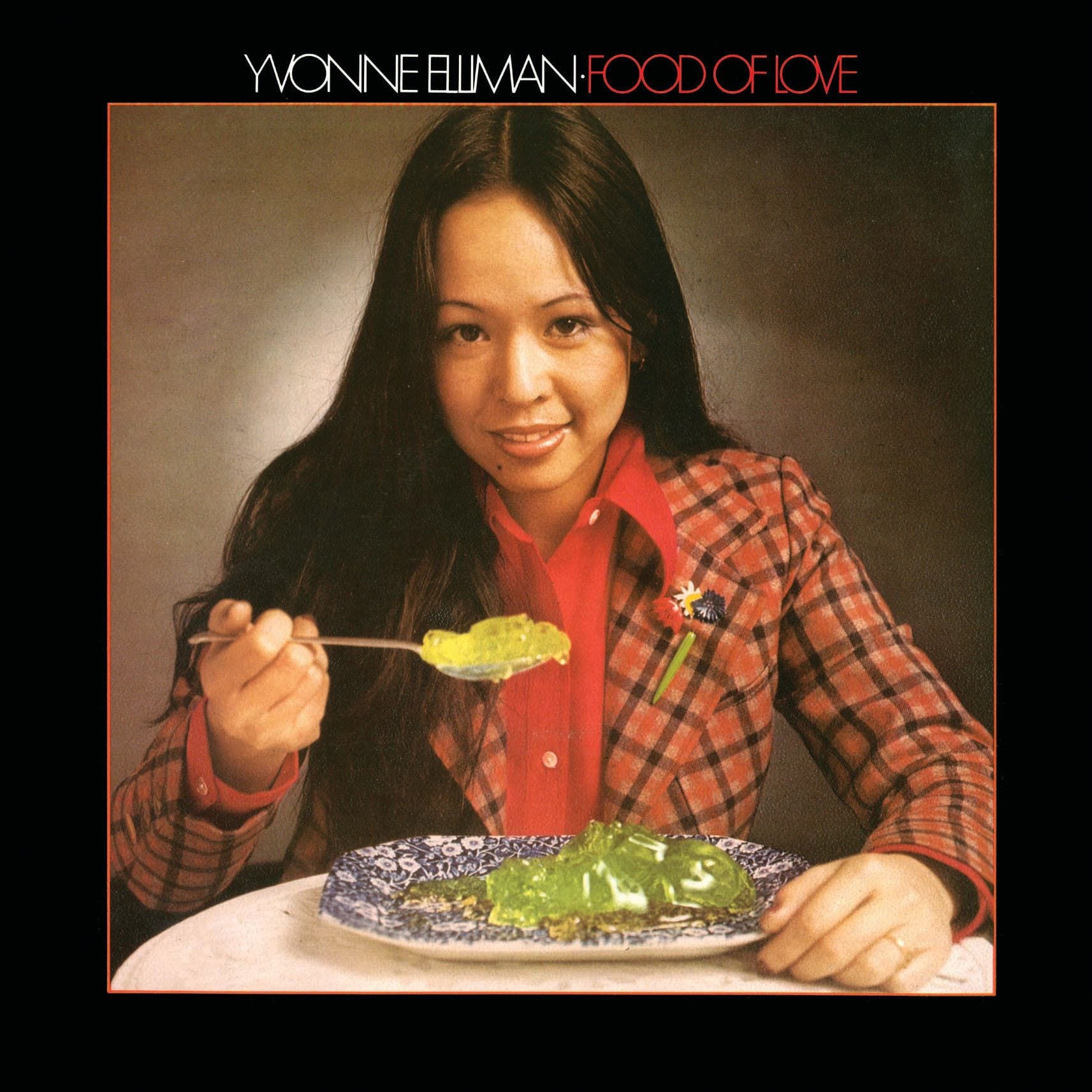

London-based Purple Records, which had released Jon Lord’s Gemini Suite via EMI, bankrolled Elliman’s next full-length album Food of Love (1973). Purple recording artist Rupert Hine had just released two albums for the label, Pick Up a Bone (1971), recorded with his writing partner David MacIver, and Unfinished Picture (1973). “At the time, Purple was putting money into what they considered were strong artistic endeavors,” says Hine. “That was quite a rare thing, really.” For Elliman’s first and only Purple release, MacIver-Hine would pen some of the most compelling material she’d ever sing.

Elliman had a specific mandate for the songwriters — banish her Mary Magdalene image. “Rupert and David said, ‘We’ll write anything you want to sing about’, so I thought of every nasty thing I could think of,” she recalls. “I said, ‘I want to sing about gluttony!’ so they wrote ‘Casserole Me Over’.” Hine continues, “Yvonne just loved the idea of sexual connections with food. She had these fantasies about rolling around in food, in a sort of medieval feast or Roman orgy kind of way. We held no reserve there in making that lyric sort of fruity, pardon the pun!”

Elliman boldly explored same-gender love in Robbie Robertson’s “The Moon Struck One” and another MacIver-Hine original, “Muesli Dreams”. She explains, “I felt that was just the opposite of what Mary Magdalene was about, not that it’s a bad thing, but back then, it was naughty to be a lesbian. I wanted to sin as much as I could.” As she gently cooed lyrics like Your breasts against my eyes can never be wrong, Elliman turned sin into a beguiling, Sapphic daydream.

Initially, Purple considered other producers for Food of Love until Elliman intervened. Hine recalls, “I lived in a central London flat, which I shared with David. He had one floor and I had the other floor. Yvonne would come over. We’d have songwriting sessions where we’d play the beginning of a song just to see whether that was something that felt right for her. We’d get a feeling for the right keys. We were well advanced on all the songs before Yvonne suddenly asked out of the blue, ‘Couldn’t you produce this?’ I said, ‘I’m not a producer.’ She said, ‘Yes, you are. It says right here on your last album, your Unfinished Picture album.’

“Of course that was a challenge that I was up for. In a way, I took a leaf out of Roger Glover’s production of my first album (Pick Up a Bone) as a key to how to produce Yvonne’s album, rather than my much more idiosyncratic and experimental second album. I knew I wanted really good orchestral arrangements for some of the tracks to be played by really great musicians, where I could take the appropriate seat as a proper producer and not be playing everything. I was the junior kid in those sessions. Retrospectively, I am surprised that I had the confidence to go about doing an album of that complexity at that time. It was my first album as a record producer.”

Conductor Martyn Ford led his orchestra with equal parts finesse and precision, especially on Ann O’Dell’s exquisite arrangement of “More Than One, Less Than Five”, a song that Hine had previously released on Pick Up a Bone. “It is the only MacIver-Hine song on Food of Love that already existed,” he says. “We wrote the other songs off the back of these long conversations with Yvonne. It was a following wind that we should include ‘More Than One’ from the get-go. David and I always liked it a lot. I also think that the Purple guys, John Coletta and Tony Edwards, loved that song too. Yvonne heard it as she was recapping our body of work. She spotted that song and just loved it. David thought it would work particularly well with a woman’s interpretation. It was a beautiful version.” Indeed, Elliman’s haunting vocal forged an intimacy between herself and the listener that seemed suspended in time.

Hine expanded Elliman’s “Hawaii” to widescreen proportions, framed by Simon Jeffes’ (the Penguin Café Orchestra) sumptuous arrangement. “‘Hawaii’ was lovely,” says Hine. “Yvonne had talent as a writer. We were always encouraging her to write more. She always figured that other people wrote so much better, but that was probably part of the process of working with a huge machine like Andrew Lloyd Webber, Tim Rice, and their whole world. I’m not blaming them, but when there’s musicals, you end up singing some pretty classically written songs that aren’t necessarily going to be part of your own writing as an artist. You come up with different things, although to some extent ‘Hawaii’ did still reflect a classical piece of songwriting.”

Four years after first writing “Hawaii” in London, Elliman added another verse that referenced the commercialization of Hawaii. “The reason that last verse is in there is because Bill Oakes (my first husband) said, ‘You’ve got to make something about the fact that Hawaii’s changed so much.’ He actually wrote the lyrics to that last verse. I did get some criticism from the locals who said, ‘Hey how come you said that about Hawaii? That’s not how it is.’ I did agree with Bill because Hawaii had become this touristy kind of place … but the locals know where to go!”

Elsewhere, Hine’s production of Jim Steinman’s “Happy Ending” unveiled a masterpiece. Diaphanous musical textures shrouded Elliman’s plaintive performance. “That song’s got an amazing melodic sensibility,” says Elliman. “The chord changes really take you somewhere. Rupert got a great sound out of my voice. There wasn’t a lot of distortion, which is kind of hard with a voice like mine because it’s breathy.” Elliman also earned the distinction as the first artist to record a song by Steinman, who’d later achieve massive success as the composer behind Meat Loaf’s Bat Out of Hell (1977) and epic pop hits like Bonnie Tyler’s “Total Eclipse of the Heart” (1983).

A combustible cover of the Who’s “I Can’t Explain” brought Food of Love to a fever pitch. “That was one of my favorite songs when I was a teenager,” Elliman says. “Rupert called Pete Townshend and asked if he would come in and play on it.” Hine continues, “I knew that Pete had this flat around the corner from where we recording at A.I.R. Studios. I hadn’t met him. Somebody gave me his number. I called him completely cold. He picked up. I said I was in the middle of doing an album with this lady who’d been Mary Magdalene in Jesus Christ Superstar, that she’s breaking away from all of that and wants to be sort of raunchy and rocky. She’d love to do a version of ‘I Can’t Explain’. Could we entice you up to the studio to play guitar?

“He didn’t seem to really miss much of a beat. He said, ‘Where are you recording?’ I said, ‘A.I.R.’ He said, ‘When?’ I said, ‘Anytime you like, mate. Just pop down.’ I think it was literally two or three days later that he turned up with his own amp. When we did that album no one had touched ‘I Can’t Explain’ since the Who’s single, so I think he quite liked the idea of giving it another thrash.

“I took three guitar takes. Rather than choosing any best bits — they were all really good — I just played all three back together. It was so much more energetic, biting, aggressive, and punchy than the original, which had been recorded some ten years before — a long time in studio recording evolution. It was a huge success for all of us, including Pete. Pete loved it.” In fact, “I Can’t Explain” reached the Top 40 of Billboard‘s Alternative Songs chart 25 years later when Fatboy Slim sampled Townshend’s riff on “Going Out of My Head”.

“I Can’t Explain” quenched Elliman’s thirst for something “meaty, beaty, big, and bouncy”, to borrow one of the Who’s compilation titles. “It was brilliant,” says Hine. “Yvonne was absolutely fantastic on that. The backup singers were all of incredible quality as well, which gave the record the kind of bite that really went with the guitar. They weren’t session singers. They were Doris Troy, Rosetta Hightower, and Joanne Williams … big soul singers of that time in England.”

In certain respects, Food of Love offered a more satisfying portrait of Yvonne Elliman than her debut. The Los Angeles Times called the album “a well-done showcase …promising a fine future” (11 November 1973). Billboard was even more effusive. “This is a frighteningly good LP,” the magazine wrote. “She expresses herself with a magnitude which clearly shows her great capability. She is an outstanding singer who can grasp you with tenderness or wail right along the dynamics of a fiery rock arrangement” (25 August 1973). Despite the reviews, neither Purple Records nor MCA Records (Elliman’s label home in the U.S.) could generate sales or chart action.

“I love that album,” says Elliman. “Rupert and Dave were beyond the times. It was a really interesting recording that got lost. I don’t know what happened.” At the time, the singer was managed by Purple Star, a company formed in tandem with other Deep Purple business lines. “They didn’t know what to do with me,” she continues. “They wanted to change my name to ‘Kim Shane’ because they thought ‘Yvonne Elliman’ was too ethnic. It didn’t work.”

In the meantime, Elliman enjoyed married life with Bill Oakes. The two had wed a year earlier in June 1972. Oakes had since been promoted to president of Stigwood’s RSO label, home to Eric Clapton and the Bee Gees. “Eric came out of hibernation and went to record at Criteria Studios in Florida,” Elliman recalls. “Robert Stigwood said to Bill, ‘Would you go down to Florida and make sure Eric’s okay?’ Bill said, ‘Would you like to come?’ I said, ‘Are you kidding? Of course!’ I brought my twelve-string and six-string guitars and went down there.” Unbeknownst to the singer, she’d become an integral part of Clapton’s long-awaited solo return, 461 Ocean Boulevard (1974).

Produced by Tom Dowd, the album found a newly focused Clapton. Elliman continues, “They were doing ‘I Shot the Sheriff’. Eric pointed at me and said, ‘You sing, don’t you?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I sing a little bit.’ I went in there and put down the high harmony. He loved my voice and how it blended.” Elliman lent her voice to several tunes, from “Willie and the Hand Jive” to the crystalline harmonies on “Please Be With Me”. Clapton even used her twelve-string on “Let It Grow”.

Elliman and Clapton also joined forces on “Get Ready”, a new song they wrote together during the sessions. “Eric had written the first part of it,” Elliman recalls. “It was just a song that he was kind of playing around with in the studio. He said, ‘Do you have any lyrics that you might want to put on a verse?’ I had lyrics for another song that I’d written: I never needed a run around, dizzy hound / checkin’ out the bitches in heat. You’ve got a lot of nerve, dishing out what you serve / waggling your piece of meat.

“I tried it out and they all cracked up. He wrote the bridge and I wrote the second part of the bridge right there in the studio.” The duo’s playful duet would not go unnoticed. In his review of 461 Ocean Boulevard, Village Voice critic Robert Christgau highlighted “Get Ready’ as one of the album’s strengths, noting that Clapton’s voice “takes on a mellow, seductive intimacy he’s never come close to before” (1974).

Elliman returned to New York newly energized from the Criteria sessions. She continues, “I was over the moon: ‘Fucking hell! I got to be on an Eric Clapton album. Wait till I tell my friends.'” She was also part of a hit album: 461 Ocean Boulevard became one of 1974’s top releases, spending four weeks at number one in August and September while “I Shot the Sheriff” crowned the Hot 100 for one week.

461 Ocean Boulevard began Elliman’s three-and-a-half year adventure with Clapton. “Eric’s manager calls me up out of the blue and says, ‘Eric wants to say something to you.’ Eric got on the phone. He said, ‘Would you like to be in my band?’ ‘Yes!’ ‘Okay, bye.’ He made the arrangements and we all met in Barbados for the rehearsals. To be suddenly invited into Clapton’s band … can you imagine? I was the first female to be in his band and the first female to ever share a stage with him. I had that credibility. Plus I had a name of my own. I thought, Man, this is it. If I don’t go anywhere else, this is fine with me.

“When I joined the band, I asked Eric if I could do ‘Can’t Find My Way Home’. He said, ‘Oh yeah, I need a smoke break.’ When I would do the song, I’d get such huge applause from the audience. Eric started to notice that it was a song that everybody loved. He then joined me onstage and started singing harmony with me and playing guitar.”

Elliman’s own solo career was at a crossroads. Aside from MCA’s promo single for “Come on Back Where You Belong” — the theme to The Midnight Man (1974) starring Burt Lancaster — she hadn’t released any new material since Food of Love. In a sense, she was gaining more traction as a background vocalist for Clapton. According to Robert Stigwood, RSO’s red cow logo symbolized good health and good fortune. The enterprising impresario was about to bring Elliman some good fortune of her own.

RSO Rising

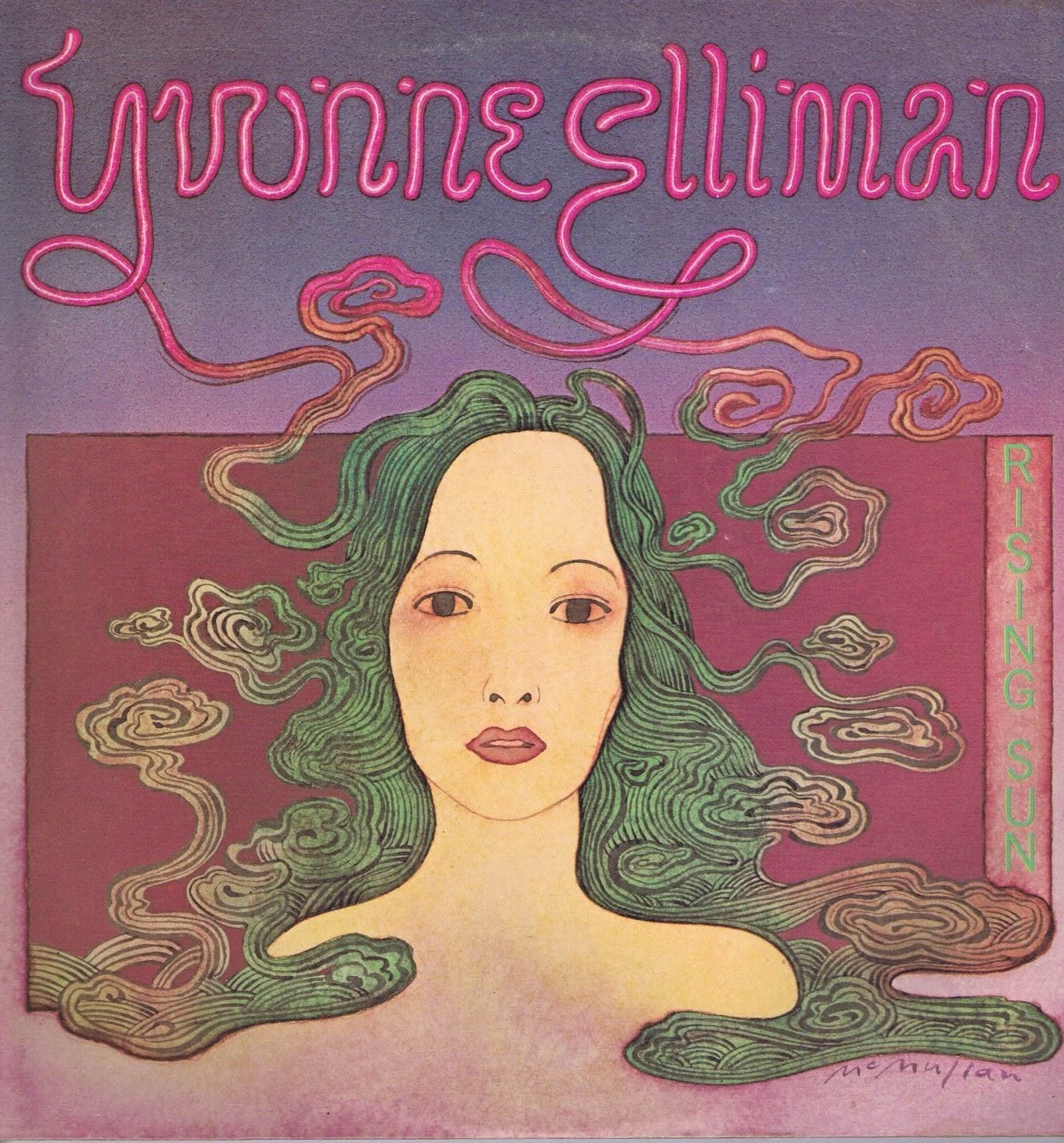

Yvonne Elliman officially joined RSO’s roster as a solo artist in 1975. Legendary Booker T. and the M.G.’s co-founder/guitarist and former Stax Records songwriter / producer Steve Cropper was selected to produce the singer’s debut for the label, Rising Sun (1975). Dividing sessions between Memphis and Los Angeles, Cropper outfitted Elliman with first-rate material, including songs by the Eagles (“Best of My Love”) and Todd Rundgren (“Sweeter Memories”), plus an early recording of Richard Kerr and Will Jennings’ pop standard “Somewhere in the Night” and a new version of Paul Cotton’s “Bad Weather”, which Cropper had produced for Poco four years earlier.

Originally demoed by Kim Carnes, “From the Inside” typified Cropper’s soulful approach to pop. “I loved it when I heard it,” says Elliman. “It was commercial within the realm of being hip enough.” Songwriter Artie Wayne’s lyrics blossomed with Elliman’s heartfelt interpretation and a soaring string arrangement by Larry Muhoberac. A cadre of musical virtuosos rounded out the rhythm section, including alumni from the Bar-Kays and Booker T. & the M.G.’s.

Famed keyboardist Marvell Thomas (son of Rufus Thomas) lent a special touch to Elliman’s own “Who’s Gonna Save the World”, a song inspired by W. Eugene Smith’s heart-wrenching photographs that documented victims of Minamata disease in Japan. “All the fish that they were eating had all this poison in it,” Elliman says. “The babies were born completely deformed. I remember crying on the airplane looking at this picture in LIFE Magazine of this Japanese woman holding this very deformed baby. That’s when the song came.”

“Steady As You Go” gave a sobering glimpse of Elliman’s own reality. “It was about the drunken life,” she says. “I was in Clapton’s band. I was trying to keep up with the boys and fit into the rock ‘n’ roll mode. I even had an English accent. That’s not how I grew up, but I wanted to fit in. I remember being absolutely hungover one morning, sick as a dog. I thought, This life of overindulgence is not good. I was just really fed up with the debauchery.

“I remember I was sitting at a hotel, looking at everybody pack up the gear. I’d had a rough night the night before. I was sitting there with my whiskey bottle. Pete Townshend walked by me. He said, ‘Darling, you shouldn’t drink that. You’re a very pretty lady. You shouldn’t do that to yourself.’ I stopped drinking for two weeks, which is really hard to do when you’re on the road and you’re doing shows every night.”

Throughout 1975, Elliman became one of RSO’s most visible artists. She sang on Clapton’s There’s One in Every Crowd (1975) album and E.C. Was Here (1975) live set. While promoting Rising Sun, she joined the Bee Gees in Chicago for their Soundstage concert, performing “Steady As You Go”, “Can’t Find My Way Home”, and soloing on the Gibb Brothers’ “To Love Somebody”. Best of all, Rolling Stone championed Rising Sun. “She places herself in that rank among the very best women singers of pop,” the magazine stated, selecting “From the Inside”, “Somewhere in the Night”, and “Bad Weather” as the album’s best cuts (17 July 1975).

Yet press reviews and star collaborations were hardly enough to guarantee success. Even RSO’s distributor at the time, Atlantic Records, couldn’t save Rising Sun from meeting the same fate as Elliman’s two MCA releases. Neither the album nor the singles made the charts, essentially bringing the singer back to square one.

While Elliman met Clapton in Malibu for No Reason to Cry (1976), RSO hatched an idea for the singer’s next single. The Bee Gees had resuscitated their career with Main Course (1975), featuring the number one “Jive Talkin'”, and were primed to deliver another blockbuster on their follow-up, Children of the World (1976). In a strategic bit of cross-roster pollination, Robert Stigwood brought Elliman a fetching mid-tempo tune from the album, “Love Me”. “I thought it was a nice pop song,” Elliman says. “The way the Bee Gees did it was very sweeping.”

Motown producer Freddie Perren, who’d recently produced number one hits for the Miracles (“Love Machine”) and Capitol recording act the Sylvers (“Boogie Fever”), had an undeniable Midas touch at the time. He took “Love Me” and recast it with a dreamy R&B groove. “I liked him,” says Elliman. “He made it sound really good. He was an excellent producer. When he had the track ready, I went in the studio. It was fast. I never saw the band!” Elliman effortlessly blended yearning and desire in her vocal, bringing an appealing, dusky tone to the Gibb Brothers’ melody

Just weeks before Elliman joined Clapton on tour in the fall of 1976, “Love Me” bowed on the Hot 100 the week ending 2 October 1976. Exactly two months later, it soared to number five on the Adult Contemporary chart and rewarded Elliman with her biggest pop hit yet, peaking at #14 on Christmas Day 1976. In between, it landed at number six in the UK. It had taken five years since “I Don’t Know How to Love Him”, but Yvonne Elliman was back on the charts.

“Love Me” prompted a far different response from Clapton’s audience, however. Elliman recalls, “Robert Stigwood said to Eric, ‘Do you think you could switch songs from ‘Can’t Find My Way Home’ to ‘Love Me’? He said, ‘Sure that’d be fine.’ He had the band learn it. We played ‘Love Me’ and it was the biggest dud. The audience looked at me like I was some kind of alien. I felt so humiliated. I think I did it twice. It was just so embarrassing. The band was sort of embarrassed too. You cannot mix whatever that genre was with the rock that was happening then. Never the twain shall meet, man.”

At Stigwood’s insistence, Elliman returned to the studio with Perren to complete her second RSO set, Love Me (1977). “Freddie would play me these things and I’d think, Oh my God. He’s going down the road that I don’t want to go down. This real MOR pop stuff,” she says. “I did it because Stigwood said do it. I had a hard time saying no to people because I don’t want to criticize their work. I tended to listen to whatever the producers told me. I wasn’t really the type that knew exactly what I wanted to do.”

A cover of Barbara Lewis’ 1963 hit “Hello Stranger” signaled a step in the right direction. “When Freddie asked me what I wanted to sing, ‘Hello Stranger’ was the first thing that came out of my mouth,” she says. “I’d loved ‘Hello Stranger’ since I was a little kid. He said, ‘Oh God, yeah. I love that song.’ I did it exactly like Barbara Lewis. I kind of copied her inflections because I couldn’t see singing it any other way. Freddie recorded it very much the same way too.” The tune seemed tailor-made for Elliman, whose loving homage exemplified the durability of Lewis’ song.

Whereas the Dells had sung the song’s signature “shoo-bop, shoo-bop’s” on Lewis’ version, Elliman sang all of her own background vocals on “Hello Stranger” and the Love Me album. “Freddie taught me a lot about harmony,” she says. “I love harmonizing because that was my roots with my folk band. When Freddie got a hold of me, he told me to sing the harmony. I did and he said, ‘No that’s wrong. If you sing this note, that’s not in the chord. You sing a harmony within the chord.’ He played the chord. ‘You hear that?’ I said, ‘Man you’re right!'”

Ultimately, half of Love Me featured songs by Perren’s wife Chris Yarian and her writing partner B.J. Verdi. Elliman also contributed “I Know”, a new self-penned tune that featured her on acoustic guitar. “‘I Know’ was written when the end of my marriage was coming,” she says. “I don’t write happy love songs. I’m a little caustic! I had ‘I Know’ done, but I didn’t have the rest of it so Freddie wrote the bridge.” Perren also wrapped the album with a Frederick Night song (“Uphill Peace of Mind”) plus a collaboration between Melissa Manchester, Carole Bayer Sager, and David Wolfert (“Good Sign”).

Given that Elliman’s first three albums missed the charts altogether, Love Me marked a considerable improvement for the singer. RSO issued “Hello Stranger” as a follow-up to the hit title track. The song topped the Adult Contemporary chart in April 1977 and peaked at #15 on the Hot 100 a month later. Elliman wasn’t the only artist profiting from the song’s success. “Barbara Lewis called me up and thanked me,” she says. “Since she wrote it, she was getting the royalties from it.” Remarkably, “I Can’t Get You Outta My Mind” delivered yet another smash hit for Elliman, climbing the Top 20 on both the UK singles chart and the Adult Contemporary chart.

Love Me brought Elliman several honors. In September 1977, the singer won “Best New Female Vocalist” at Don Kirshner’s Third Annual Rock Music Awards. “It’s nice to be acknowledged after knocking around for eight years,” Elliman quipped at the time. “I said that because it was true,” she laughs, recalling the ceremony. “I’d been around for years. Finally, something came along and it was such a great thrill.” By year’s end, Billboard recognized the singer’s watershed year, naming her “Top Easy Listening Singles Artist” behind Barbra Streisand and Barry Manilow and including her in the Top Five “New Pop Albums Female Artists” and “Pop Singles Female Artists” charts.

Though Love Me had boosted Elliman’s industry status, the overall direction of the album confounded critics. “Yvonne Elliman is a first-rate singer … whose style embraces contradiction,” Stephen Holden wrote in his review for Rolling Stone. “She combines the strong projection and straightforward phrasing of a rock singer with a kittenish sweetness associated with Olivia Newton-John pop” (2 June 1977).

“Kittenish sweetness” certainly had its own merits but Elliman herself questioned the softer undertones of her music at the time. “I missed rock because that’s where my head was,” she says. “I loved Santana, the Eagles, Cream, and Led Zeppelin. I was getting very despondent.”

Shep Gordon entered Elliman’s life at just the right time. As a manager, he’d brought both Alice Cooper and Anne Murray to the top, and had recently added Teddy Pendergrass to his roster. His creativity and determination adapted to all genres of music. That combination is exactly what Elliman needed.

“Yvonne had a really unique vocal quality,” says Gordon, recalling what drew him to the singer. “She was a great package. I had just moved to Hawaii. I got friendly with Yvonne’s husband at the time Bill Oakes and I had done some business with Robert Stigwood. Yvonne was very involved in the Stigwood world. She was in that orbit and it was a good orbit to be in at the time.”

Elliman appreciated the focus and attention Gordon brought to her career. “My life changed for the better when I met him because I didn’t know what I was doing anymore,” she says. “He probably thought that I was quite lovely, but that I could be even more lovely if they put a little work into me! [laughs] He actually came to my house one day and he said, ‘Play me some of your songs that you’ve written.’ He listened to some things that I’d done. He wanted to know what I wanted to do. That was so important because everybody else wanted me to do what they thought I should do.”

Meanwhile, CBS broadcast the infamous Rolling Stone 10th Anniversary Special, a two-hour show featuring an oddly eclectic mix of artists from Bette Midler to Billy Preston. Billboard later described the special as “an utter embarrassment to fans of the magazine” (10 December 1977), taking particular exception to a 15-minute Beatles tribute called “A Day in the Decade”. Vignettes included everything from Ted Neeley sitting cross-legged amidst dancing strawberries (“Strawberry Fields Forever”) to Patti LaBelle singing “Polythene Pam” in front of a glittering spider web.

Elliman and Richie Havens provided a respite of calm to the proceedings, singing a duet of “Here Comes the Sun” and “Good Day Sunshine”. “Richie was such a lovely man. Really sweet,” she says. “We lip synched. That was so weird. It was strange because they were really clinical about the whole thing. It seemed a little austere. It didn’t parlay what we were singing about — the sun.” Decades later, A.V. Club would name their duet as the only redeeming quality of the entire sequence.

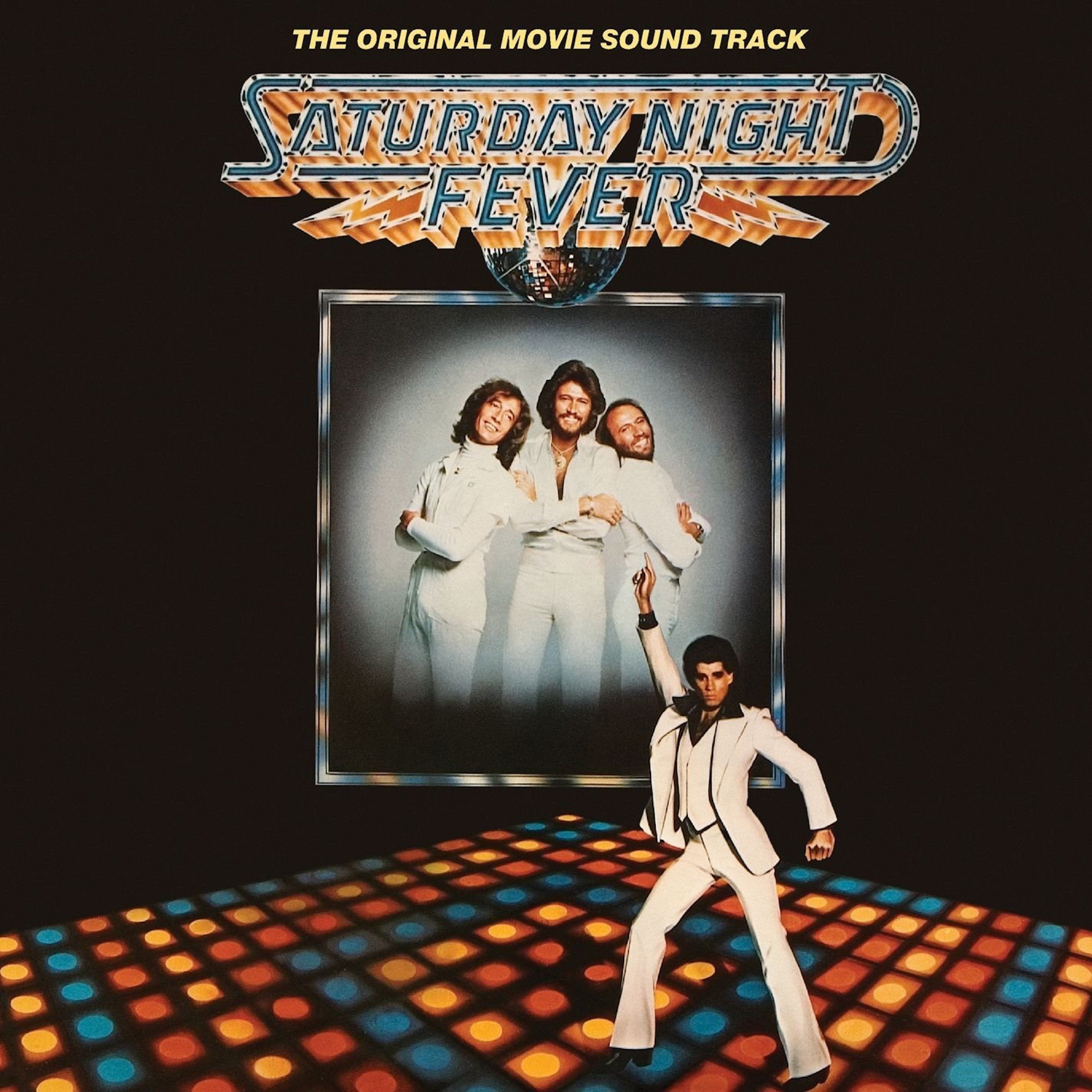

Back at RSO, the company’s profile would go from a simmer to an explosion with Robert Stigwood’s next endeavor. Bill Oakes was supervising the music for Saturday Night Fever (1977), the first of three features that Stigwood produced as a vehicle for John Travolta. “Bill was the one who brought it to Robert’s attention from Nik Cohn’s original article in New York Magazine,” notes Peter Brown about Fever‘s source material. The film would feature five new songs composed by the Bee Gees, one ballad plus four tunes steeped in the contagious hooks and disco-oriented rhythms that characterized their career renaissance on Main Course and Children of the World.

As producer of Fever‘s soundtrack, Oakes played Elliman two of the new Bee Gees songs. “I was offered ‘If I Can’t Have You’ or ‘How Deep Is Your Love’,” she recalls. “When the Bee Gees did ‘If I Can’t Have You’, it had big strings. I thought, Wow! ‘How Deep Is Your Love’ didn’t affect me the same way.” Elliman amplified the desperation in “If I Can’t Have You” with equal parts passion and pathos. “It’s a sad song,” she says. “It’s about somebody who’s ready to end it if they can’t have that person.”

Resuming his successful partnership with Elliman, Freddie Perren turned the Bee Gees tune into a majestic three minutes of torch-inflected disco. James Gadson (drums) and Scott Edwards (bass) cushioned the rhythm as Wade Marcus’ horn and string arrangement swirled atop Perren’s production. Background singers Julia Waters, Maxine Waters, and Marti McCall blended flawlessly, complementing Elliman’s lead vocal with a scintillating timbre. “Their intonation is perfect,” says Elliman. “The high notes in that song are key. Whenever I do rehearsals with anybody, that’s what we work on the most — getting those high notes. Without that, ‘If I Can’t Have You’ wouldn’t be what it is.”

Saturday Night Fever wouldn’t be what it is without “If I Can’t Have You”, either. RSO scheduled the soundtrack’s release a month before the film’s December premiere. The two-LP set debuted at #47 on the Billboard 200 the week ending 26 November 1977, just one spot ahead of another disco opus bowing on the chart as well, Once Upon a Time (1977) by Donna Summer.

Following the film’s star-studded Hollywood screening at Mann’s Chinese Theatre on 7 December, Saturday Night Fever opened nationwide on 16 December 1977. That same day, Yvonne Elliman joined a choir of music and film luminaries on MGM’s backlot where Robert Stigwood filmed the closing scene to one of his next extravaganzas (and notorious flops), Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978). A week later, the Bee Gees’ “How Deep Is Your Love” began a three-week stint at number one, sparking a string of four chart-topping singles from the soundtrack. Fever was infectious.

Night Flight to Number One

Just as Saturday Night Fever arrived in record stores during November 1977, Elliman finished up her third RSO album, Night Flight (1978). RSO paired her with Robert Appère, the former Director of A&R for Elton John’s Rocket Records who’d produced Kiki Dee, Nigel Olsson, former Skylark lead singer Donny Gerrard, Brian and Brenda Russell, plus Neil Sedaka’s number one comeback hit “Laughter in the Rain”. Having worked with Toto and produced albums by the Section (Danny Kortchmar, Leland Sklar, Craig Doerge, and Russ Kunkel), Appère also had a direct line to LA’s most in-demand session players.

The producer met with Elliman and Shep Gordon to discuss her vision for the album. “We tried to do explorative kind of work with Yvonne,” he says. “We tried to find out who she really was and what she liked.” Elliman relished the opportunity to tailor the project closer to rock. “Up until that point, I was really just doing everything everybody wanted me to do and really not showing what my true heart was about,” she says. “Robert was a very good producer for me as far as really asking me what I wanted to do. He was very interested in me being happy with the stuff I was recording. We went through hundreds of songs to choose the right ones.”

Album opener “Baby Don’t Let It Mess Your Mind” had a fascinating trajectory before landing on Night Flight. Appère first co-produced it with Neil Sedaka, who wrote the song with Phil Cody for his Solitaire (1972) album. Three years later, Appère produced two more versions of the song on singles by Donny Gerrard and Ted Neeley (the B-side of “Paradise”), each with its own unique flavor. “I really believed in that record,” he says. “I thought, This is a hit record. Why wouldn’t it be a hit record?“

“I think Donny Gerrard’s version is the version that Robert played for me that got me all hot for the song,” Elliman chuckles. “There’s a lot for a singer to do within that song. I enjoyed singing it. I thought that song was beautifully recorded.” Appère produced his most elaborate version of “Baby Don’t Let It Mess Your Mind” yet. The song’s 30-second intro, replete with softly wailing sax, evoked a vivid, shadowy scene before Elliman even sang a note. Her voice cast a spectral presence over the track.

Danny Kortchmar’s “In a Stranger’s Arms”, previously recorded by the David Sanborn Band and Kortchmar’s own group Attitudes, captured a slice of nightlife beamed from the pages of Looking for Mr. Goodbar. It pulsed with a menacing groove as Elliman warned The dream you’re in, can surely spin, out of control. The song itself spun into a dizzying swirl of sounds, an effective touch to a story that had no clear resolution. “I thought it was a wild kind of record,” says Appère. “Yvonne made it hers in the middle of all that craziness.”

“Up to the Man in You” hailed from Elliman’s own songbook. “It was about the dissolution of the first marriage I was in,” she says. “It was all about, Let’s be honest with each other. It’s up to the man in you to rise to the occasion.” Cecilio & Kapono — the first group from Hawaii to receive a national recording contract (Columbia Records) — added shimmering harmonies to the song. “That meant a lot to me,” Elliman says. “I thought they did a fabulous job.” Appère adds, “They would double and triple their parts perfectly. They were like meticulous machines. Just unbelievable.” Rolling Stone would later highlight the song in its review of the album, noting “‘Up to the Man in You’ shows how far she can go with just syncopated backup vocals and some stinging Lowell George guitar-playing” (18 May 1978).

Cecilio & Kapono also sang backgrounds on “Sailing Ships”, a tune written by Elliman’s friend Stephen Bishop. “I love his music,” she says. “‘Sailing Ships’ was a huge favorite of mine. My mom worked at this bar near Pearl Harbor. A lot of the merchant marines would go in there. She’d tell me the story about how ‘Sailing Ships’ was the song they’d ask to be played on the juke box when they came in. She would hear that so many times a day. It’s a beautiful song. When something brings tears to your eyes, you don’t know why. It’s just an emotional tug.” Imbuing “Sailing Ships” with a wistful tenderness, Elliman brought Bishop’s tune to life as the closing track on Night Flight.

From the heart-wrenching ballad “Down the Backstairs of My Life” to a cover of “Sally Go ‘Round the Roses” (featuring Kiki Dee on backgrounds), Night Flight excelled in its variety. “The songs sound like they’re from different times and different places but I didn’t feel bad about that,” says Appère. “I wasn’t trying to make a record that blended completely with itself. I just wanted to make a record that showed all of the different ways that Yvonne could go, all of the different people that she was.”

To capitalize on the success of Saturday Night Fever, RSO added “If I Can’t Have You” to Elliman’s latest release. Stylistically, the song clearly owed more to Love Me than Night Flight. “If only I’d held on a little bit longer before releasing Love Me, then I think Love Me may have gone gold,” Elliman says. “There were already two hits on it that had done really well. All it needed was that big blaster that would have carried it over the top, but ‘If I Can’t Have You’ didn’t make it in time.”

Of course, millions of listeners had already discovered “If I Can’t Have You” through Saturday Night Fever before Night Flight was completed. Within six weeks of the film’s release, the soundtrack was selling upwards of 500,000 units per day. “RSO was a force,” says Gordon. “It took over the industry for a minute. Saturday Night Fever started the frenzy. It was revolutionary and gigantic.” The soundtrack began its staggering 24-week stint at number one the week ending 21 January 1978. The very next week, “If I Can’t Have You” debuted on the Hot 100.

During an appearance on American Bandstand, Elliman announced her first solo tour. It doubled as an image makeover for the singer. “RSO took away my jeans and put me in red satin pants and chain mail tops,” she says. “Raquel Welch’s husband did my clothes.” Her stage wear was about the only glamorous part of touring. The accoutrements she’d enjoyed in Clapton’s band were but a memory. “Gone were the Lear jets, the yachts, and the fancy train rides,” she says. “I had to ride a bus all across the midwest and play little dives where the guitar player had to sit on the steps that led down to the basement because the stage was too small.”

Elliman made her first tour stop on 13 February with a two-night stand at the Bijou Café in Philadelphia. “Ms. Elliman is at last her own woman,” raved The Philadelphia Inquirer. “The new image is still kind of sweet but there is also a lusty, free-wheeling quality to be considered these days. Most encouraging of all, though, is Ms. Elliman’s treatment of the contemporary ballads she includes in her repertoire. The voice is warm and vulnerable, yet strong enough to do the job that has to be done. She is equally at ease with the hard-edge, sensual rockers” (15 February 1978).

That same week, early reviews of Night Flight surfaced in major outlets. “Night Flight is a fine album. (Yvonne Elliman) has a lovely, smoky soprano. She phrases with conviction in both ballads and uptempo numbers,” wrote The New York Times (17 February 1978). Billboard published its own rave review, describing the set as “a stylistically crafted gem. A delightful listening experience” (18 February 1978). The Star-Gazette later noted how the album served “a refreshing glimpse of the new Elliman — the torch singer” (16 April 1978).

When Night Flight debuted on the Billboard 200 the week ending 11 March 1978, “If I Can’t Have You” was holding fast at #21 during its seventh week on the Hot 100. Fourteen days later, the song joined four other RSO singles in the Top Ten, including Eric Clapton’s “Lay Down Sally” off Slowhand (1977), which featured Elliman on background vocals. In fact, RSO had dominated number one since January as “How Deep Your Love”, “Stayin’ Alive”, and “Night Fever” earned the Bee Gees three consecutive chart-topping singles. In between, RSO artists Player and Andy Gibb also crowed the top with their own non-Fever singles.

“If I Can’t Have You” shuffled around the Top Ten for seven weeks before it finally supplanted the Bee Gees’ “Night Fever” from number one on 13 May 1978. “I was lying in bed,” Elliman recalls. “I remember getting a call from RSO, saying, ‘Guess what Yvonne? You’re number one with a bullet!” Just like that. I got up out of bed. I’m sitting there by myself, trying to feel what I should feel. It was really a tough scramble to get to that top spot. I remember getting in the car and hearing it on the radio. I had to pull over to the side of the road because it was number one. It was a tremendous high.”

Elliman celebrated her first number one single with a party at Shep Gordon’s restaurant, Carlos ‘n’ Charlie’s. Later that evening, she received an offer to guest star on an episode of Hawaii Five-O. “I was acting all of a sudden, which I found out I can’t do,” she laughs. “I watched Hawaii Five-O for the first time in years and I was cringing looking at myself. I’m so uni-dimensional. This forlorn face looking at Jack Lord is the same face with the frown across the top that looked at Jesus. I thought, I got to change this. There’s more to my face than that! I’m a very colorful person when I’m talking to people!”

There were many reasons to smile where Elliman’s music career was concerned. “If I Can’t Have You” went gold and Night Flight peaked at number forty on the Billboard 200, becoming the highest-charting solo album of her career. Strangely, RSO didn’t push another single off the album, though there was no shortage of contenders. “They kind of gave up on it pretty quickly,” she says. Instead, Elliman returned to the studio with Robert Appère to record a brand new single, “Savannah” (1978).

Just a year earlier, Appère had produced Matthew Moore’s Winged Horses (1977) album, which featured Moore’s own version of “Savannah”. He recalls, “Matthew was just a very different kind of person than I’d ever known in my life. He had this unusual voice. His older brother had a similar voice. They were in the Joe Cocker Band. They wrote ‘Space Captain’. He was very musical.” Like “Baby Don’t Let It Mess Your Mind”, Appère sought to give “Savannah” another chance through Elliman’s interpretation. “I just love that record,” he continues. “When I love something, I don’t let go of it easily!”

“I love ‘Savannah’ too,” Elliman continues. “I loved it because Matthew Moore has the most amazing high voice. It’s incredible! He did the backgrounds on it.” Elliman also retained the integrity of Moore’s original by keeping the lyrics intact. “I don’t think I cared that it’s about me running away with a chick,” she says. “I wasn’t concerned about that. There was never a question about ‘Is Yvonne into women?’ even though I’ve had three songs about having a female as a lover!” [laughs]

Elliman premiered the song in June 1978 during Grease Day U.S.A., a television special celebrating the release of John Travolta’s second film with Robert Stigwood, Grease (1978). While viewers might have expected an “If I Can’t Have You”-styled clone, Elliman delivered a sizzling stew of rock and pop. “‘Savannah’ is a favorite song of a few people that I’ve met in my life,” she says. “I’m always amazed by that.” She could count Billboard among the song’s fans. “The hot instrumentation along with the singer’s emotional delivery sets a fiery mood that gains in intensity,” the magazine stated in its review (22 July 1978).

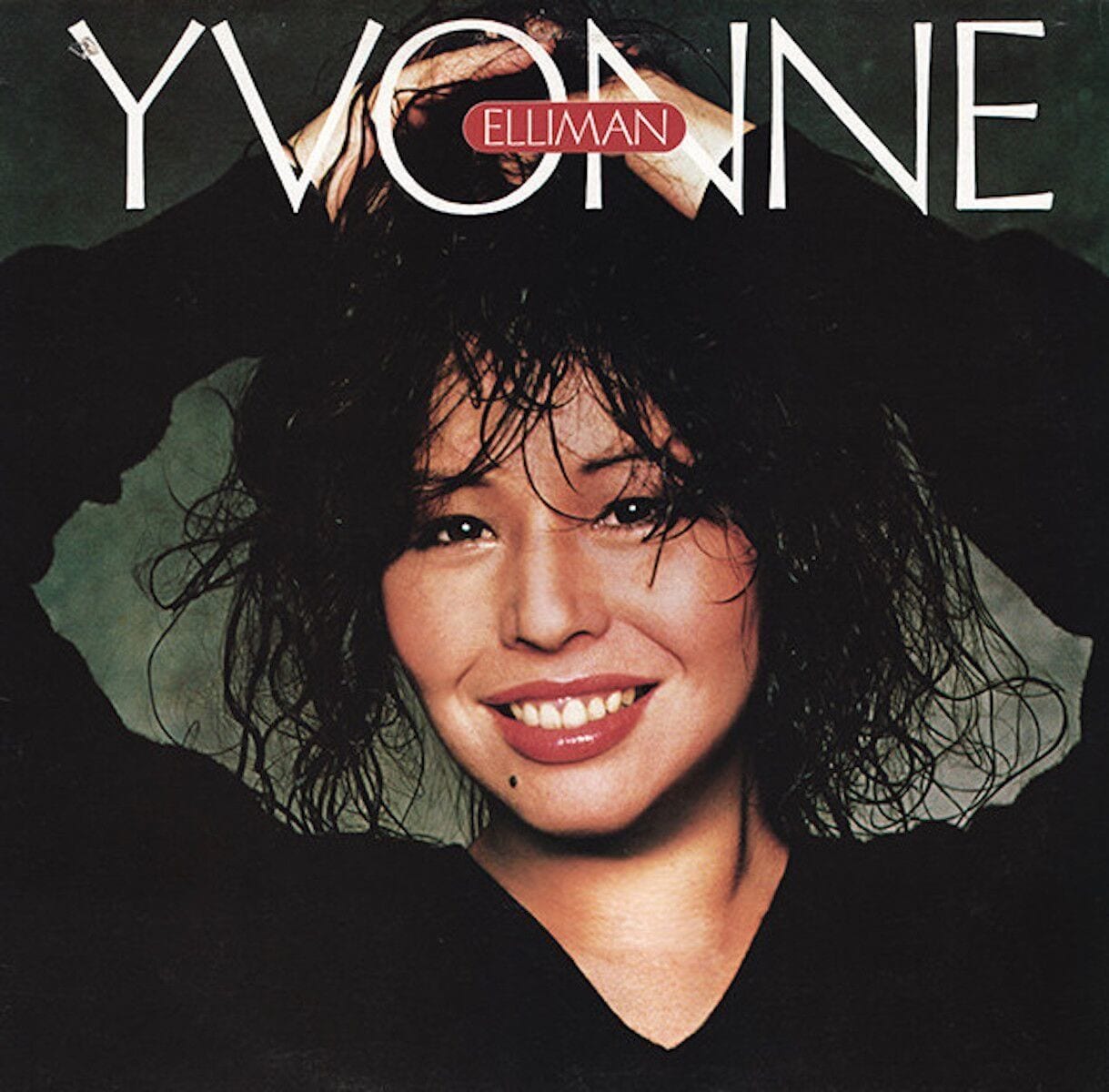

Following the release of “Savannah”, Elliman toured with Leo Sayer and resumed her sessions with Appère for what ultimately became her final RSO album, Yvonne (1979). Tom Snow’s “Cold Wind Across My Heart” was among the more intriguing experiments. Appère took “Cold Wind” a few steps beyond Richard Perry’s own version for the group Night (featuring Chris Thompson). “Robert was exceptional,” says Elliman. “He would spend hours getting the right sounds.” Snow himself played keyboards on the track, embellishing Appère’s gripping and mysterious soundscape.

A medley of two Ray Charles classics, “Hit the Road Jack” and “Sticks and Stones”, turned into a memorable duet with Dr. John. “I think it was (bassist) Paul Stallworth’s idea to record that,” Appère recalls. “I thought, If we’re gonna do this, we might as well do it right. Dr. John happily came down.” Elliman continues, “It was such a big thrill to have somebody of that stature come and play on your album. Dr. John was an icon at that point. I remember seeing him a long time before. He’d close his eyes and there were eyeballs painted on his lids! I loved that about him. When I met him, he was just an ‘ordinary Joe’ kind of person. He just walked in with that kind of gravelly voice. He was a lot of fun.”

Recording Benard Ighner’s “Everything Must Change” challenged Elliman’s stamina, however. “I think Yvonne and I were in Colorado for something and we heard Randy Crawford’s version,” Appère recalls. “I love that song. It brings a tear to your eye.” In fact, “Everything Must Change” nearly brought Elliman to tears. “That one was hard to do,” she says. “I remember trying to go so deep into myself and sing it with everything that I had. We did that many nights, many times over. I was losing my voice, basically, towards the end of it. The heads of RSO came in and listened to all of these different takes to choose which one was best. They picked that last version. To this day, I don’t know if it was the right choice. I sounded like I was on the brink of something really sad in my life.”

Elliman also took a turn with Eric Carmen’s “Nowhere to Hide”, Jimmy Holiday’s “I’m Gonna Use What I Got to Get What I Need”, and an updated version of “Can’t Find My Way Home”. However, the latter tune wouldn’t make the cut. Appère recalls, “I was hoping for a 180-degree departure from the original and didn’t feel that version was much different, although it was a great band and Yvonne’s performance was wonderful.” Appère’s rough mix of “Can’t Find My Way Home” would later appear on PolyGram’s compilation The Best of Yvonne Elliman (1997), serving up Elliman’s customarily strong interpretation of a song that’s lived with her since 1969.

Though RSO would postpone Yvonne for nearly a year, Elliman was thoroughly satisfied with Appère’s work on their second album together. “He got me the most amazing players,” she says. “He had the ‘A’ people in all of Los Angeles. Of course, it ended up costing half a million bucks — everybody was so expensive — but wow, did I have some players! It was just so incredible. I was extremely lucky.”

While RSO juggled Yvonne on the release schedule, Robert Stigwood prepared his third movie with John Travolta, Moment By Moment (1978). Elliman was tasked with recording the title theme to Travolta’s onscreen romance with Lily Tomlin. “I worked my ass off singing that thing,” says Elliman. “First of all, when I saw the movie, I thought, No one’s going to believe that Lily Tomlin and John Travolta are in love. [laughs] It’s not believable. I don’t think the song made it any more so.” Ironically, the single of “Moment By Moment” might have been the most successful aspect of the film, peaking at #59 in January 1979.

The soundtrack to Saturday Night Fever, however, was hotter than ever. It won “Album of the Year” at the 21st Annual Grammy Awards in February 1979 during the middle of its 120-week run on the Billboard 200. Presenting at the 1979 Disco Awards four months later, Elliman was now aligned more closely with disco than rock. “Saturday Night Fever was huge in good ways … and huge in other ways,” says Gordon. “It put Yvonne in the middle of that dance thing for a minute, which she really wasn’t part of. Her challenge was to grow out of that, being an artist rather than a vehicle for a song.”

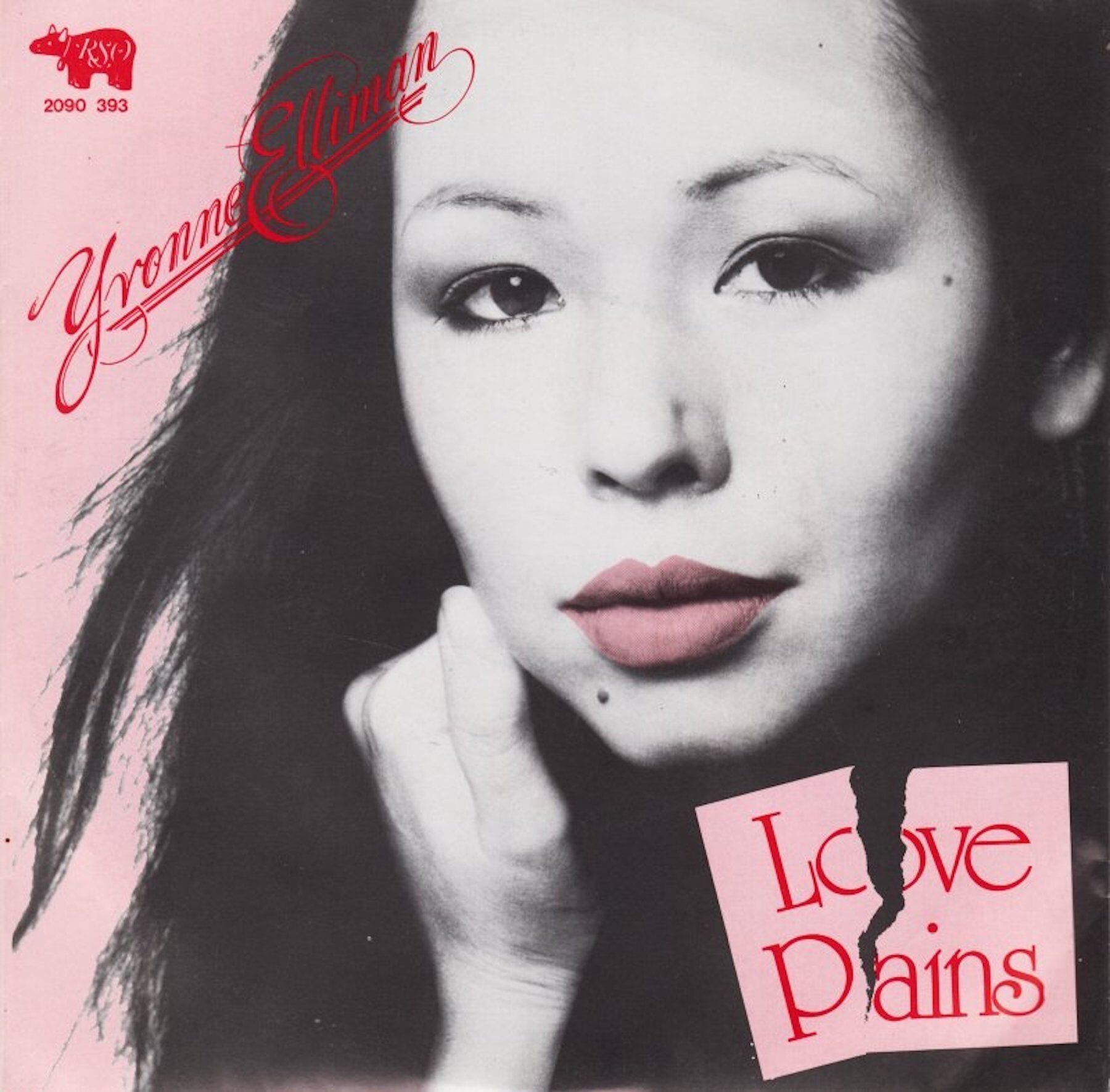

A year after Elliman had begun recording Yvonne with Robert Appère, RSO enlisted producer Steve Barri (Cher, Dionne Warwick, the Four Tops) to cut three tracks with the singer. Written by Barri, Michael Price and Daniel Walsh, “Love Pains” was catnip for disco audiences. As Elliman gamely wrapped her voice around the song’s irresistible melody, the verse and pre-chorus created a tension that begged to be released. “You’re lifted up when you get to the chorus,” she says. “You don’t expect the song to go to those chords at that point. When I hit the chorus of that song, that’s when people smile. Their whole body language changes.” A full decade before Liza Minnelli and Hazell Dean each scored their own hits with the song, Elliman brought “Love Pains” to #34 on the Hot 100, her last Top 40 hit of the decade.

RSO finally released Yvonne in the fall of 1979, grouping Barri’s three cuts together with the tracks Appère had produced a year earlier. Grazing the Billboard 200 at #174, Yvonne clearly didn’t receive the same level of promotional support as Night Flight, foretelling the end of Elliman’s tenure with RSO. “Night Flight and Yvonne didn’t sell,” she says. “That’s why I got dropped from RSO. Through the years, I’ve had to pay the cost of those albums through my royalties. Whenever somebody drops you from a label, it’s like a rejection. In my heart of hearts, I don’t think I was really that upset because maybe I was ready to move on to something else.”

Meanwhile, Shep Gordon found ways to keep Elliman in the public eye, even as her time with RSO drew to a close. In September 1979, PBS broadcast Elliman and Teddy Pendergrass’ concert at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles as part of Summerfest ’79. Gordon’s Alive Enterprises also produced Yvonne Elliman In Concert (1979), a full-length video that Billboard described as “the first videocassette manufactured under a fully executed contract by the American Federation of Musicians” (22 December 1979). “If it came out, it was in a very limited form,” says Gordon. “It was before MTV. We used it as a press thing to get attention for the artists.”

A year later, Elliman and Stephen Bishop recorded the classic Ashford & Simpson tune “Your Precious Love” for the Roadie (1980) soundtrack produced by Gordon’s company and Steve Wax Enterprises. It would be one of the last songs Yvonne Elliman recorded for more than 20 years.

Retreat and Renewal